Can Russia afford to be a great power?

While Russia wants to be recognised as a great power, and has sufficient economic power and potential to encourage it to behave accordingly, there are economic limits to its behaviour.

- Russia wants to behave as a great power, but under its current leadership it is sensitive to its economic capacity to do so.

- There are serious restraints, resistant to policy action, that limit its economic capacity.

- While the West has no determining influence over the Russian economy, it does have the capacity to raise the economic cost to Russia of inappropriate great power behaviour, and should do so.

Executive Summary

Russia wants to be recognised as a great power, and has sufficient economic power and potential to encourage it to behave accordingly. However, under its current leadership it recognises that there are economic limits to its behaviour. There is a consistent commitment to budget discipline and a measured allocation of resources among key claimants — the social and development sectors, as well as defence and security. That limits the allocation of resources to power projection, particularly of the hard variety, even if such allocation is at a level high enough to cause considerable discomfort in the West.

The Russian economy is subject to particular pressures: stagnant growth even before the 2014 fall in oil prices, and the budgetary and investment challenges of lower oil prices and sanctions. The commitment to budget discipline and a measured allocation of resources has been maintained. However, there has also been a major rhetorical and policy shift towards a more ‘securitised’ economy, including import substitution-led industry policy. There are major features of the Russian environment which threaten the success of such a policy shift, but which are highly resistant to policy action. They include much discussed institutional weaknesses, as well as issues of remoteness, climate, market size, and industrial location that make it difficult for Russian industry to be globally competitive. The West has no determining influence over the Russian economy. But it is able to raise the costs of great power behaviour, through reducing access to investment and technology, and should do so.

Introduction

In recent years, Russia has re-entered the geostrategic calculations of the West in ways reminiscent of the Cold War. Russia’s actions in Ukraine and Syria and the rhetoric of President Vladimir Putin, among other things, are symptomatic of this renewed assertiveness, but they do not explain it. There is no question that much of this assertiveness can be attributed to the personality of Putin himself as well as the Russian nationalism that the president has both fed and fed off. Nevertheless, it does not seem coincidental that Russia reasserted itself during a period of rapid economic growth in the first 15 years of Putin’s rule. This raises the question of whether Russia can afford to be the great power it clearly aspires to be.

Russia’s desire to be a great power poses a challenge to Western policymakers. There is, however, a spectrum of ‘greatness’ along which Russia can place itself. Although Russia will attempt to situate itself as far along the spectrum as it can afford, at present it is placed quite modestly. Its economic autonomy is tenuous, in terms of policy commitment and reality. Its control over its claimed sphere of influence is limited, certainly when compared to Soviet and even Tsarist times. And its activities in the far abroad are limited in scope and nature.

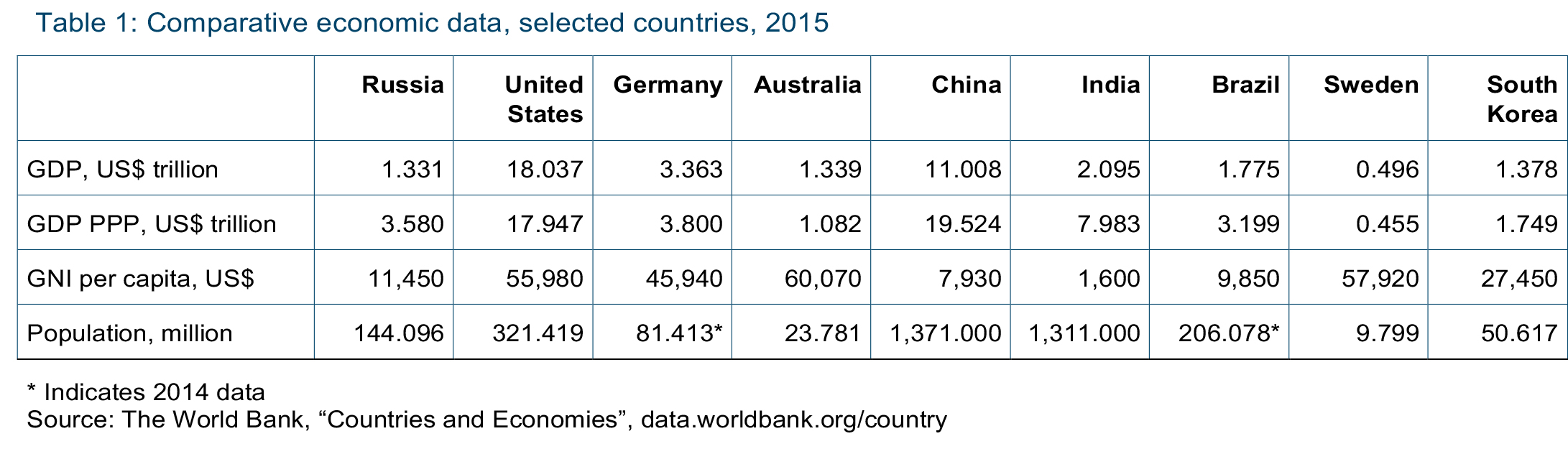

Russia’s position along the spectrum of greatness is predominantly a matter of economic capacity. Its economy is not without heft, ranking No 6 in the world by size (2015 GDP, purchasing power parity).[1] Given that the prosperity of the population is seen by Russia as part of its great power status, income is as important as the total size of the economy. However, Russia is still classified by the World Bank as an upper middle-income country, a category that contains 56 countries ranging from Albania to Venezuela.[2] As this Analysis will show, Russia’s ability to escape this category is likely to be limited. A mismatch between expectations and economic capacity presents Western policymakers concerned by recent Russian behaviour with some interesting policy choices.

What kind of power?

Before considering whether Russia can afford to be a great power it is important to specify what being a great power means in Russian terms. Five features of Russian great power status can be identified.

First, that Russia should be an economically autonomous actor on the world stage. Russia’s economic engagement with the world should be on terms that at best it controls and at worst it has veto rights over. If that is unattainable, withdrawal from economic engagement should be an option.

Second, that Russia should be able to ensure the geostrategic security of the nation by maintaining its capacity to match or better the nuclear capacity of the United States and other nuclear powers.

Third, that Russia should have the ability to ‘show the flag’ globally and intervene militarily well beyond its borders in at least one theatre, and to have a ‘hybrid’ presence more widely.

Fourth, that Russia should have an unrestrained capacity to assert itself in its immediate sphere of influence.[3]

Finally, that Russia should have the ability to ensure stability at home, including through a population sufficiently content with its material circumstances as not to threaten that stability. This is important for Putin, not just because it makes his own position more secure but because it makes a statement about Russia’s status in the world. It is often claimed that as the Russian economy has faltered, Putin’s reliance on economic prosperity as the basis of popular contentment has been replaced, at least partially, by patriotic fervour.[4] It is unlikely that Putin is entirely confident in such a shift, and so achieving economic prosperity will remain a priority for the regime.

Limited potential

At the Sochi Investment Forum in September 2014, Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev outlined a long list of failed Western attempts to put economic pressure on Russia, noting:

“If history is any guide, all such attempts to pressure Russia turn out to be ineffectual. It is clear that economic intimidation is not the way to deal with our country, as with any other country. Russia is the biggest country in the world in terms of land surface, with a population of almost 150 million people. We are a nuclear power that has abundant natural reserves, and is [sic] a major market of goods, services and investments.”[5]

It is questionable whether the strengths claimed by Medvedev in fact guarantee Russia the economic autonomy or might of a great power. There are a number of reasons why that might be, but four particularly persistent factors are often advanced to explain previous Russian failures to meet its potential.

The first relates to the geographic limits of Russia’s economic potential. Russia’s climate and topographical features mean that Russia will always struggle to be competitive against nations with more temperate climates. These geographical disadvantages mean that it adopts authoritarian and highly centralised approaches to government in order to make the best use of its resources.[6] These approaches, while providing some capacity to mobilise resources, ultimately are not conducive to flexible and responsive policymaking.

Further, the ideological and security imperatives of settling the whole land mass, particularly under Stalin, led to uncompetitive industrial enterprises being located in remote and inhospitable regions.[7] Even in more market-oriented post-Soviet circumstances, the legacy effects of those Soviet-era location decisions still exist. They are evident in an exchange between President Putin and Deputy Prime Minister Arkady Dvorkovich at the Council for Strategic Development and Priority Projects meeting in November 2016. When Dvorkovich stated that the locational mistakes of the Soviet era had to be avoided by ensuring that new export-oriented manufacturing capacity be located close to ports, Putin interjected that they could be located close to railways. Dvorkovich cautiously pointed out that hauling goods thousands of kilometres by rail was commercially unviable.[8] The continuing security imperative can be seen in the recent policy focus on developing the Russian Far East in a way that jobs will be created and the region will be a more pleasant and convenient place to live, and in the fear that if the region is not developed to the extent needed to support a far larger population it will be susceptible to takeover by the Chinese.[9]

Demography is a second factor often said to be limiting Russia’s economic potential. While the security-related urge to settle remote territory is one aspect of Russia’s demographic concerns, the size of the population as a whole is another. At 144 million people, Russia’s population is not insignificant (see Table 1 for comparative data). But neither is it a big economy simply by force of numbers, as can be said of China and India. While Russia represents an attractive market when circumstances are right, at the same time it is not a large market and can be ignored by global providers of goods, services, and investment when circumstances are not right.

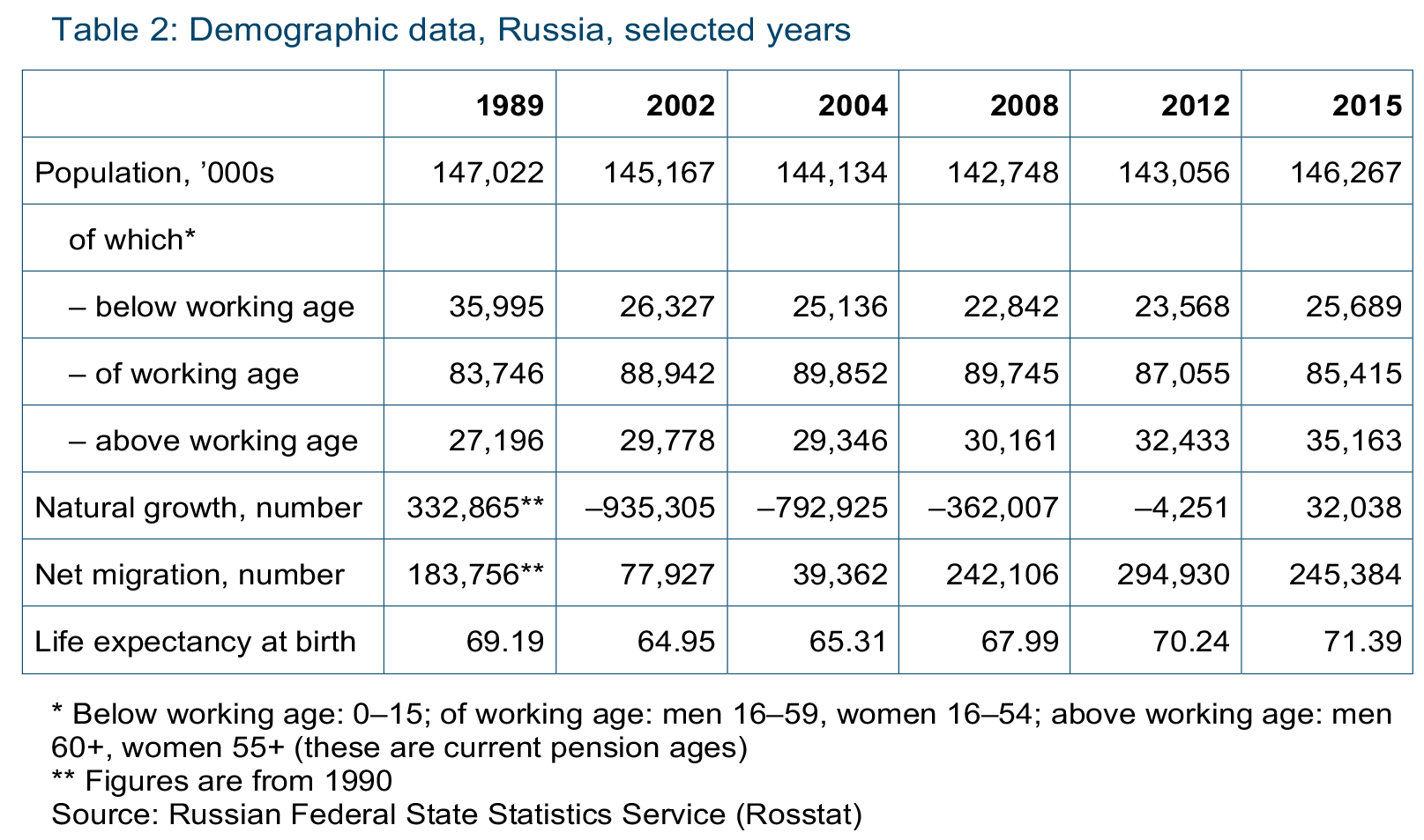

In addition, Russia’s demographic outlook is not positive. Table 2 shows recent increases in the birth rate, likely a result of generally improving socio-economic conditions as well as specific government policies, such as the Maternity Capital payment (a cash benefit received on the birth of a second and subsequent children). However, working-age population is still a problem, with numbers falling and little prospect of improvement. The Ministry of Economic Development’s economic forecast to 2035 predicts stable workforce numbers; however, this is highly optimistic, not least due to the high levels of immigration included in the prediction.[10]

A third factor is the resource curse. The resources sector crowds out other forms of economic activity, both by driving up costs domestically but also through high levels of foreign currency inflows pushing up the real value of the currency and rendering domestic economic activity uncompetitive. While there is debate in the academic literature as to whether Russia suffers from economic distortions known as Dutch disease,[11] there are sufficient signs to suggest that it suffers from something like it. The ruble, between spectacular bouts of devaluation, generally appreciates in real terms, while import levels are high and non-resource industries struggle. Exchange rate issues feature prominently in any economic debate in Russia.

Finally, various cultural explanations have been put forward to explain Russian nation-building failures. The most relevant economically include: a great power complex, producing a need to engage in great power behaviour even if it cannot afford it; an unwillingness to ‘obey the rules’, meaning widespread corruption, cronyism, and a chronic failure to develop stable institutions; a view of the world in which a strong leader at the head of an overconfident state is more attractive than private entrepreneurship and individual human rights; and, as can be sensed in the Medvedev quote above, a ‘cultural’ belief that because it is so big and so rich in resources Russia cannot fail to be a great power.

For Russian policymakers dealing with the economy on a day-to-day basis, broad geographical and ‘cultural’ issues take a back seat to getting the economic settings — macroeconomic, budgetary, and more ambiguously institutional — right. In their eyes, with the requisite technical expertise and a rational policy process that can be achieved. This Analysis argues that while it is vital to get economic policy settings right, that in itself is not sufficient to allow Russia to maximise its economic potential. No matter how competently settings are dealt with, the broader issues outlined above will continue to have an effect.

Current and future prospects

The Russian economy has taken a battering in recent years, after strong growth through most of the first decade of the century (with much dispute as to how much of that can be put down to a solid base laid in the 1990s, the devaluation effects of the 1998 financial crisis, Putin’s good policies, or rising oil prices). Throughout these good years, there were concerns about how long growth could be sustained, given Russia’s excessive reliance on energy exports and therefore oil prices. Russia was not attracting the private investment it needed, either from abroad or domestically, at least partly because of a lack of structural reform. An endless debate went on among economic experts and policymakers as to what should be done to attract investment.

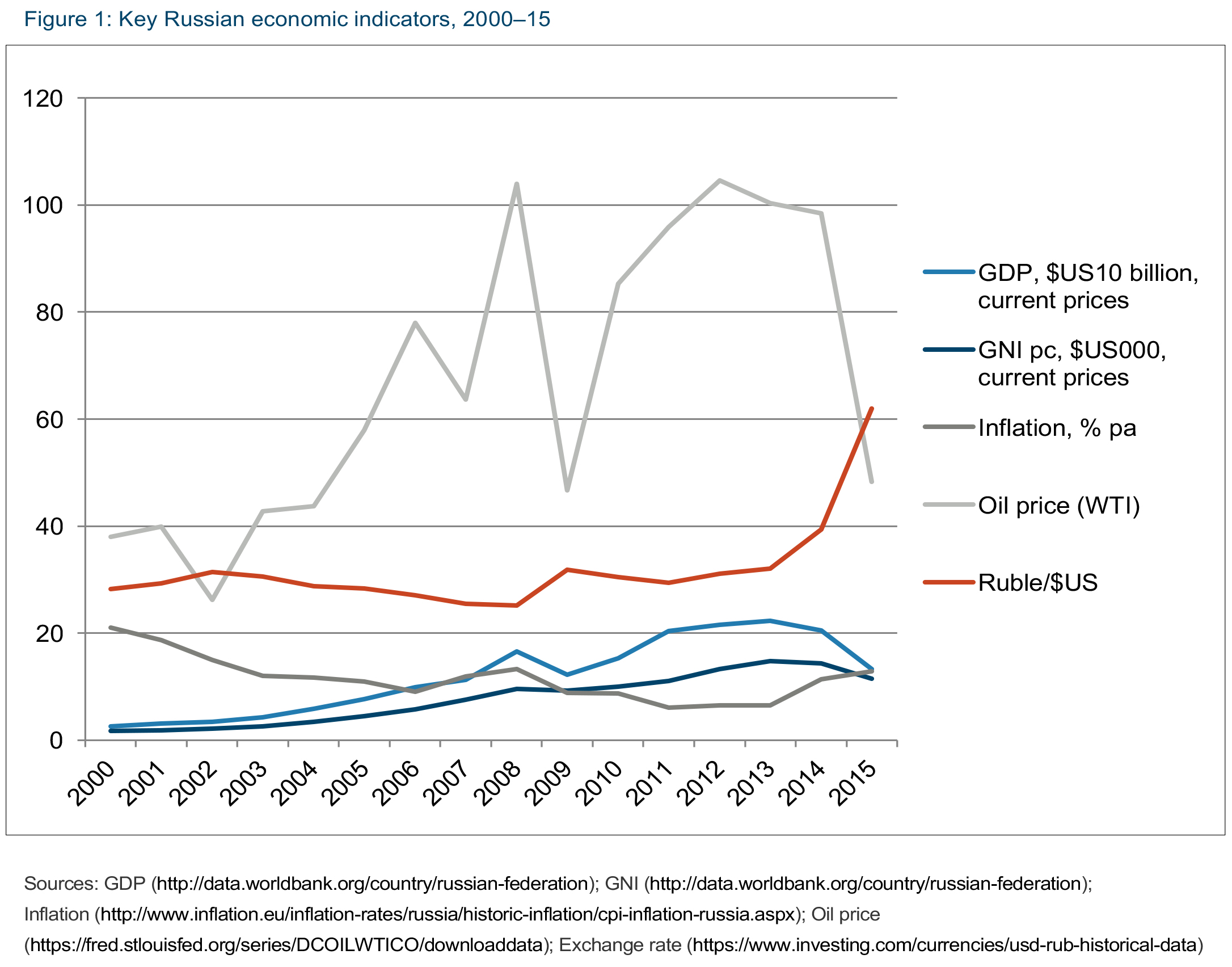

The debate was put aside when the global financial crisis hit. While it affected the Russian economy badly, the ruling elite considers that it handled the crisis well, with targeted relief for corporations with debt-related problems. There were signs of a relatively swift recovery. However, the economic recovery was anaemic, which led to anguished debate over how to get back to the old dynamism. Then in 2014 came the sanctions imposed by Western nations following the annexation of Crimea, separatist activities in east Ukraine, and the shooting down of Malaysian Airlines Flight MH17. Sanctions included limitations on the travel of selected individuals as well as investment in and technology transfer to a range of strategically important enterprises. They were followed by counter-sanctions imposed by the Russians, mainly on imports of agricultural products from the countries that were sanctioning Russia. Next came the collapse in oil prices late in 2014. All of these factors contributed to a sharp devaluation of the ruble, a serious burst of inflation, major declines in real incomes and economic growth, and a real sense of economic crisis (Figure 1).

Nevertheless, the economy showed resilience. As Prime Minister Medvedev noted in April 2016:

“They repeatedly predicted catastrophic consequences for us, saying that our economy will be left ‘in tatters.’ It is not in tatters. There are difficulties, but Russia’s current economic and financial situation is much better than it was in other periods in our history.”[12]

Declines in output across many sectors of the Russian economy have bottomed out, with recent statistical revisions suggesting that the decline was never as severe as first stated. The ruble has stabilised and is indeed appreciating, to the consternation of many policymakers. Inflation is approaching record lows. Capital outflows are well down and there is more money coming into the banking sector than flowing out.

The budget deficit for 2016 was set at what was seen as a manageable 3 per cent of GDP, and was allowed, with a fair degree of equanimity, to come in at an actual 3.56 per cent. To get to that figure, however, required substantial cuts across all budgetary categories (with defence least affected); the transfer yet again of individual pension contributions into a presidential reserve rather than individual accounts (with a considerable portion used to pay off defence industry debts); the partial indexation of pensions; an increased tax take from the oil sector, despite earlier promises of a tax moratorium until at least 2018; and the dramatic last-minute sale of 19.5 per cent of the state-owned oil company Rosneft for around US$11 billion.

The Russian economy might not be in tatters, but neither is it healthy. The fiscal outlook remains tight, even in noting that current budget planning is based on a perhaps conservative oil price of US$40 a barrel. Budget drafts see deficits continuing, albeit at a reduced level: 3 per cent in 2017, 2 per cent in 2018, and 1 per cent in 2019. There are also continuing cuts to expenditure, which is set to fall to 16.2 per cent of GDP by 2019 down from 19.8 per cent in 2016. And the Reserve Fund is to be exhausted by the end of 2017, with major inroads being made into its sister National Development Fund.[13] The deficit is to be financed primarily by domestic borrowing. In monetary terms, the central bank is resolute in holding interest rates well above the rate of inflation.

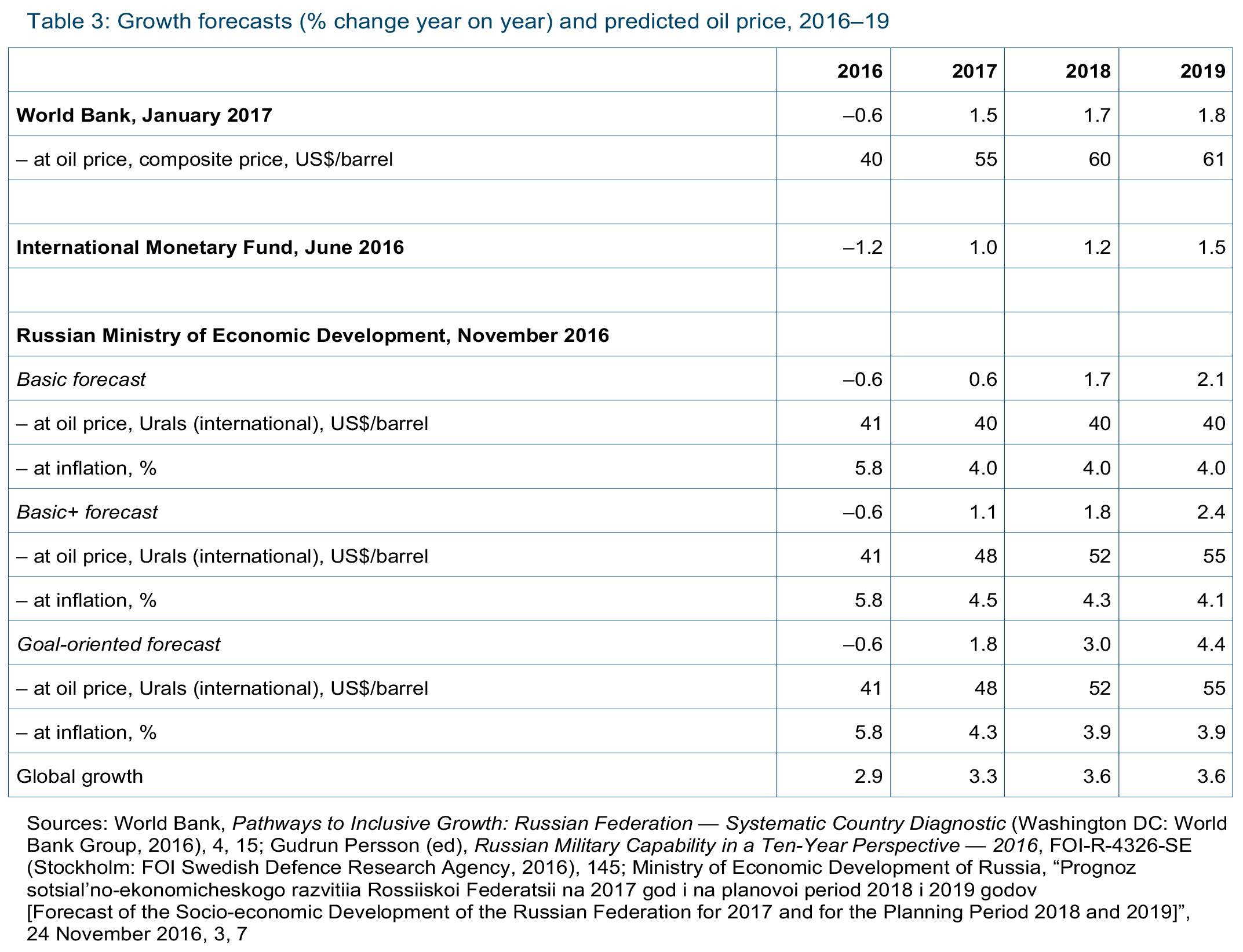

In that context, the main policy focus is on stimulating growth. The Russian economist Kirill Rogov notes that over the eight years from 2008 to 2016 Russian GDP grew by 1.5 per cent. During that same period, the world economy grew by 18 per cent, Kazakhstan by 42 per cent, Turkey by 32 per cent, and Brazil by 17 per cent.[14] The debate on how growth is best achieved is a highly charged one, not least because Putin is committed to a growth rate that is unlikely to be achieved according to most forecasts. He wants growth above the global average, with the ideal figure being 4 per cent. Various growth forecasts are shown in Table 3. The ministry’s ‘goal-oriented’ forecast is the only one that achieves 4 per cent by 2019, thereby surpassing the Ministry of Economic Development’s forecast of 3.6 per cent global growth in that year.[15] Goal-oriented forecasts are presented as achievable only if optimistic starting assumptions are fully met. Those assumptions include institutional reforms that many consider unrealistic. While Putin’s desired growth target is in the goal-oriented forecast, that forecast was not used to draw up the 2017–19 budget. Instead, the Basic+ forecast was used, with a predicted growth rate of 2.4 per cent by 2019. Both forecasts assume an oil price in 2019 of US$55 a barrel, which at the time of writing could not be described as extravagant. (Note that the World Bank predicts a lower growth rate at a slightly higher oil price.)

Various policy approaches have been put forward to achieve the growth target: macroeconomic stability, ‘modernisation’, monetary emission, and sectoral ‘locomotives’. They are outlined here in a simplified form.

Macroeconomic stability: Key proponents include the Ministry of Finance, former Finance Minister Alexei Kudrin, and Central Bank Chair Elvira Nabiullina. Growth and diversification will come as market forces respond with strong demand and investment to low inflation and consequent low interest rates. Low inflation requires a balanced non-energy budget. How oil and gas revenues should be handled, so as to allow both inflation and exchange rate goals to be met, is a complex matter of debate between the Ministry of Finance and the central bank.

‘Modernisation’: Key proponents include the Ministry of Economic Development and presidential adviser Andrei Belousov. The ‘modernisers’ are sensitive to macroeconomic stability but believe that room must be found for state investment in infrastructure and high-tech projects that are essential for a diversified economy, but which are too big or generate insufficient returns for private investors. Dmitry Medvedev has been a keen advocate of such an approach, particularly while he was president from 2008 to 2012.

Monetary emission: Key proponents include academic economists such as Sergei Glaz’ev and the influential economic group known as the Stolypin Club. In this view, there should be a bold approach to printing money to finance investment, both in high-tech sectors and established manufacturing. Extensive underutilised capacity and rapid increases in output mean that inflation would not become a major issue.

Sectoral ‘locomotives’: Key proponents include major figures in the relevant sectors, such as the head of Rosneft, Igor Sechin, in the energy sector, and Deputy Prime Minister Dmitrii Rogozin, who is in charge of the defence industry sector. Two ‘locomotives’ are seen by their advocates as driving the Russian economy. The first is the energy locomotive, Putin’s long-held view that Russia’s economic strength is derived from oil and gas. However, even he has been forced to admit that the model has been compromised by the lack of growth after the global financial crisis even when oil prices were high, and the fall in oil prices and doubts about their recovery (although whether he has truly given it up is questionable). The second is the defence industry, which Putin speaks of as the new locomotive through its direct contribution to economic growth as well as technological spillovers into the civilian sector.

The proponents of all approaches acknowledge the importance of ‘institutional reform’, from removing administrative and regulatory barriers to entrepreneurial activity and trade, through to dealing with corruption and ‘raiding’.[16]

It appears that ‘institutional’ issues will form the core of a major new reform program requested by Putin and currently being put together by former Minister of Finance Aleksei Kudrin, in a process in which the fiscal conservatives and the Stolypin Club are expected to work together. The program is due to appear in the near future, and will no doubt attract much attention when it does. It is highly unlikely that any proposals for institutional reform will be successfully implemented, and certainly not in time to deal with great power related funding issues to be faced in the 2017–19 budget.

Outlook for defence and social spending

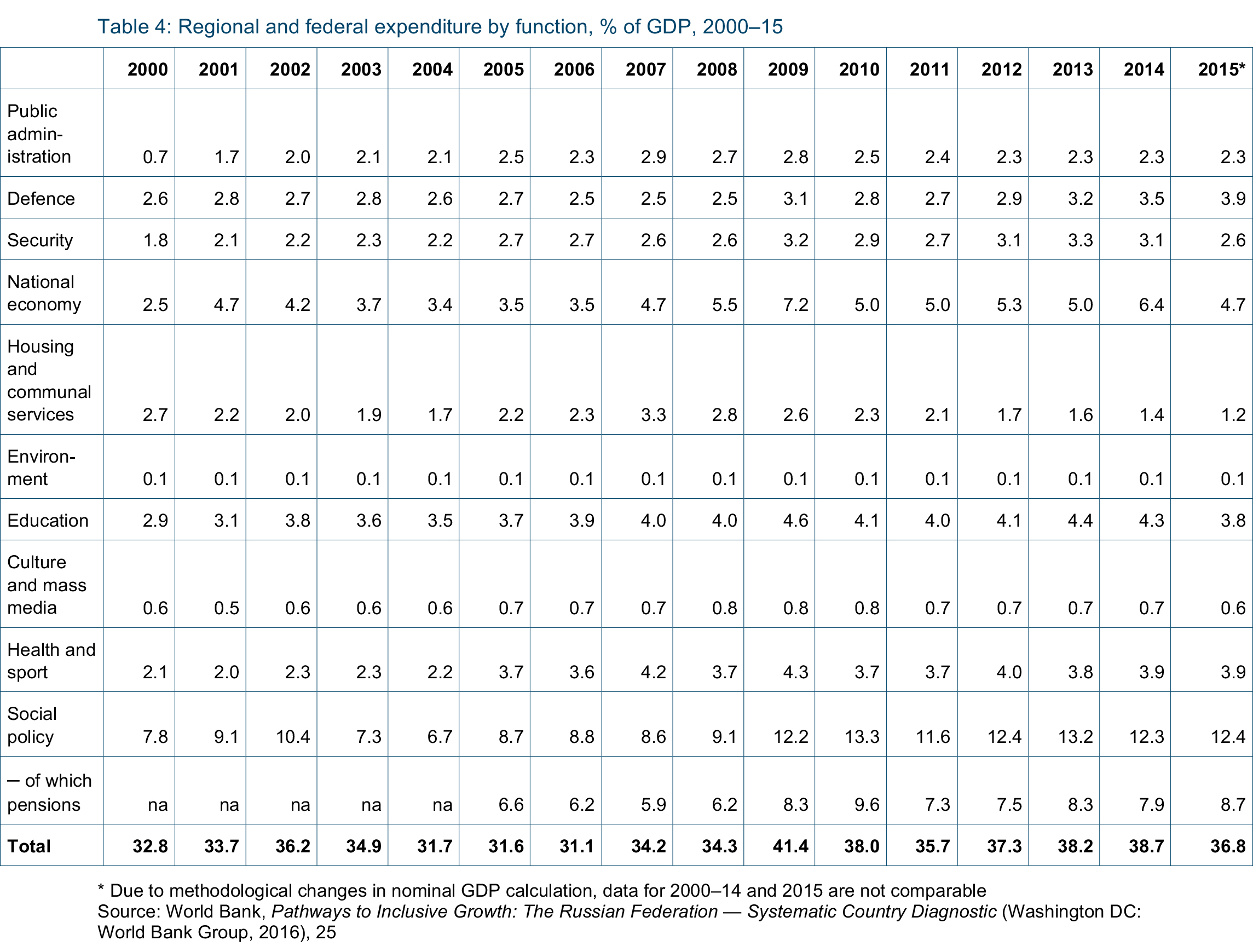

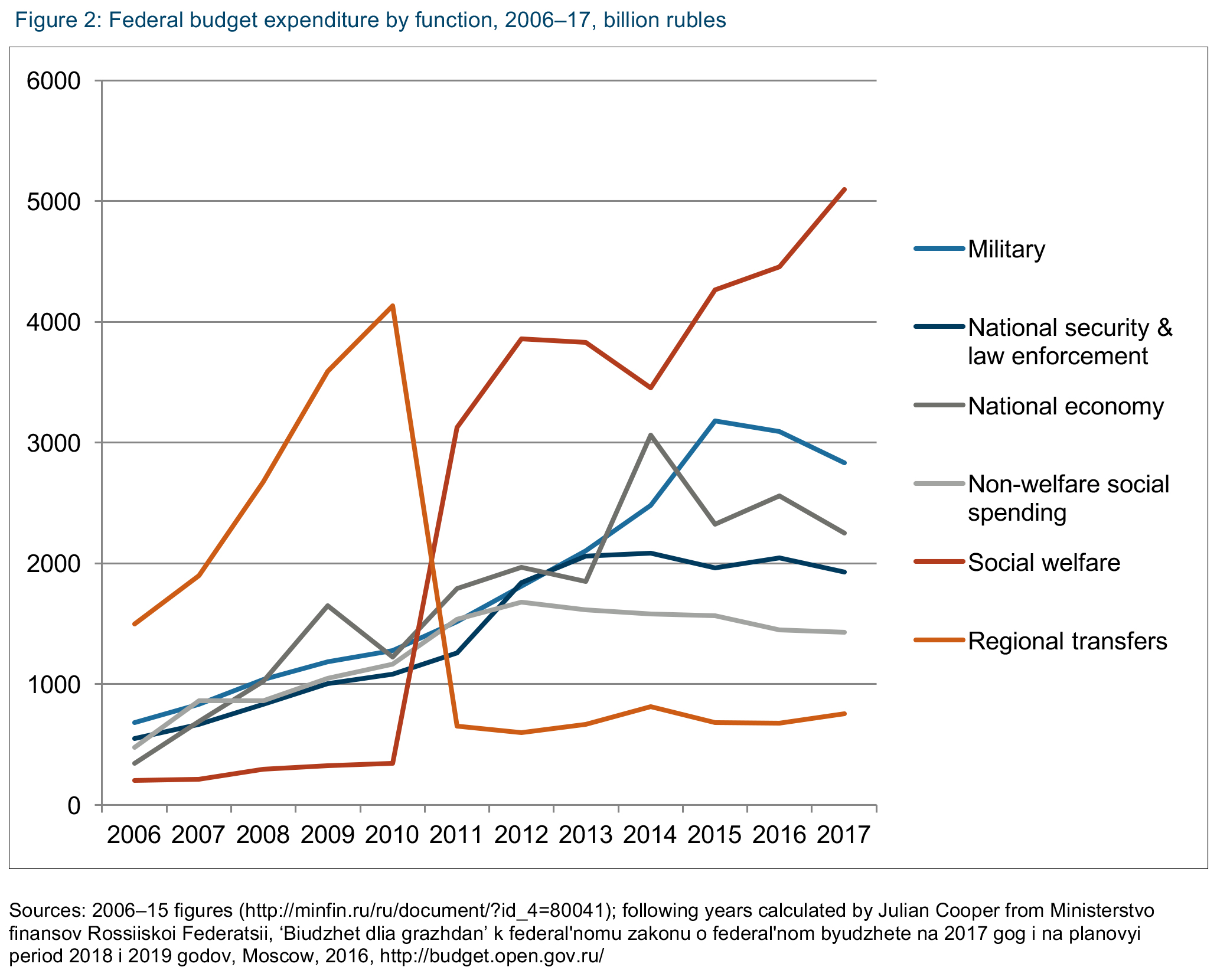

How in great power terms is Russia’s budget allocated? The foreign policy aspects of Russia’s great power aspirations lead one to expect considerable emphasis on force projection and therefore defence spending. But there is also the contented population component of Russia’s definition of a great power, with its attendant social spending. Table 4 shows the breakdown of general budget expenditures (i.e. federal and regional expenditures) by function, as a percentage of GDP from 2000 to 2015. Figure 2 shows the breakdown of federal expenditures only, by aggregated function from 2006 to 2017.

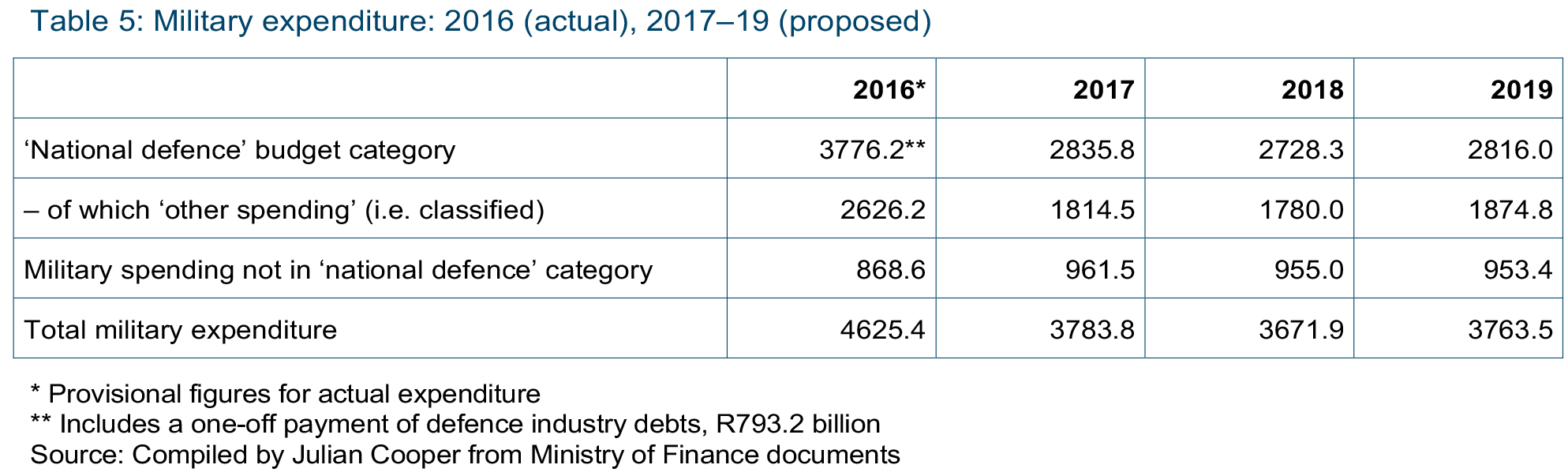

The defence budget represented around 82 per cent of total military expenditure in the 2016 budget.[17] Military expenditure has increased substantially, particularly since the war with Georgia in 2008, which revealed considerable shortcomings in military performance after a couple of decades of neglect. A large part of the increase has gone towards a weapons modernisation program. While in 2015 Russia’s military expenditure of US$91 billion (in 2014 dollars; in 2015 dollars $66.4 billion) was well below the Unites States total of $595 billion and China’s $214 billion, as a share of GDP Russia’s 5.4 per cent outstripped the other two — the United States and China at 3.3 per cent and 2 per cent, respectively — as well as India at 2.3 per cent, the European Union at 1.5 per cent, and Japan at 1 per cent.[18] While there is an element of catch-up after a period of neglect, these are signs of a middle-income country striving to be a great power.

While defence expenditure was least affected by the most recent cuts, draft budget figures for 2017–19 show a significant decline in defence spending (see Table 5). This is based on the expectation that the rearmament program, the major beneficiary of the big increases in military expenditure in recent years, will have been largely completed. That expectation is shared by Putin and accepted by defence sector leaders in public statements and quite likely to become reality.[19] Nevertheless, a few questions can be asked: will armament modernisation targets be reached, and if not will the military lobby successfully to maintain expenditure until they are? Will the failure of the program to develop new weapon systems in some key areas, as distinct from upgrading older systems, produce pressure to maintain expenditure? Will the proposed solution to the problem of what to do with defence industry capacity once military orders decline — to transfer them to high-tech civilian production — succeed, and if not will there be pressure to maintain defence orders simply to keep capacity operational?

If military spending fails to fall as much as predicted in the budget, this will have implications for social spending. There have been significant increases in social spending in recent years. Still, allocations as a percentage of GDP remain below developed world levels: in 2013 total health spending was 3.2 per cent, against an average 6.5 per cent for OECD countries; in 2012 the figures for education were 4 per cent and 5.3 per cent, respectively.[20] The division of social spending into ‘productive’ (expenditure on human capital) and ‘non-productive’ (expenditure on welfare) items has become a major political issue. Fiscal conservatives are prepared to consider protecting productive spending if more attention is devoted to reducing inefficiencies in welfare expenditure, including through stricter means testing.

Social welfare has, however, become an ever more important contributor to the economic security of the poorer sections of Russian society. This is an issue of great political sensitivity, since it is generally considered that the recipients of non-productive social spending are the core of Putin’s constituency (as well as being the most vulnerable section of the population). So far the only social spending changes relate to means testing and eligibility requirements for social welfare payments — that is, measures that could claim to contain an element of social justice. But one, perhaps two, costly commitments remain. The first is pensions. Under the circumstances of the 2014 crisis, Putin accepted the need for the partial indexation of pensions for two years. Full indexation is included in the 2017 budget, although only for non-working pensioners, a sign of means testing in operation. But despite constant efforts by fiscal conservatives, raising the pension age remains firmly off the agenda.

The second commitment — pay increases for state sector workers called for in the May decrees[21] — is still pursued with vigour by Putin, despite the strain it puts on federal and regional budgets. It could, of course, be argued that state sector salaries (for teachers, doctors and scientists, for example) are an investment in the nation’s human capital and therefore should not be counted as ‘non-productive’ social spending.

The government’s rhetoric is that there is clear room for a reduction in the defence budget and that there are social obligations which will be met no matter what the cost. While its policy action during the 2014 crisis has not matched the rhetoric — defence has suffered fewer cuts than social spending — action could well more closely match rhetoric in the future, particularly in the run-up to the 2018 presidential election. But if military spending cannot be contained, then social spending must suffer, with perhaps the pension age rising after 2018. The most dramatic expression of this would be if social spending suffered to the degree that it destabilised the regime. However, the pressure to reduce social spending is unlikely to be that great in the medium term.

Investment

There is a third category of spending in Russia’s budget that is also relevant to its great power ambitions: the so-called ‘national economy’ category. This is in broad terms the ‘investment’ category and is often described as ‘residual’, funded with what is left after other claimants have been satisfied and therefore most likely to suffer when budget conditions are tight. The data does not totally bear that out, with big increases in this category during the global financial crisis and again in 2014 (see Table 4).

The national economy category in practice serves two and increasingly three goals. The first is investment in infrastructure and growth-inducing measures; the second in what is in effect social welfare spending, in the form of subsidies for struggling but socially sensitive industries; and the third in what could be called ‘securitised’ expenditure, to cover cuts in the defence category or to support industries on national security grounds. The second goal is resilient to major cuts, and the third is arguably increasingly important. That could well leave the first goal as a particularly vulnerable residual when the category’s overall allocation is falling.

The implications of cuts in investment in infrastructure and growth-inducing measures could be reduced, if private investment looked likely to take up the slack, but there are considerable doubts in that respect. Currently Russian lending institutions have plenty of liquidity, but prefer central bank deposits to investment opportunities. If in the future the budget deficit is to be funded through domestic borrowing, real economy investments are even more likely to be crowded out.

All the growth models outlined above identify the poor investment climate as a drag on investment, and therefore call for so-called ‘institutional reform’ as an important reform measure. However, given that institutional weaknesses of the Russian polity and economy — corruption, a rapacious bureaucracy, an ineffective legal system — remain as defining characteristics of the Russian system of government without which it could not exist, reforms are unlikely to be made.

One can see a scenario in which available state investment funds are rigorously spent in categories that contribute to Russia’s great power ambitions: force projection; the level of social welfare spending needed to keep Putin’s constituency quiescent; and ‘securitised’ investment, leaving little for productive investment in non-military areas. This raises the question of whether Russia might be heading down a similar ruinous path to the one that contributed to the Soviet Union’s demise.

'Securitised' economy

It could be argued that the Soviet Union collapsed because its whole economy was ‘securitised’. That does not just mean that massive funding and material resources were devoted to military ends, although that was certainly the case. It refers to the way that the whole of society was to be mobilised against foreign foes, producing an economic policy orientation towards self-reliance limited only by costly engagement with a narrow outside world of colonies and clients. Over time it was so inefficient that it became impossible to maintain even the Soviet Union’s not particularly generous ‘social contract’, so often characterised in the popular saying ‘we pretend to work and they pretend to pay us’. Eventually the securitised economy took so much that the state was unable even to pretend to pay the population (in the form of providing goods to buy with the money they received). The population stopped pretending to work, leading to economic collapse.

Currently it is hard to see things turning out that way in Russia, even given persistent problems of low labour productivity. The Russian economy today is not the totally state-owned and centrally planned economy of Soviet times. One can be well rewarded for working well, and dismissed for not doing so, in which circumstances it is difficult to see how a mass, spontaneous sit-down strike of a late-Soviet variety could occur. While that could well provide Russia with greater resilience than the former Soviet Union had, it is nevertheless worth looking at the possible effects of the great power goal of autonomy, specifically in terms of self-reliance and engagement with if not colonies and clients then at least a small outside world of non-commercial customers.

Moscow’s policy of import substitution was only fitfully pursued before sanctions gave it a major boost. It is unclear how far towards self-reliance import substitution is intended to go. The regime’s hard-core rhetoric is matched by assurances that it means no more than reasonable localisation — that is, requiring foreign firms wanting to sell into the Russian market to produce both the end product and its components in Russia — and not Russia’s withdrawal from the global economy. Russia does not have a centrally planned economy, all components of which can be dragged towards self-reliance. There is a ‘liberal’ policy community, a private sector, and even state corporations that are more market-oriented than their Soviet forebears, all arguably able to resist — politically and commercially — self-reliance, and thereby offer the capacity for economic growth and development within an integrated economy.

Nevertheless, the extent to which these actors are able to offset the pressures from the proponents of self-reliance is difficult to say. Those pressures include a powerful ‘national security’ lobby, operating at the very top of the system and possibly including Putin himself, through to bureaucratic and corporate actors that see themselves as benefitting from a securitised economy, such as those that promote import substitution on the grounds that struggling but strategic industries must be supported both on economic autonomy and social welfare grounds. A small domestic market for the output of these industries creates pressure to seek external markets on non-commercial terms.

The policy successes of the proponents of a securitised economy include: a major import substitution program, containing not just state funding but also central control of purchasing and production that is reminiscent of the Soviet central planning agency, Gosplan, and enthusiastically promoted by the Ministry of Industry and Trade; new subsidies for industrial projects combining import substitution and industry policy goals, with the beneficiaries being the car and truck industry, aviation, shipbuilding, agriculture and agricultural machinery, and even light industry; and the promotion of manufacturing exports on non-commercial terms.

It is too early to conclude, however, whether these developments suggest that Russia is on the slippery slope towards a securitised economy. There is much opposition to the Ministry of Industry and Trade’s efforts to turn itself into the new Gosplan, not least from powerful state corporations that fear not just bureaucratic supervision of their activities but also that import substitution will leave them with either no key inputs or inferior and expensive domestically produced ones. The subsidies, while not insignificant, are not enormous, and there can be big differences between budget allocations and money actually received and spent.

The armaments sector represents an interesting case study of state subsidisation. Some of the Soviet Union’s genuine strength in that area has been maintained, including an impressive export market. But this should be seen in the context of persistent indebtedness,[22] unverified claims of severe price inflation within the sector, the regular arrest of its managers for corruption, and its apparent difficulty building new weapons as distinct from modernising Soviet-era models. This relatively successful sector might therefore be an exemplar of Russian industry more broadly: a capacity to manufacture complex modern products, but not of the highest quality or level of innovation and at high cost with persistently negative returns on capital.

What of the turn to non-commercial export markets? Policymakers have placed great emphasis on various export promotion agencies, most of which differ little from such agencies around the world. Is there any reason to believe that they will be the instruments of a Soviet-style provision of non-commercial, indeed non-repayable, credits to client states?[23] There are signs this is happening. Take as an example the sale of locomotives to Cuba announced at the 2016 Sochi Investment Forum. Renewing a Soviet-era relationship, the deal — worth over 168 million euros — is funded by the Russian Export-Import Bank and insured by a state-owned insurance agency. The Ministry of Industry and Trade compensates the bank for the gap between the interest rate charged and market rates and the same ministry is investigating a subsidy for the cost of transporting the locomotives to Cuba. While the producer is privately owned, nevertheless it is hard to see the deal not costing the state money.

While evidence of ‘securitised’ behaviour, which is likely to earn Russia a negative commercial return, can be found, it is not yet strong enough to declare it to be a system-wide phenomenon, although it might be argued that the logic of Russia’s great power aspirations suggests it is a constant danger.

Whether Russia succumbs to the danger depends on whether it is funded, which comes back to the issue of fiscal rectitude. So far Putin’s fiscal discipline has been impressive. However, the demands on the budget are relentless at a time when macroeconomic circumstances might encourage giving ground. Through 2016, inflation roughly halved. Although the fall in inflation is partly an artefact of the very high spike following the rapid devaluation of the ruble in 2014, a keen lobbyist could readily make the case that there is a demand deficit that recommends some Russian quantitative easing. And this in circumstances in which oil prices are higher than written into budget planning, promising a budget windfall. As always, when a windfall appears on the horizon, a frenzied policy debate ensues on how to spend it. The Ministry of Finance wants it to go into reserves and to have no effect on expenditure limits. The ministry’s many opponents want it to be used to increase expenditure.

Although structures exist to allow the Ministry of Finance’s opponents, including the monetary emission lobby, to express their views, both history and the apparent line-up of forces among Putin’s economic advisers suggest that he is unlikely to yield to temptation. That could well save Russia from rapid inflation and all that would follow, but it also means a tight budget that limits expenditure on great power goals.

Conclusion

Russia will be as much a great power as it feels it can afford. The question is, therefore, how much can it afford? Can it even afford its current relatively modest level of great power behaviour?

What answers does the 2017–19 budget cycle offer? Leave aside for the moment that the budget is written with oil at US$40 a barrel.[24] As the budget is written, Putin’s goal of growth above the global average by 2019 is unattainable, meaning that it sees Russia slipping down the global economic league table, at the same time as winding back to some degree the welfare state, running down reserves, and undertaking new borrowing. The budget also contains signs of securitisation: blurring the boundaries between the civilian and defence economies, including extending the typical features of securitisation, namely self-sufficiency and non-commercial external relationships, to the civilian sector.

How much difference will it make if oil prices hold above US$40 a barrel? That will help the fiscal balance of the budget: slower depletion of reserves, less borrowing, a bit more spending. But will it help achieve Putin’s growth target, remembering that growth was slowing when oil was over US$100 a barrel? The most commonly identified obstacle to sustained growth is institutional, with its considerable ‘cultural’ component. The main issues are corruption, rapacious bureaucracy, and an inadequate legal system. It is hard to see corruption in all its manifestations being rooted out, but that is not necessarily an insurmountable barrier to investment and growth, if the returns net of corruption costs are attractive. A greater problem is the threat to property rights inherent in a ‘raiding’ bureaucracy and inadequate legal system.

It is conceivable that a ruthlessly committed government might resolve these matters, but would that be enough for Russia to achieve the growth rates it seeks? Two key reasons suggest not.

First, as already noted, the size of Russia’s market, which is closely linked to its demographic circumstances, is a limiting factor on investment. It can be seen in operation in current Russian efforts to diversify its economy. Industrial firms producing locally, whether they be domestically or foreign owned, have to export in order to reach economies of scale, with the car industry a clear example. The need to export is also a constant theme in import substitution discussions, and there is the consequent danger of sliding into Soviet-style non-commercial export activity.

Second, while the rigours of the post-Soviet market have produced some shake-up of the geographical location of economic activity and the population serving it, the evidence of a continuing legacy of major industrial activities located in remote and high-cost locations is strong. For understandable socio-political reasons, the current policy approach is to revitalise the legacy rather than remove it. ‘Territories of accelerated growth’, the latest approach to pushing growth through creating special conditions in strategically selected areas, are geographically scattered, with many in struggling one-company towns in remote locations. The ‘special economic zones’ that they have replaced as the preferred instrument, while not without such characteristics, were more concentrated in central urban conglomerations and are more high-tech oriented.

Russia’s current economic difficulties — a tight budget and low growth rate — could be seen as a consequence of low oil prices and institutional problems. Neither is easily resolvable. The former is not under Russia’s control; the latter is so daunting as to be barely so. But additional to those problems are other persistent, if not inherent, features of Russia’s economic environment: the size of its domestic market, which makes any effort to be self-reliant difficult; and geographical challenges, including locational decisions, that negatively affect Russia’s competitiveness.

These features are such that even if oil prices were to rise or if through institutional reform Russia were to succeed in attracting investment into non-resource sectors, it would still struggle to achieve the economic performance required to match its great power ambitions, even at its currently relatively modest position on the spectrum.

This is not to suggest that Russia should be written off or ignored. The economy is resilient, as it has demonstrated in weathering two recent crises. It is also of a size and with a resource endowment such as to encourage it to conceive of itself as a great power. In trying to turn conception into reality it can be aggressive and disruptive of the established world order.

That produces two challenges for the West. The first is to arrive at a realistic understanding of what it can do, either in the direction of providing the assistance that would allow the Russian economy to do better, or — more topically at the moment — in the direction of restricting economic performance and thereby Russia’s capacity to meet its great power ambitions.

In either direction the West’s capacity is limited. The West cannot turn Russia into a balanced and booming economy; nor can it undermine the economy and through it Russia’s political leadership to the point of irrelevance and collapse.

But even limited capacity is important. The West might not be able to transform the Russian economy, but within limits it can play a role in determining where Russia is on the great power spectrum. That leads to the second challenge: what should the West do? That depends on whether one believes Russian movement along the great power spectrum to be a good or a bad thing. If the West feels that Russia’s current place on the spectrum is cause for disquiet and any further movement along it undesirable, the capacity to increase the cost to Russia exists and should be used.

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges the data and comments provided by Julian Cooper, Silvana Malle, Andrew Monaghan and three reviewers.

Notes

[1] World Bank, “World Development Indicators Database”, 1 February 2017, http://databank.worldbank.org/data/download/GDP_PPP.pdf.

[2] World Bank, “World Bank Country and Lending Groups”, accessed 13 April 2017, https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups.

[3] There are questions regarding where the boundaries of the sphere of influence lie, in particular whether the Baltic states are within them. It would arguably be unwise to assume that the boundaries do not include all countries once within the Soviet Union and, if circumstances were particularly favourable, countries of the former Soviet bloc.

[4] Neil Robinson, “Russian Neo-patrimonialism and Putin’s ‘Cultural Turn’”, Europe-Asia Studies 69, Issue 2 (2017), 348–366.

[5] Dmitry Medvedev, Address at a plenary session at the International Investment Forum, Sochi, 19 September 2014, http://m.government.ru/en/news/14835/#medve_en.

[6] Allen C Lynch, “Roots of Russia’s Economic Dilemmas: Liberal Economics and Illiberal Geography”, Europe-Asia Studies 54, Issue 1 (2002), 31–49.

[7] Fiona Hill and Clifford Gaddy, The Siberian Curse: How Communist Planners Left Russia Out in the Cold (Washington DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2003).

[8] Meeting of Council for Strategic Development and Priority Projects chaired by Vladimir Putin, Moscow, 25 November 2016, http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/53333.

[9] Sergei Blagov, “Russia’s Far East Moves Toward Hosting APEC Summit”, Jamestown Foundation Eurasia Daily Monitor 9, Issue 155, 14 August 2012, https://jamestown.org/program/russias-far-east-moves-toward-hosting-apec-summit/; Dragoș Tîrnoveanu, “Russia, China and the Far East Question”, The Diplomat, 20 January 2016, http://thediplomat.com/2016/01/russia-china-and-the-far-east-question/.

[10] Ol’ga Kuvshinova and Aleksandra Prokopenko, “Minekonomrazvitiia prognoziruet eshche 20 let stagnatsii [Ministry of Economic Development Predicts another 20 Years of Stagnation]”, Vedomosti, 20 October 2016, vedomosti.ru/economics/articles/2016/10/20/661689-20-let-stagnatsii.

[11] Masaaki Kuboniwa, “Diagnosing the ‘Russian Disease’: Growth and Structure of the Russian Economy”, Comparative Economic Studies 54, Issue 1 (2012), 121–148; Shinichiro Tabata, “Observations on Russian Exposure to the Dutch Disease”, Eurasian Geography and Economics 53, Issue 2 (2012), 231–243.

[12] Expanded Board Meeting of the Ministry of Finance, Dmitry Medvedev Opening Remarks, Moscow, 20 April 2016, http://government.ru/en/news/22732/. It was President Barack Obama who in January 2015 referred to Russia’s economy as being “in tatters”: Remarks by President Obama in State of the Union Address, Washington DC, 20 January 2015, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2015/01/20/remarks-president-state-union-address-january-20-2015.

[13] The Reserve Fund exists to support the budget in difficult economic times. The National Development Fund is supposed to cover future deficits in the Pension Fund, but has been increasingly used to cover budgetary spending.

[14] Kirill Rogov, “Откуда роста не ждать [Why Not Wait for Growth]”, Vedomosti, 2 November 2016, vedomosti.ru/opinion/articles/2016/11/02/663293-otkuda-ne-zhdat.

[15] This is my translation of the awkward Russian word tselevoi.

[16] Raiding is the illegitimate use of administrative and legal procedures to seize businesses, most notoriously in recent times by government officials, very often in collusion with business rivals of the target firm.

[17] Items generally defined as ‘military expenditure’ but which are not funded from the Russian defence budget include military pensions and spending on military education, health, etc, as well as paramilitary troops. Julian Cooper, “The Russian Budgetary Process and Defence: Finding the ‘Golden Mean’”, Post-Communist Economies, forthcoming, 2017.

[18] Gudrun Persson (ed), Russian Military Capability in a Ten-Year Perspective — 2016, FOI-R-4326-SE (Stockholm, FOI Swedish Defence Research Agency, 2016), 138.

[19] Dmitrii Rogozin, “V bitve tekhnologii pobezhdaet dal’novidnyi’ [In the Technological Struggle the Far-Sighted Win]”, Rossiiskaia Gazeta, 30 October 2016, https://rg.ru/2016/10/30/dmitrij-rogozin-v-bitve-tehnologij-pobezhdaet-dalnovidnyj.html.

[20] World Bank, Pathways to Inclusive Growth: Russian Federation — Systematic Country Diagnostic (Washington DC: World Bank Group, 2016), 8–9.

[21] A series of decrees issued by Putin after he returned to the presidency in May 2012, which gave legal force to the promises he made in the presidential election ‘campaign’.

[22] The provision of credits to defence industry enterprises, which was used from 2012 to 2014 to get the rearmament program off the ground, has been abandoned and a large chunk of the debt written off. It is not yet known whether the new system of staged advances will keep costs and enterprises’ financial health under control.

[23] Any costs of such credits should be added to other costs of great power commercial behaviour, such as the provision of subsidised gas to favoured clients and the propping up of the economies of various dependencies in its claimed sphere of influence.

[24] In current circumstances, the focus with regard to oil and Russia’s dependence on it is on demand and price. There is, however, a long-running debate over Russia’s capacity to maintain supply into the future. Here it is assumed — possibly unsafely — that Russia is able to maintain output with costs and taxes at levels such as to allow returns to both producers and the state at sustainable levels.

About the Author

Stephen Fortescue is Honorary Associate Professor in Russian Politics at the University of New South Wales and Visiting Fellow at the Centre for European Studies, Australian National University. His areas of research interest include the contemporary Russian policymaking process, business–state relations, and Russia’s commercial involvement in the Asia Pacific. He received his PhD in Soviet Politics from the Australian National University.