New Caledonia’s independence referendum: Local and regional implications

As 30 years of peace agreements come to an end, stability in New Caledonia is now at risk

- New Caledonia faces an uncertain future as it prepares for its last local elections under the Noumea Accord, and as it enters a four-year process ending 30 years of peace agreements.

- The continued stark ethnic divide over independence revealed in the November 2018 referendum, the first of potentially three such votes, revives old tensions and complicates essential discussions about future governance, which will have consequences for France, Melanesian neighbours and the wider region.

- While strategically Australia benefits from continued French regional engagement, its support should not be at any cost.

Executive Summary

After a long history of difference, including civil war, over independence, New Caledonia’s 4 November 2018 referendum began a self-determination process, but ended 30 years of stability under peace accords. Persistent ethnic division over independence revealed by this first vote may well be deepened by May 2019 local elections. Two further referendums are possible, with discussion about future governance, by 2022, amid ongoing social unease. Bitter areas of difference, which had been set aside for decades, will remain front and centre while the referendum process continues.

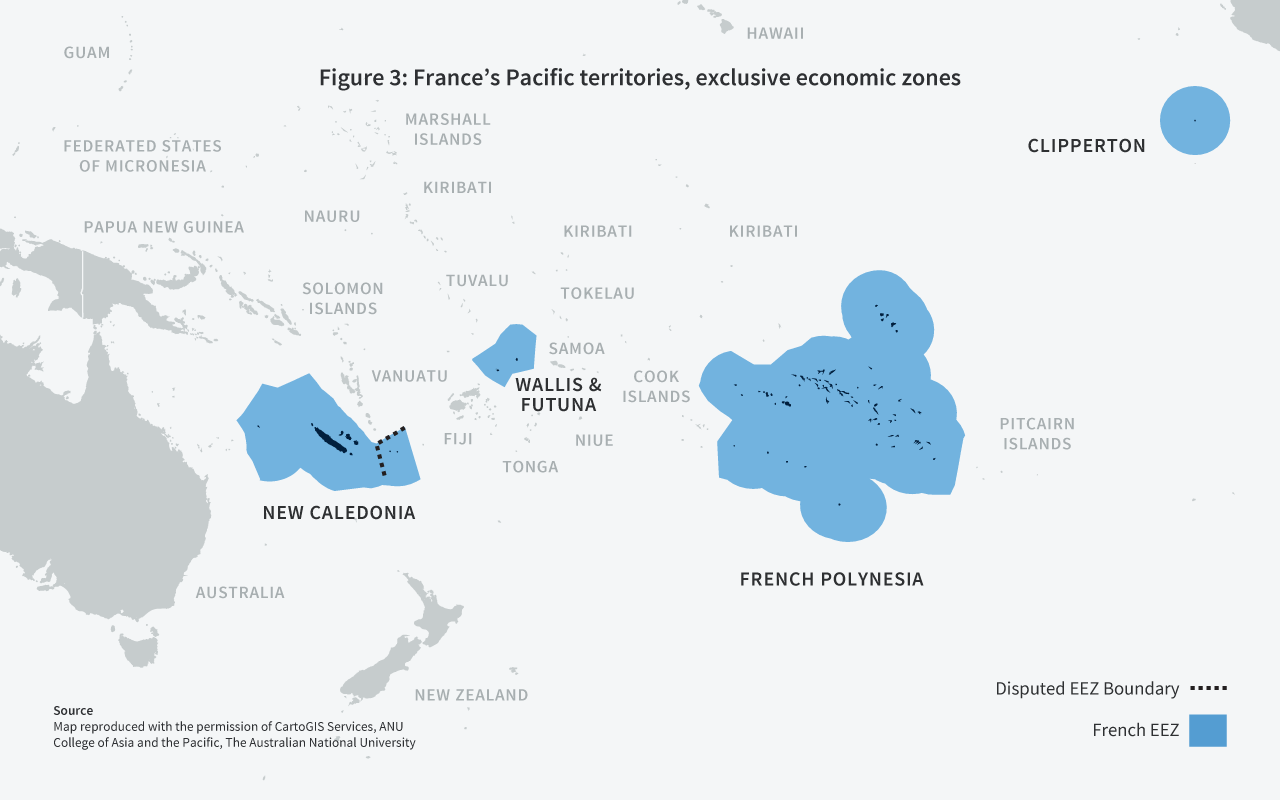

Key strategic interests are at stake for France, whose Pacific territories add ballast to its global leadership status. The challenge for France is to retain a necessary impartiality over the four-year process, when it wants to hold on to New Caledonia and its other global possessions. The process is being watched by neighbouring Melanesian countries, Pacific Islands Forum governments and the United Nations, all of which have long shaped and monitored New Caledonia’s decolonisation. They maintain an interest, and influence. Australia should encourage France’s constructive, harmonious regional engagement irrespective of New Caledonia’s decision about its future.

Introduction

On 4 November 2018, New Caledonia held a long-promised referendum on independence, with just under 57 per cent of voters choosing to stay with France.[1] The vote represents a turning point for France’s principal Pacific territory and Australia’s close neighbour as it begins the final phase of the Noumea Accord and associated agreements that ended civil war and have underpinned peace and stability for the past 30 years.

Provincial elections on 12 May 2019 will be the last under the peace agreements, and will decide the political balance for this self-determination phase. After a relatively strong vote to leave France in November, independence groups may well increase their support. This would further feed the continuing sharp ethnic divide highlighted in the referendum, and complicate French efforts at neutrality. Up to two more referendums are likely by 2022 and the results will be equally divisive. Dialogue is now the only way to surmount ethnic difference and to determine future governance. However, dialogue must also address remaining areas of deepest contention, not least whether or how to remain with France under UN options of independence, integration or partnership.

The strategic stakes are high for France, as it seeks to oversee fair votes, aware that outcomes in New Caledonia will have knock-on effects on French Polynesia and its other territories. France has sharpened its rhetoric accordingly, particularly on its self-ascribed role as a counterbalance to China.

France’s Pacific territories underpin its global leadership claims in the United Nations, in Europe and as a United States ally, bestowing privileged sovereign access to regional consultation tables as the Pacific overtakes the Atlantic in geostrategic importance. Its Pacific territories’ extensive exclusive economic zones alone make France the world’s second maritime nation after the United States. New Caledonia is the jewel of France’s overseas possessions, its regional military headquarters, base for scientific research, and site of strategic mineral reserves including nickel, chrome, cobalt and hydrocarbons, the latter shared with Australia with whom France has enhanced its defence links.

France’s Pacific policies have been disruptive to the region in the recent past, and can be again. Island leaders, who influenced French decolonisation policy, retain a watchful interest.

As Australia implements a refreshed Pacific policy, it needs to be clear about its own interests. New Caledonia has been the one neighbouring Melanesian archipelago that has been relatively stable. New uncertainties there coincide with, and may influence, an independence referendum in Bougainville, West Papuan separatism in Indonesia, and the process of returning to normalcy in Solomon Islands after the withdrawal of the Australian-led peace restoration mission. They also emerge at a time of strategic adjustment in the wider region, as new relationships, including with China, subsume traditional partnerships.

This Analysis explores what is at stake in this final stage of peace agreements, both for New Caledonia and for France. It looks at the historical context of the forthcoming referendums, the first referendum outcome and next steps in New Caledonia’s self-determination process, including the upcoming provincial elections and how they might determine the political balance for negotiating future governance beyond the Noumea Accord. It also identifies the implications of New Caledonia’s independence referendum process for the territory, France, the wider region, and Australia.

The referendum process

This is the third time New Caledonians have voted on independence. The current referendum process is the result of a series of agreements ending civil war in the 1980s. France negotiated these agreements after two decades of lobbying by Pacific Island states, which opposed France’s decolonisation policies and its nuclear testing in the Pacific.

The first independence vote was in 1958, when 98 per cent of voters supported staying with France,[2] in the context of De Gaulle’s commitment to deliver further autonomies within the “national community”.[3] France used this vote as justification for not listing its territories as dependent entities with the United Nations. New Caledonia’s sole party at the time, the Union Calédonienne (UC), which included both indigenous Kanaks and European settlers, sought greater powers from France.

Throughout the 1960s, development of the territory’s prime resource, nickel, accelerated.[4] As local authorities sought to engage other foreign partners, France reasserted its primacy. While bringing in French experts, it pursued an overt policy of attracting immigrants from the metropolitan and French territories specifically to outnumber the indigenous people, the main proponents of independence. In 1972 the French Prime Minister wrote that, “In the long term, the native nationalist claim will only be avoided if the non-native communities represent a demographic majority”.[5] At the time, France’s highest priority was retaining French Polynesia, where France was conducting nuclear tests underpinning its nuclear deterrent strategy. With the potential for flow-on effects to French Polynesia, France did not want to lose its grip on New Caledonia.

France introduced ten statutes from 1957 to 1988, most rolling back local autonomies.[6] By the late 1970s, the UC party had split into two. One was a mainly Kanak coalition, now known as the Kanak and Socialist National Liberation Front (FLNKS), seeking independence. Related FLNKS concerns were immigration and the redistribution of nickel revenues. The other was the loyalist party, Rally for New Caledonia in the Republic (RCPR), committed to remaining with France.

The leaders of the newly independent regional island states supported FLNKS. They formed the South Pacific Forum in 1971 — renamed the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF) in 2000 and now the region’s pre-eminent political gathering[7] — after France had opposed their participation, and vetoed political discussion, in what is now the Secretariat for the Pacific Community (SPC), based in Noumea.

Regional opposition to French policies increased. In the mid-1980s, the Melanesian Spearhead Group (MSG) was formed to support FLNKS independence demands.[8] In 1986, Pacific Island states successfully secured unanimous support in the UN General Assembly (UNGA), over France’s opposition and abstention, to relisting New Caledonia as a non-self-governing territory subject to UN Decolonisation Committee oversight.[9]

At the same time, FLNKS calls for independence mounted. By 1984, New Caledonia was in a state of incipient civil war. France organised a second independence referendum in 1987, to approve one of its statutes. FLNKS boycotted the referendum, as citizens resident for only three years were entitled to vote, diluting the Kanak vote. In 1988, FLNKS frustration culminated in an attack on French police, taking police hostages at Gossanah Cave on Ouvéa island. The French Government reacted forcefully — 19 Kanaks and six police were killed. It was the Gossanah confrontation, along with the successful regional anti-France UN campaign, that led France to a re-examination of its approach to New Caledonia.

The Accords

After France’s negotiations with FLNKS leader Jean-Marie Tjibaou and RPCR leader Jacques Lafleur, the Matignon–Oudinot Accords were signed on 26 June 1988. Securing compromise was difficult. The Accords promised an independence vote in 1998, and provided for a redistribution of nickel production and revenues. They also created three provinces: Southern Province, around mainly European Noumea, and Northern and Loyalty Islands Provinces in the Kanak heartlands. Essential to the negotiations was agreement on a restricted electorate for provincial elections, with voting for those elections confined to those resident in 1988 and their descendants.

Support for the Accords was fragile. Less than a year after the Accord was signed, Tjibaou was assassinated by a radical independence supporter.

Despite this fragility, the Accords presided over ten years of growth and development. Tensions remained, however. In 1991, Lafleur proposed a “consensual solution” to head off an independence referendum, citing the risk of returning to war. Eventually all parties agreed to defer the potentially explosive referendum. The pro-independence group hoped that with more time they could develop the experience needed to manage an independent “Kanaky”. The loyalists saw an extension as providing time for further economic development and redistribution to encourage independence supporters to see the benefits of remaining with France.[10]

The deadline for the referendum was finally extended to 2018 when the French State, loyalist and independence parties signed the Noumea Accord on 5 May 1998.[11] The Accord for the first time acknowledged the Kanak identity as having been under attack by colonisation. It affirmed a “common destiny”, meaning that Kanak, long-standing European and other residents all shared a rightful place in New Caledonia.

Once again, restricting the electorate for provincial elections to citizens resident for ten years to 1998 was fundamental to the agreement.[12] The Accord provided for a Congress drawn from the three provincial assemblies, elected every five years, and a collegial government (cabinet). It set out a scheduled handover of specified powers, with France retaining the “core” sovereign powers (defence, foreign affairs, currency, law and order, and justice). New Caledonia was given sui generis status, with unique powers to legislate on its own.[13]

Underpinning the Noumea Accord was an “economic rebalancing” aimed at addressing inequities. The 1998 Bercy Agreement enabled Northern Province to construct and own a majority 51 per cent share in a new multi-billion dollar nickel processing plant at Koniambo. A massive new plant would also be constructed at Goro in Southern Province.

At the behest of the independence group, France acknowledged New Caledonia as a “non-self-governing territory” in the United Nations.[14] France accordingly reported annually to the UN Decolonisation Committee thereby committing to decolonisation within three UN options — independence, independence-in-association, or integration with the major power.[15]

Implementation of the Accords

The 1988 and 1998 Accords have overseen 30 years of stability and economic growth in New Caledonia, watched closely by the Pacific Islands Forum and the United Nations.[16] The new political institutions have generally worked well, although they remain fragile, especially given that both loyalist and independence parties have become more fragmented. New Caledonia’s 54-member Congress comprises representatives drawn from each provincial assembly.[17] The Northern and Islands Provinces have remained predominantly Kanak, and the political base of the pro-independence groups. The Southern Province remains centred on Noumea and its surrounds, and is predominantly European, although with increasing Kanak inflows due to urban drift.

Over the four elections peacefully held since 1999, the pro-France groups have retained the majority in Congress. However their majority has weakened. Independence groups increased their representation from 18 to 25 seats from 2004 to 2014, while loyalist numbers diminished from 36 to 29 seats.

Both sides have fragmented, the loyalists seriously so. The Calédonie Ensemble (CE Caledonia Together) is now the single largest loyalist party in the Congress, where it holds 15 of their 29 seats, their remaining 14 seats spread across a range of smaller parties and coalitions including what is left of Lafleur’s rump RPCR. A new hard-line loyalist Les Republicains Calédoniens (Caledonian Republicans) was formed just a year before the November referendum.

The pro-independence side remains dominated by the loose FLNKS coalition, comprising the UC, itself divided, and the UNI-Palika (National Union for Independence — Party of Kanak Liberation), which occasionally dissociates itself. Of the 25 Congress seats held by the independence parties, the UC holds nine, Palika seven, the core FLNKS six, and three small parties one seat each.

These divisions have put pressure on the government (cabinet), which consists of six loyalist and five independence members reflecting respective party representation in the Congress. While the Noumea Accord prescribes a collegial approach, since the work of government requires legislative votes, the pro-France majority has prevailed. However, issues such as which flags to fly, nickel exports to China, and even the election of a president, have rendered the government moribund for months. Indeed, divisions over electing a president ground the government to a halt at the end of 2017, less than a year before the referendum. This intra-loyalist deadlock was broken by the major loyalist party securing support from the pro-independence side. Such collaboration has been evident in the Congress too, and provides a base for the necessary cross-group exchanges in the discussion process for the final phase of the Noumea Accord.

A critical element of the political machinery has been the annual meetings in Paris of the Committee of Signatories to the Accord, chaired by the French Prime Minister. Working groups focus on a range of functional aspects of the Accord’s handovers of responsibilities. The Committee has generally played a positive role but has been weakened by dissident members withdrawing from time to time. It also includes new leaders as new parties have formed, with the more divided loyalists over-represented, thus not reflecting electoral realities.

Despite the limitations, the government, Congress, and Committee of Signatories have been able to achieve handovers of many responsibilities and shared powers to the local government. New Caledonia was quick to use its new regional treaty-negotiation powers to conclude an Economic Arrangement with Australia and a cooperation agreement with Vanuatu in 2002. However, it was slow to take up other designated foreign affairs powers. Still, by the end of 2018, it was a full member of the Pacific Islands Forum, the Secretariat for the Pacific Community, and other technical organisations.[18] It has one diplomatic delegate, in Wellington albeit within the French Embassy, with four others in training for similar attachment in Canberra, Port Moresby, Vila, and Suva. New Caledonia’s External Affairs Unit is still run by a former French official.

The Noumea Accord promise of more equitable sharing of nickel production and revenue has generally been kept. In 2017 Dominique Katrawa was the first Kanak appointed as CEO of the colonial nickel company, SLN (Société le Nickel).[19] New Caledonia has been granted around 34 per cent of SLN shares, although independence groups have sought 51 per cent.[20]

Production has begun in both multi-billion dollar nickel plants, at Koniambo in the North and Goro in the South. Northern Province has successfully managed its 51 per cent share of the Koniambo project. It negotiated joint processing ventures with Korea (Posco) and with China (Yichuan), its principal market, and owns 51 per cent of Yichuan’s processing plant at Yangzhou.[21] Indeed, the most adventurous local efforts at international engagement have been by the Kanak Northern Province in pursuit of nickel markets in North Asia.

Despite the Accord’s successes, there have been weaknesses. Loyalists challenged early the basis of the restricted electorate, which was fundamental to reassuring Kanak independence groups fearful of being outnumbered after years of concerted immigration. Loyalists took their challenge to French and international courts. They claimed the ten-year voter qualification to 1998 should apply to each five-year election (“sliding” to 1999, 2004, 2009, and 2014). Only in 2007, after these courts confirmed the validity of the independence claim to a “frozen” ten-year residency to 1998, did France confirm that interpretation via legislative amendment.[22] The loyalists’ stance undermined pro-independence confidence in the good faith of the loyalists and indeed of France, and highlights the importance of international structures in ensuring fair implementation of New Caledonia’s political compromises.

Another key failure has been the inability to achieve full integration of many Kanak youth into the economic life of the territory.[23] Kanak young people living in villages find it difficult to succeed in the rigid French education system. Dropping out, turning to drugs, and drifting between villages and Noumea’s squat settlements is the fate of many, with some resorting to petty crime. The alienation of Kanak youth has led to sporadic violence including at St Louis near Noumea and elsewhere, and to a pattern of burglaries and personal attacks beyond the norm in metropolitan France, perpetrated by young Kanaks against Europeans.[24] In 2011, the visiting UN Special Rapporteur gave a devastating account of the social place of Kanaks:

“There are no Kanak lawyers, judges, university lecturers, police chiefs or doctors, and there are only six Kanak midwives registered with the State health system, out of a total of 300 midwives in New Caledonia … [Kanaks] are experiencing poor levels of educational attainment, employment, health, over-representation in government-subsidised housing, urban poverty ... and at least 90 per cent of the detainees in New Caledonian prison are Kanak, half of them below the age of 25.”[25]

Very little has changed since. In Northern and Islands Provinces, some Kanaks are involved in political leadership and administration, but most administrators are French.

The 2018 referendum

Given political division and fragmentation, and underlying social unease, it is not surprising that differences were acute in the lead-up to the first referendum under the Noumea Accord, with the vote posing serious risk factors for the future.

The parties could barely agree even that the vote take place. The Noumea Accord (Article 5) provides that the local Congress could decide, with three-fifths support, to hold a referendum any time after its election in 2014, on the basis of a uniquely defined electorate confined to citizens with 20 years residency to 2014, with France to convene the referendum if the Congress could not agree to do so.

As late as 2017, one loyalist leader was calling for a new agreement to defer the referendum again, by up to 50 years.[26] A referendum date was only agreed by Congress at the latest possible time, April 2018, for the latest date possible under the Accord, 4 November 2018. It was only with the personal involvement of French Prime Minister Édouard Philippe at a 15-hour meeting in Paris, that local leaders could agree even to the wording of the question to be put: “Do you want New Caledonia to accede to full sovereignty and become independent?”[27]

The Accord provides that, if the result is “no” to independence on the first vote, a further vote can be held within two years if one-third of Congress calls for it; if the result remains “no”, a third vote can be held on the same basis. The independence parties have always held at least one-third of Congress seats, so a further vote or votes are likely, in 2020 and 2022. After a third “no” vote, the parties must conduct discussions. Thus, the final phase of the peace accords could extend over four years. The bitter divisions set aside until 2018 will now be front and centre possibly until 2022.

Those differences have been sharpened as a consequence of the late timing of the first referendum. If Congress had initiated the process immediately after its election in May 2014, as provided for in the Accord, the potentially four-year process would have been completed by November 2018, within its five-year term. However, the first vote will now be followed by provincial elections to renew Congress’ mandate, due 12 May 2019. Only after Congress has reconvened can it call for a second referendum. These are critical elections, as they will determine the political balance for negotiating future governance beyond the Noumea Accord. Both sides are doing all they can to increase their support.

The polarising effect of the impending provincial elections was evident well before the referendum, with the restricted electorate again at issue. A few days before the vote, hard-line loyalist parties called for the cancellation of the second and third referendums. After the vote, they demanded the special restricted electorates for the provincial elections and the final votes be revoked, propositions that are anathema to the independence groups. On the independence side, a small radical union-based party called for a boycott of the first referendum on the basis of inaccurate voter lists.

Not surprisingly, the list of eligible voters for the referendum, unique in its requirement of 20 years’ residence to 2014, remains a focus of bitter dispute. The role of the United Nations in calming differences has been critical. Both sides have disputed the lists for years, the independence groups taking their concerns to the United Nations in 2015.[28] Their allegations that France’s oversight commissions were weighted to the pro-France side proved justified. This led France to invite the United Nations to oversee aspects of the list preparation process in 2016 and 2017. By the end of 2017, independence groups had negotiated automatic general registration for indigenous Kanaks in return for a softening of the definition of “material interests” for eligible non-Kanaks[29] — that is, the required proof of continued connection to New Caledonia if they have been absent. To maintain legitimacy and bolster confidence, France ensured voters could check and appeal their eligibility until the day of the vote.

The referendum outcome

The outcome of the vote saw 56.7 per cent in favour of staying with France, with 43.3 per cent supporting independence.[30] The decision to stay with France was predictable. However, there were some surprises. The first was the convincing turnout of 81 per cent. This is a recent historical high, compared with 27 per cent for the last European elections, around 40 per cent for French parliamentary elections, and 70 per cent for local provincial elections.[31] While reflecting the narrower electorate, the high turnout showed that voters prioritised the self-determination vote over other elections.

The high turnout lent strong legitimacy to the referendum both in New Caledonia and beyond. No objections have been raised by any local party, the 120 registered foreign journalists present, or the official missions from the United Nations and the Pacific Islands Forum who observed the vote, although the latter are yet to submit their reports.[32]

The second surprise for some was the relatively large 43 per cent of voters who supported independence. Predictions by senior French officials and some limited polls suggested a “no” vote of more than 60 per cent,[33] with loyalist leaders predicting at least 70 per cent.[34] Yet the result should not have surprised. It reflected the balance in Congress, where loyalists currently hold 53.7 per cent of the seats, and independence groups 46.3 per cent.

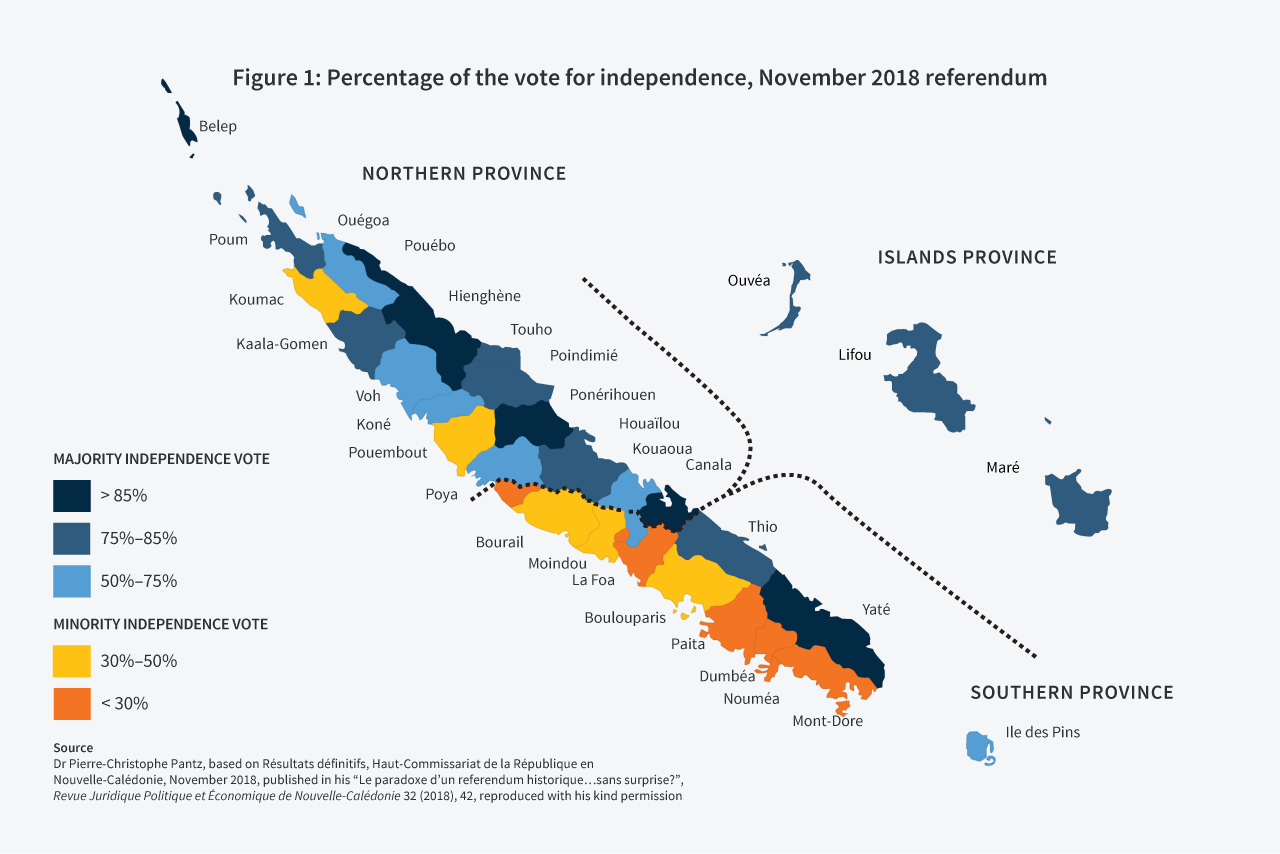

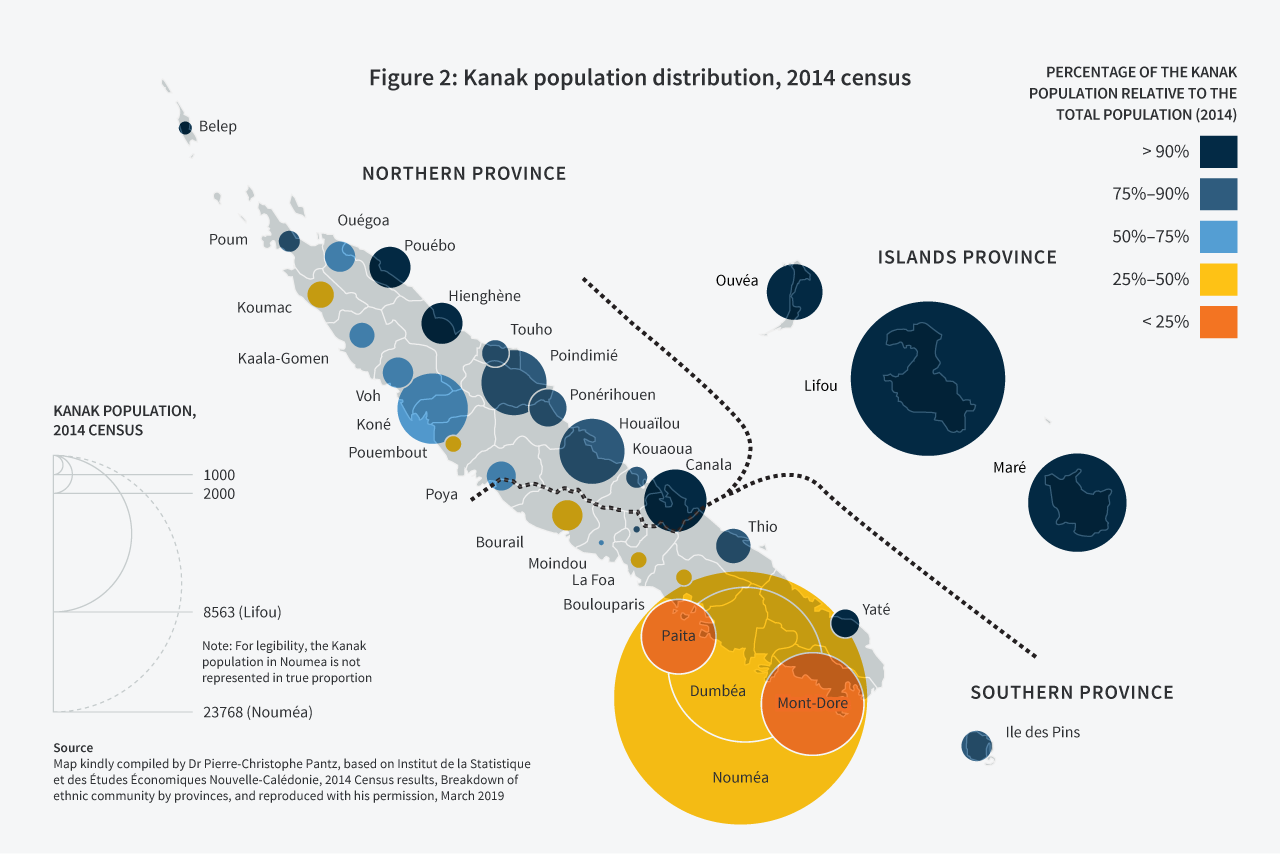

The most significant feature of the outcome was the continued unmistakeable ethnic divide, with the “yes” vote clearly from Kanak areas in the north and east of the main island and the Islands Province.[35] The trend was stark (see Figures 1 and 2 below). The “yes” vote reached as high as 80–90 per cent in the numerous communes in the Northern and Islands Provinces, with the “no” vote conversely 80–90 per cent in wealthy European communes in Southern Province.[36] Even in the mainly European greater Noumea area, around 26 per cent voted “yes”, mostly from communes with a recent Kanak population.[37]

A further feature of the referendum was the large number of young Kanak voters, evident in televised queues at polling stations, who clearly voted “yes”. Over the previous two years, independence groups had specifically targeted this group in rural visits.[38] Their effort to secure a large youth turnout was spectacularly successful.

The continued strong polarisation of the vote along ethnic lines presents challenges for the future.[39] The real shock for France and loyalists was that, after decades of devoting massive financial, diplomatic and political capital into demonstrating the benefits of staying French, so few Kanak independence supporters were convinced. France itself when presenting its voter lists had claimed that those of “customary status” (Kanaks) represented 46 per cent of the voter list,[40] to counter an FLNKS claim of 63 per cent.[41] Thus by France’s own measure, with 43.3 per cent voting for independence undeniably from Kanak areas, at best only 3 per cent of Kanaks supported staying with France.

Paradoxically, despite the majority “stay” vote, the result gives confidence to Kanak independence leaders. They calculate that, with natural population growth, numbers of 18-year-old Kanaks will add to their support in the second and third vote by 2022, whereas the number of largely European “no” supporters is likely to remain static. Despite the large 18 000 vote difference between the 2018 “no” and “yes” votes, the result vindicates the independence leaders’ strategy of negotiating the three-vote process; working with young Kanaks, convincing them to come out to vote for independence; and securing automatic registration for indigenous voters. It also hardens their commitment to the two subsequent votes.

A further feature of the pro-independence strategy is the targeting of the non-Kanak islander vote. Whereas Kanaks, all of whom can vote, constitute around 39 per cent of the population and Europeans 27 per cent, only some of whom are eligible voters, there are at least a further 11 per cent Pacific islanders (Wallisians 8 per cent, Tahitians 2 per cent and ni-Vanuatu 1 per cent), some of whom would be eligible.[42] To pursue these potential votes, independence parties sent missions to Vanuatu and French Polynesia to invoke clan connections. The Melanesian Spearhead Group also supported independence groups.[43] French Polynesian independence leader Oscar Temaru visited New Caledonia in the final weeks of the campaign to support the “yes” vote. The size of this potential vote is not insignificant. Non-Kanak islanders, who depend on New Caledonian employment, have mainly supported loyalists in provincial elections. However, in Paita and Bourail in Southern Province (home to many Wallisians), 26 per cent and 31 per cent voted “yes”, respectively, and the Bourail mayor believed many non-Kanak islanders voted “yes”. It is also likely they contributed to Noumea’s “yes” votes.[44]

No doubt all parties will concertedly target young Kanaks, Wallisians and other islanders in the future. Indeed, just months after the referendum, in March 2019, France signed an agreement giving ongoing guarantees by New Caledonia to Wallis and Futuna.[45]

Given manipulation of these groups in the past, and historical patterns of violence, such electioneering risks undermining peace.[46] More insidiously, the indisputable ethnic character of the first vote undermines the development of a “Caledonian identity” working for a “common destiny”.[47] It potentially complicates collaboration in the years ahead.

A further worrying feature of the first referendum is the unrest surrounding the vote. As soon as polling booths closed, violent protests broke out and continued for weeks, including the burning of cars, buildings and schools, a return of the blockade at St Louis, and a new blockade at Paita on the main northern highway, Molotov cocktails, and even shooting at police. All these incidents involved young Kanaks. Before the vote, there had been over a dozen arson attacks over two years at an SLN mine in the Kanak east coast heartland. In August 2018 young Kanaks blockaded the site, objecting to development that had been approved by their elders. While the authorities ended the blockade a week before the vote, the youths reimposed it by voting weekend, and trouble at the site continued until French authorities stepped in again in late November 2018. Petty damage to schools and cars, and robberies continued in Noumea and other areas into 2019.

Given this uneasy situation, with loyalists calling for cancellation of the subsequent referendums, French leaders speedily reaffirmed the overarching role of the Noumea Accord. At the Committee of Signatories meeting on 14 December 2018 they presented French Council of State advice endorsing the provision for up to two further votes, and the continued application of the restricted electorate,[48] over continuing loyalist objections. One of the major independence parties, UC, boycotted discussion on social and economic inequalities, claiming these were New Caledonian responsibilities. These differences provide a sobering indication of the difficulties in discussions ahead.

Next steps in the referendum process

The events surrounding the referendum suggest a difficult time ahead in the final phase of the self-determination process, with deep divisions over independence and the restricted electorate spiking at voting times, and further unrest as both sides pursue the votes of sensitive groups. Divisions are sharpened by the confidence, and perhaps unrealistic expectations, of the independence side buoyed by the first vote results, while loyalists claim to have won the contest. Long-standing close observers have noted an increase in loyalist racist discourse and fear reminiscent of the 1980s.

There are several milestone events ahead: the 12 May provincial elections, and two possible further referendums in 2020 and 2022. If one of the referendums favours independence, New Caledonia will become independent after a period of agreed transition.[49] If the answer remains “no”, discussions about the future assume prime importance, to determine the terms of either independence-in-partnership or full integration. Given the divisions and unrest, discussion is now critical regardless of voting outcomes.

At this stage it is unlikely that independence groups can win a future referendum. They need to retain the turnout and votes they won in November 2018 plus attract at least 18 000 more.[50] Both they and the loyalists will court Kanak and non-Kanak votes among those who abstained in the last referendum.[51]

The pro-independence objective of winning a majority in the May 2019 provincial elections is more achievable, particularly if loyalists remain divided (and the final party lists show that six loyalist parties are competing in Southern Province alone). Independence groups only need to win three more seats to gain the majority in the 54-member Congress, where they currently hold 25. The narrower electorate than for the referendums (ten years residency to 1998) advantages the indigenous Kanak vote. If loyalists maintain their majority, divisions within their side suggest that the dominant loyalist party will need the support of independence parties to govern, as has been the case in recent years. Such collaboration, while fraught, exemplifies the spirit of the Noumea Accord.

The French Government has long understood that a viable future for New Caledonia demands consideration of indigenous independence views, regardless of voting outcomes.[52] Unlike some European residents, indigenous Kanaks are there to stay. French leaders have emphasised the need for dialogue. On the evening of 4 November 2018, President Macron publicly welcomed the referendum result and expressed pride in the vote to remain French. However, in leaked private comments he acknowledged that some would see the result as a “yes, maybe” to independence, or a “yes, soon”. He reportedly affirmed that it was “highly desirable” for New Caledonia to remain with France, and to achieve that “we must partially, progressively and genuinely decolonise”.[53] In January 2019, Overseas France Minister Annick Girardin described a future New Caledonia “associated” with France. She immediately “clarified”, after loud protest by loyalists, that the future would be defined “with New Caledonians who had expressed themselves clearly on 4 November”.[54] These high-level comments suggest that France is prepared to be flexible, and signal to loyalists that they must be too.

Under the Noumea Accord’s irreversibility provisions (Article 5), New Caledonia retains all the institutions and responsibilities, including shared responsibilities, devolved by France. Even so, and even if parties agree to continued full integration with France, future discussions will inevitably alter the status quo, because some aspects of current governance, such as restricted electorates, apply for the duration of the Noumea Accord only. Fundamental issues not mentioned in the Accord, such as immigration control and nickel development, must be addressed. And independence and loyalist leaders alike will want to secure further powers from France, regardless of voting outcomes.

France has laid the groundwork for discussion. It commissioned a study in 2013 outlining legal consequences of four different UN-consistent options: staying with France, independence, and two types of partnership.[55] After two years of consultation with political leaders, a 2016 report identified areas of difference and agreement over specific aspects of governance.[56] These will be indispensable starting points for the final talks.

There are signs that key leaders on both sides are prepared to compromise. In November 2017, the pro-independence Palika party’s Paul Néaoutyine said it would consider “full sovereignty in partnership with France”.[57] Two weeks later, leader of loyalist party Calédonie Ensemble, Philippe Gomès, set out detailed areas under the five core sovereign responsibilities that could be “Caledonised”.[58] At the December 2018 Committee of Signatories meeting, Gomès said his party favoured negotiations with independence groups, to substitute a new political framework for the five-year provincial mandates.[59]

The likely focal points of discussion and areas for any change less than full independence include:

- the three areas specified in the Noumea Accord that must be addressed in the final phase:

- the core sovereign powers: foreign affairs, defence, currency, law and order, and justice

- international status, including the question of a UN seat

- citizenship issues, meaning any special voting and employment rights for long-standing residents

- powers over the media, tertiary education, municipal administration[60]

- immigration control

- management of the nickel industry

- handing over control of the land distribution agency

- addressing social and economic inequalities, particularly for Kanak youth.

All of these issues are sensitive. The challenge will be to maintain productive discussion without bitter division surfacing to obstruct progress or disrupt the peace, especially around provincial and referendum votes. Some close French observers suggest serious discussion will not begin until after a second referendum (most likely 4 November 2020). With French presidential elections in April 2022, they hope parties might agree not to hold a third referendum, instead negotiating a future statute while the current president is in power.[61] Whether independence groups would forgo a third referendum is open to serious question.

France’s position

Against this troubled history, and under the regional and international gaze of the Pacific Islands Forum, Melanesian Spearhead Group and United Nations, President Macron in May 2018 formulated as France’s overarching objective the holding of a referendum that would be seen widely as “legitimate” and “incontestable”.[62] France unreservedly achieved that aim first time round. There has been no questioning of the result from domestic or international sources. A continuing challenge is to maintain this record over a further two possible referendums, given the tension between France’s role as organiser of the final process and its clear desire, expressed by President Macron on the evening of the first vote, to retain New Caledonia as part of France.[63]

Macron’s enunciation of France’s wish to keep New Caledonia reflects a series of French assessments over the past ten years highlighting the strategic value of their global possessions, and New Caledonia in particular.[64] France’s string of possessions[65] bolster its leadership claims as one of the five Permanent Members of the UN Security Council, in the European Union and NATO, and as a US ally. The French Pacific territories’ exclusive economic zones (EEZ) alone make France the global number two maritime nation (Figure 3), after the United States and before Australia, with an EEZ three times larger than China’s.[66]

As a sovereign resident power, France has a privileged position at regional tables such as Quadrilateral Defence Meetings with the United States, Australia and New Zealand, with the Pacific arguably overtaking the Atlantic in geostrategic importance, and other players seeking to engage in the region.[67] New Caledonia has replaced French Polynesia as France’s Pacific strategic priority. It is now the headquarters of its Pacific military and scientific research presence,[68] with reserves of sought-after minerals (nickel, chrome, cobalt) and prospective hydrocarbon resources off its shores shared with Australia, a strategic ally with whom France has strongly reinforced links.[69]

President Macron was frank about France’s strategic interests during his May 2018 visit to Noumea. He defined his vision of an Indo-Pacific axis stretching from Paris to New Delhi, Canberra and Noumea, of which New Caledonia could be part, if it remained French. He highlighted the value of French defence and security protection, particularly against China’s “hegemony”, an apparent warning given Northern Province’s nickel cooperation with Chinese companies. At the same time, he promised new investment to diversify New Caledonia’s economy if it stayed with France.[70]

In a clear economic nudge to remain with France, SLN, the oldest and most productive nickel plant employing 2000 people and owned by French government-backed Eramet, suggested after the first referendum that it may have to close given cost push factors including the effect of the long blockade at Kouaoua.[71]

New Caledonia’s self-determination process is the more important because of the potential demonstration effect on France’s other strategic assets around the globe. French Polynesia’s independence leader, Oscar Temaru, who campaigned with independence groups in New Caledonia, has already called for a self-determination referendum for the Maohi (long-standing Tahitian) people.[72] Separatist delegations from France’s Corsica and Basque regions were in New Caledonia campaigning for the independence camp. France does not want its network of overseas possessions to unravel.

France has worked to improve its pariah image of the 1980s in the region, with success. Having suspended nuclear tests and addressed decolonisation concerns in New Caledonia, it has cooperated in the 1992 FRANZ (France, Australia and New Zealand) arrangement to provide emergency assistance, fisheries surveillance, and intelligence to regional countries; participated in defence exercises with Melanesian partners, Australia, and New Zealand; and given modest aid and climate change assistance through regional technical bodies and EU support. Macron’s approach shows France wants to continue to handle New Caledonia’s future in a way consistent with regional expectations.

With its strategic declarations and regional efforts, there is more at stake for France in losing New Caledonia, or mishandling this final phase of the peace agreements, than ever before.

The inconsistencies in France’s claimed impartiality in overseeing the referendum process, and the potential for it again to create regional disharmony, are evident in its decision to send a naval vessel in January 2019, just after the first independence vote but with the referendum process yet to play out fully, to assert its claimed sovereignty over the islands of Matthew and Hunter. The islands are disputed between France/New Caledonia and Vanuatu. However, Kanak elders formally endorse Vanuatu clan claims to the islands, supported by pro-independence FLNKS. Both Vanuatu and FLNKS leaders immediately denounced France’s action.[73]

Regional implications

Some French officials have observed that regional fervour for New Caledonia’s independence cause has diminished if not disappeared.[74] They cite the Pacific Islands Forum admitting New Caledonia and French Polynesia as full members in 2016, before either had achieved independence, and the fact that the Melanesia Spearhead Group has recently pursued trade and economic activities, rather than political influence.

This is to ignore recent history. The Pacific Islands Forum and Melanesia Spearhead Group were created out of concern about French decolonisation policies. Those concerns have not disappeared. The Pacific Islands Forum has referred to New Caledonia’s decolonisation process in most of its annual communiqués since it was formed. Its members sponsored the UN General Assembly resolution relisting New Caledonia as a UN non-self-governing territory in 1986. It sent ministerial observer missions there in 1999, 2001, and 2004, and a high-level team to observe the November 2018 referendum. In 2013, three PIF members achieved the re-inscription of French Polynesia as a non-self-governing territory under UN decolonisation principles. France, taken by surprise, absented itself from the vote and bitterly denounced the move.[75] The decision by PIF to admit New Caledonia and French Polynesia as members in 2016 was controversial and divisive.[76]

Strong personal links remain between independence leaders in the French Pacific territories and regional leaders. New Caledonia’s independence delegations reached out to Vanuatu, French Polynesia, and the Melanesian Spearhead Group during the referendum campaign and received a supportive response. These islands will be concerned if the divisions, discussions, and campaigning in the next four years generate instability or disrespect for indigenous claims. Independence leaders will continue to draw on this support, just as France will continue to strengthen its own links and interests bilaterally, as well as in the Secretariat for the Pacific Community and the Pacific Islands Forum.

Neighbouring Melanesian fragilities

This final historic step in New Caledonia is taking place at a sensitive time for its Melanesian neighbourhood, where it has for the past 30 years been an example of stability. Any return to instability or unrest will add to existing fragilities there.[77]

The Melanesian Spearhead Group is closely interested in the territory’s self-determination outcome. It resists calls from New Caledonian loyalists to replace the FLNKS representative on the Group with a (loyalist) New Caledonian representative. The Group supports New Caledonia’s independence groups in the referendum process.

New Caledonia’s final self-determination steps coincide with a similar end process of the Bougainville Agreement in neighbouring Papua New Guinea. This Agreement was modelled on the Noumea Accord, ending secessionist disruption on Bougainville with a similar agreement to set aside an independence vote for a specified period. The Bougainville vote must be held by 2020 and is scheduled to take place in October 2019.[78] Secessionists there will have noted the relatively strong support for independence in New Caledonia’s first vote, and will take an interest in the May 2019 provincial election results.

Separatist supporters in West Papua are also closely watching. Membership of the Melanesian Spearhead Group, with its concern for Melanesian self-determination, is integral to West Papua’s own independence ambitions. In 2015, the Group granted Observer status to the United Liberation Movement for West Papua (ULMWP) while at the same time granting Indonesia Associate status. Indonesia has since resisted efforts by the ULMWP for full MSG membership, splitting MSG members Papua New Guinea and Fiji, who tend to support Indonesia, from Vanuatu and Solomon Islands. The Melanesian Spearhead Group has not yet responded to the ULMWP’s application for full membership.[79] While violence has erupted in West Papua periodically, it is perhaps no coincidence that shortly after New Caledonia’s referendum, on 1 December 2018, a symbolic “day of independence” from the Dutch, a violent protest resulted in the killing of 31 construction workers.[80] Claiming responsibility for the attack, a spokesman for the West Papua National Liberation Army referred to “the opportunity to determine our future through a referendum”.[81]

Solomon Islands is also at a delicate phase, adjusting to the withdrawal in 2017 of the Australia-led RAMSI mission with the risk of ethnic tensions re-emerging.[82] Fiji is consolidating its post-coup political processes, and Vanuatu is dealing with the aftermath of a devastating cyclone in 2015.

Broader shifts in the Pacific

Redefining governance in New Caledonia, and thereby the sovereign basis for the ongoing engagement of France, now a useful regional partner for Australia, coincides with strategic evolutions in the wider Pacific region. The most notable has been China’s increasing role in the Pacific, as it seeks to shore up sources of energy, fisheries and other resources, developing strategic infrastructure such as ports, airports, bridges and roads; and as it looks for international support in Pacific Island votes in international forums, imposing different political conditions to those of the West, often with disruptive effects.[83]

The presence of the new power has led to swift readjustment by traditional players. The US “Asia-Pacific pivot” in practice continued to leave Western alliance South Pacific leadership to Australia. Japan became more attentive, increasing its aid and regional engagement with the United States. Taiwan upped its aid and regular consultation mechanisms.[84] Australia and New Zealand strengthened their bilateral relationships with France, with defence activities in the South Pacific at their centre.[85] Australia announced a refreshed regional approach in November 2018, focused on defence and infrastructure development.[86]

The Pacific Island states are dealing with the consequences of this change. Their small bureaucracies are under pressure from the practical demands. For example, they now have regular summit meetings with Japan, China, Taiwan, India, and France.[87]

At the same time, the island states have reshaped their own patterns of intra-regional collaboration, within a concept of “friends to all”, including China.[88] While the principal forums, the Pacific Islands Forum and Secretariat for the Pacific Community, continue to engage traditional partners such as Australia and New Zealand, the island states have developed other patterns of cooperation. This is partly because the more significant newer players including the European Union (led by France) and China prefer bilateral rather than regional partnerships.[89] Pacific Island states are also working more with other small island states globally to address issues such as climate change and sustainable development.[90] They have developed new forums that do not include Australia and New Zealand, such as the Pacific Islands Development Forum from 2009 (born of Fiji’s exclusion from the Pacific Islands Forum after a military coup), and the Polynesian Leaders Group from 2011.[91]

However successful France has been in establishing itself as a constructive partner, island countries’ diplomatic resources are spread more thinly than ever, making it harder to exert influence. Moreover, tensions arise for the Pacific Islands Forum from their 2016 decision to accept New Caledonia and French Polynesia as full members, since, as French territories, they represent two French voices in the Forum sanctum.[92] PIF admitted these new French members in the expectation of aid and support from France, and so far France has not done much to respond. The Lowy Institute Pacific Aid Map barely registers French development aid, the amounts are so modest — at most A$100 million per annum, compared to Australia’s $1.3 billion.[93]

Uncertainty in New Caledonia will not help France to solidify regional support for the strategic place it wants in the Pacific. France must continue to ensure that the complex and difficult final stage of the Noumea Accord process plays out in a peaceful way respectful of all, but particularly of the indigenous Kanaks. Whatever the pressures from its loyalist constituency, France must retain its relatively neutral stance in organising the final stage consistently over the next four years. It should increase its aid to the region, and encourage genuine engagement by its territories in regional trade arrangements, to bolster regional understanding should things take a downward turn in New Caledonia.

Australia’s position and interests

Australia’s official position is to support the full implementation of the Noumea Accord including its self-determination provisions,[94] while not expressing a preference on the outcome. Australia will respect whatever choice New Caledonian voters make.

Still, Australia’s strategic interests are undoubtedly served by the constructive regional engagement of France. It is a well-resourced ally that in recent years has shown itself willing and able to share the strategic burden of promoting Western interests, as China and others become increasingly involved in the Pacific. Australia and France have strengthened their strategic partnership, with defence cooperation in the Pacific as the keystone,[95] including military exercises, cooperation in disaster response, a 2006 status of forces agreement, and a Mutual Logistical Support Agreement yet to be finalised, with Australian access to French bases in New Caledonia at its core. In 2016 Australia granted a $53 billion submarine construction contract to a French government company, capping a strong commercial defence relationship.[96] Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s revamped Pacific policy, announced on 8 November 2018 just days after New Caledonia’s independence referendum, named France as a partner in a vision of regional cooperation primarily focused on defence and security. It includes opening an Australian diplomatic mission in French Polynesia.

However, Australia’s regional priorities are not identical to France’s. France ultimately wants to retain New Caledonia for its strategic value and as an asset in its global leadership aspirations. Australia’s primary interest is in the stability and prosperity of its immediate region.

A key difference between Australia and France is France’s approach to China as it seeks to shore up support in New Caledonia. France sees China through the prism of France’s global leadership ambitions, of a type Australia does not claim for itself. While Australia remains alert to aggressive exertions of power regionally or inappropriate interference in its internal affairs, it acknowledges a key place for China in the region.[97] As Australia’s largest trading partner by far, arguably China matters more for Australia than it does for France.[98] There is no doubt that Australia’s strengthened Pacific policy is designed to build the region’s resilience and independence in the context of China’s increasing presence and influence. Still, when he presented his policy, Prime Minister Scott Morrison mentioned China only once, and then as a partner.[99]

In contrast, France projects a balancing role for itself in the Pacific against the rise of China. In Sydney in May 2018, President Macron, after describing France as a Pacific power because of its territories there, referred to the need for new dialogue with allies against China’s “totally reshaping” many regions.[100] A more recent French internal white paper describes “an increasingly assertive China … promoting its own world view”, and “hegemonic tendencies and unilateralist temptations”.[101] In the context of New Caledonia’s self-determination process, France’s approach is more pointed. In Noumea in May 2018, indirectly appealing to voters to remain with France, President Macron underlined France’s role as protector against a “China in the process of constructing its hegemony step by step … a hegemony which will reduce our freedom, our opportunities”.[102] Since then, loyalists have unashamedly played the “China threat” card with even stronger rhetoric, while advocating staying with France.[103] Such rhetoric is likely to sharpen as the referendum process plays out. Australia needs to be alert to these underlying motivations, and distinguish its China policy from the rhetoric of France.

Within New Caledonia, Australia should encourage France to maintain an impartial stance throughout the next steps in the self-determination phase, including the local elections, the two possible further referendums, and critical discussion about future governance, so that the outcomes are seen as legitimate in the region and beyond. Disruption in New Caledonia may contaminate neighbourhood countries, including most notably in Papua New Guinea, given the Bougainville challenge, where Australia has recently strengthened its military foothold at Lombrum.[104] It will also affect Indonesia and the West Papuan issue. Australia has a strong interest too in the harmony of PIF members who have been variously alienated and courted by France over decades, and who even today appear ambivalent over France’s conduct in its Pacific possessions.

Australia could draw down some credit from its strengthened relationship with France, and from its valuable support for French sovereignty in the region. Australia should call on France to set itself up for deeper regional engagement, beyond defence and existing links, regardless of the outcome of New Caledonia’s self-determination process. France can do this by increasing substantially the level of aid it currently provides. It could actively support open markets in the Pacific within existing regional frameworks, by leading an EU position in current renegotiation of Cotonou arrangements to more practicable EU access for small island states; and by supporting its territories in genuinely opening their markets. Australia needs to promote these changes, while being sensitive to the preoccupations within New Caledonia over the next four years as it redefines its future.

Conclusion

In New Caledonia, the stability provided by 30 years of agreements, now ending, is at risk. The 2018 referendum has revealed continued deep ethnic divisions over independence. The result heightens Kanak independence fervour and European loyalist fear, amid ongoing social unease. This makes it harder for France to be a neutral organiser of a tense self-determination process likely to extend over four years. Dialogue about future governance assumes prime importance, whatever the outcomes of possible future referendums.

The new uncertainties coincide with, and may exacerbate, evolutions in the immediate Melanesian neighbourhood, and the broader region as it adjusts to strategic change led by new partnerships, including with China. Regional countries and the United Nations have positively influenced New Caledonia’s self-determination process. Their ongoing engagement will be important to ensure a stable future for the French territory and the region. Australia’s policy advancing its own interests should be informed by these interconnections.

About the Author

Denise Fisher is a Visiting Fellow at the Australian National University’s Centre for European Studies, where she writes on France in the South Pacific. Denise was an Australian diplomat for 30 years, serving in Australian diplomatic missions as a political and economic policy analyst in Rangoon, Nairobi, New Delhi, Kuala Lumpur and Washington DC before being appointed Australian High Commissioner in Harare (1998-2001), accredited to Zimbabwe, Zambia, Mozambique, Angola and Malawi. She was the Australian Consul-General in Noumea, New Caledonia, from 2001 to 2004. Denise is the author of France in the South Pacific: Power and Politics. She holds a Master of Philosophy from the Australian National University and a Masters in International Public Policy from John Hopkins University.

Notes

[1] “Les résultats définitifs de la consultation du 4 novembre 2018”, Les services de l’État en Nouvelle-Calédonie, Gouvernement de la Nouvelle-Calédonie, http://www.nouvelle-caledonie.gouv.fr/Actualites/Referendum-Retrouvez-ici-les-resultats-definitifs-de-la-consultation-du-4-novembre-2018.

[2] The vote saw a 77 per cent turnout of the then 35 163 New Caledonian registered voters: “Proclamation des résultats des votes émis par le peuple français à l’occasion de sa consultation par voie de référendum le 28 septembre 1958”, Journal Officiel de la Republique Francaise, 5 October 1958, https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/jo_pdf.do?cidTexte=JPDF0510195800009177&categorieLien=id.

[3] Stephen Henningham, “Attitudes and Issues in New Caledonian Politics”, Pacific Affairs 61, No 4 (1988–89), 638.

[4] New Caledonia today holds at least 25 per cent of global nickel reserves.

[5] “À long terme, la revendication nationaliste autochtone ne sera évitée que si les communautés allogènes représentent une masse démographique majoritaire”, letter by French Prime Minister Pierre Messmer to his Overseas Territories Secretary, 17 July 1972, cited in Antoine Sanguinetti, “La Calédonie, summum jus summa in juria”, Politique aujourd’hui (1985), 26.

[6] The 1957 Defferre Law, 1963 Jacquinot Law, 1969 Billotte Law, 1976 Stirn Statute, 1979 Dijoud Law, 1984 Lemoine Law, 1985 Pisani Plan, 1985 Fabius Plan, 1986 Pons I Statute, 1988 Pons II Statute. For short summaries of each, see Appendix 2 in Denise Fisher, France in the South Pacific: Power and Politics (Canberra: ANU Press, 2013), 307–310, https://press.anu.edu.au/publications/france-south-pacific.

[7] See Fisher, France in the South Pacific, 51; Stephen Bates, The South Pacific Island Countries and France: A Study in Inter-State Relations (Canberra: Australian National University, 1990), 42; Greg Fry, “Regionalism and International Politics of the South Pacific”, Pacific Affairs 54, No 3 (1981), 455–584; and Stephen Henningham, France and the South Pacific: A Contemporary History (Sydney: Allen and Unwin, 1992), 197.

[8] MSG members included Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, the FLNKS (representing New Caledonia), and were joined in 1988 by Fiji.

[9] United Nations General Assembly Resolution 41/41A, Implementation of the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples, 2 December 1986, http://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/41/41.

[10] Leah Horowitz, “Toward a Viable Independence? The Koniambo Project and the Political Economy of Mining in New Caledonia”, The Contemporary Pacific 26, Issue 2 (2004), 291.

[11] The 1998 Noumea Accord: https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/affichTexte.do?cidTexte=JORFTEXT000000555817. An Organic Law of 21 March 1999 gave it effect: https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/affichTexte.do?cidTexte=JORFTEXT000000393606.

[12] The restricted electorate for the provincial elections differs to that for the final referendums, which is 20 years residence to 2014 (Noumea Accord, Article 5).

[13] New Caledonia became a “pays à souveraineté partagée” (country with shared sovereignty) empowered to pass “lois du pays” (laws of the land). Whereas some other territories can pass some administrative regulatory laws, and French Polynesia can pass “lois de pays”, such legislation is subject to Council of State approval. In New Caledonia’s case, laws are only revocable on appeal to the Constitutional Court. See Jean-Yves Faberon and Jacques Ziller, Droit des collectivités d’outre-mer (Paris: Libraire Générale de Droit 2007), 345, 368; and “Statut particulier: Nouvelle-Calédonie”, on French Government website “Collectivités-locales”, https://www.collectivites-locales.gouv.fr/statuts-nouvelle-caledonie-et-polynesie.

[14] Personal communication to author, independence leader, 18 November 2017.

[15] UN General Assembly Resolution 1541 (XV), Principles which should guide members in determining whether or not an obligation exists to transmit the information called for under Article 73e of the Charter, Annex, Principle IV, 15 December 1960, https://undocs.org/en/A/RES/1541(XV).

[16] See Denise Fisher, “France in the South Pacific: Countdown for New Caledonia – Review of the implementation of the Noumea Accord”, ANU Centre for European Studies Briefing Paper Series Vol 3, No 4 (May 2012), http://politicsir.cass.anu.edu.au/centres/ces/research/publications/france-south-pacific-countdown-new-caledonia-review-implementation-noumea.

[17] A total of 32 Congress seats from Southern Province’s 40 provincial seats, 15 from Northern Province’s 22, and 7 from Islands Province’s 14.

[18] New Caledonia is a member of the South Pacific Tourism Organization, Pacific Islands Development Program, South Pacific Regional Environment Program, Pacific Power Association, and the Oceanic Customs Organization. It has associated status in UNESCO and the Western Pacific WHO Committee.

[19] “Dominique KATRAWA appointed Chairman of SLN's Board of Directors”, News Release, 16 November 2017, http://www.eramet.com/en/news/dominique-katrawa-appointed-chairman-slns-board-directors.

[20] “Une entreprise calédonienne”, Société le Nickel Groupe Eramet, https://www.sln.nc/une-entreprise-caledonienne.

[21] See “Visite du Président Paul Néaoutyine en Chine”, Société minière du sud pacifique, 30 July 2018, https://smsp.nc/visite-du-president-paul-neaoutyine-en-chine/.

[22] The European Human Rights Court decision of 11 January 2005 noted the validity of the ten-year residence requirement taking into account the “local necessities” that justified it; the UN Human Rights Committee noted the provision was not contrary to the International Civil and Political Rights Convention: Fisher, France in the South Pacific, 103.

[23] Until the 1960s, few Kanaks had the opportunity to go beyond the level of primary education. Many remain in a subsistence economy. Family and kin obligations and customary exchange practices discourage entrepreneurship and the accumulation of capital. Kanak young people living in relatively crowded conditions in villages, and subject to many distractions in terms of family and customary ceremonies and events, find it difficult to succeed in the rigidly-academic French education system.

[24] “Délinquance: mise au point du Haut-Commissaire Thierry Lataste”, La Depêche de Nouvelle-Calédonie, Communiqué du 16 février 2017, 16 February 2018, https://ladepeche.nc/2018/02/16/delinquance-mise-point-haut-commissaire-t-lataste/.

[25] James Anaya, “The situation of Kanak people in New Caledonia”, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, James Anaya, UN Human Rights Council, UN Document A/HRC/18/35/Add.6, 23 November 2011, http://unsr.jamesanaya.org/docs/countries/2011-newcaledonia-a-hrc-18-35-add6_en.pdf.

[26] Pierre Frogier, “Intervention de Pierre Frogier — Rencontre avec le Président de la République”, Comité des signataires de l’accord de Noumea, 30 October 2017, http://www.rassemblement.nc/intervention-de-pierre-frogier-rencontre-president-de-republique/, accessed 5 December 2018; summarised comments made to the French Senate, “Accession à la pleine souveraineté de la Nouvelle-Calédonie”, Rapport au Sénat, 7 February 2018, http://www.senat.fr/rap/l17-287/l17-2872.html; and personal comments, senior L-LR leader, Noumea, November 2017.

[27] Compromises included the loyalists agreeing to drop reference to “remaining with France” and the independence side agreeing to include the word “independence”, which it had, paradoxically, sought to avoid in order to attract as many voters as possible: see Denise Fisher, “New Caledonia’s Referendum Question Agreed – but Future Questions Remain”, The Strategist, 5 April 2018, https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/new-caledonias-referendum-question-agreed-questions-remain/

[28] Roch Wamytan, “Déclaration au Comité 24 à l’Organisation des Nations Unies”, New York, United Nations, 29 June 2015, https://www.ncpresse.nc/Declaration-de-M-Roch-Wamytan-au-Comite-des-24-a-l-ONU_a4326.html.

[29] Section V, Relevé de conclusions, XVIe Comité des Signataires de l’Accord de Nouméa, Paris, 3 November 2017, https://www.gouvernement.fr/partage/9678-xvie-comite-des-signataires-de-l-accord-de-noumea-releve-de-conclusions.

[30] “Les résultats définitifs” 2018.

[31] European election rate reported in “Européens: les principaux résultats de la zone pacifique”, NC1ère, 26 May 2014, https://la1ere.francetvinfo.fr/nouvellecaledonie/2014/05/26/europeennes-resultats-en-nouvelle-calédonie-155617.html. In French parliamentary elections, first round, New Caledonian turnouts in 2017 were 40.85 per cent (Noumea) and 39.64 per cent (Dumbea): Electoral Results, Ministry of the Interior, https://www.interieur.gouv.fr/Elections/Les-resultats/Legislatives/elecresult__legislatives-2017/(path)/legislatives-2017//988/98802805.html. In provincial elections, turnouts were 74 per cent in 1999, 76.42 per cent in 2004, 72 per cent in 2009, and 69.95 per cent in 2014: Fisher, France in the South Pacific, 157, based on official results, www.nouvelle-calédonie.gouv.fr.

[32] The PIF mission issued an interim statement on 8 November 2018 concluding that despite some technical issues “there was a high degree of transparency and credibility of the process, and that the final result accurately reflects the will of the voters”: https://www.forumsec.org/interim-statement-from-the-pacific-islands-forum-ministerial-committee-to-the-new-caledonia-referendum/.

[33] Personal communications by senior officials, Paris, February 2017 and 2018, Noumea, November 2017; Anthony Berthelier summarised an I-scope poll in July–August 2018 predicting 63 per cent favouring staying with France, Quid Novi in September 2018 69–75 per cent, and Harris on 3 October 2018 66 per cent, although the samples were small, the respondents only self-identifying as eligible to vote, and margins were large: “Référendum en Nouvelle-Calédonie: ce que disent les derniers sondages”, Huffpost, 3 November 2018, https://www.huffingtonpost.fr/2018/11/03/referendum-en-nouvelle-caledonie-ce-que-disent-les-derniers-sondages_a_23579482.

[34] For example, “Philippe Gomès: ‘70% des Calédoniens voteront “non” à l’indépendence’”, Le Figaro, 17 October 2018, http://www.lefigaro.fr/politique/2018/10/16/01002-20181016ARTFIG00285-philippe-gomes-invite-du-talk.php.

[35] One senior French official noted that if the 2014 census results showing Kanak areas were overlaid on a map of the “yes” vote, the two areas would be identical: personal communication, January 2019. See Pierre-Christophe Pantz, “Le paradoxe d’un referendum historique…sans surprise”, Revue juridique, politique et économique de Nouvelle-calédonie 32 (December 2018), 35–45.

[36] “Les résultats définitifs” 2018.

[37] “Les résultats définitifs”, 2018; see also Pantz, “Le paradoxe d’un referendum historique…sans surprise?”, 44.

[38] Personal communication, Paul Néaoutyine, November 2017.

[39] French analysts review the effect of the outcome for the “common destiny” in Revue juridique, politique et économique de Nouvelle-calédonie 32 (December 2018).

[40] Yann Mainguet, “Liste du referendum: le haussariat dément et corrige”, Les Nouvelles Calédoniennes, 2 October 2018, https://www.lnc.nc/article/nouvelle-caledonie/politique/liste-du-referendum-le-haussariat-dement-et-corrige.

[41] Yann Mainguet, “63% de Kanak sur la liste référendaire selon les FLNKS”, Les Nouvelles Calédoniennes, 19 September 2018, https://www.lnc.nc/article/nouvelle-caledonie/referendum/politique/63-de-kanak-sur-la-liste-referendaire-selon-le-flnks.

[42] Recensement 2014, http://www.isee.nc/population/recensement/communautes. There are also 20.2 per cent “others”, which include mixed race (8.6 per cent) and “Caledonian” (7.4 per cent) in which some Kanak and/or islanders would inevitably fall (along with some Europeans). There are also small numbers of long-standing Asian residents (Indonesians 1.4 per cent, Vietnamese 0.9 per cent), nearly all of whom would be eligible to vote and who have tended to vote for loyalists in provincial elections.

[43] Section “Sous l’oeil des indépendantistes d’Europe et du Pacifique”, in “Affiche, drapeau, réseau: chacun sa campagne”, Les Nouvelles Calédoniennes, 31 October 2018, https://www.lnc.nc/article/nouvelle-caledonie/referendum-2018/politique/affiche-drapeau-reseau-chacun-sa-campagne.

[44] “Les résultats définitifs”, 2018”; personal communication, senior French adviser, February 2019.

[45] “Accord particulier: signature d’une declaration d’intention entre Wallis et Futuna, La Nouvelle-Calédonie et l’État”, Calédonie 1ère, 25 March 2019, https://la1ere.francetvinfo.fr/wallisfutuna/politique-signature-declaration-intention-entre-wallis-futuna-nouvelle-caledonie-etat-693322.html.

[46] See Carolyn Nuttall, “Conflict, Colonisation and Reconciliation in New Caledonia”, ANU Open Access Theses, 2016, https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/handle/1885/135770.

[47] Jean-Pierre Doumenge, “Au lendemain du referendum du 4 novembre”, Revue juridique, politique et économique de Nouvelle-calédonie 32 (December 2018), 20; see also Bastien Vandendyk, “Les enjeux du processus d’indépendance en Nouvelle-Calédonie”, Asia Focus 15 (Paris: Institut des relations internationales et stratégiques, 15 January 2017), http://www.iris-france.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Asia-Focus-15-Nouvelle-Cal%C3%A9donie-janv-2017.pdf.

[48] Relevé de conclusions, XVIIIme Comité des signataires de l’Accord de Nouméa, Paris, 14 December 2018, https://www.gouvernement.fr/sites/default/files/document/document/2018/12/xviiie_comite_des_signataires_de_laccord_de_noumea_-_releve_de_conclusions_-_14.12.2018.pdf.

[49] The process has been foreshadowed in the French Prime Minister’s statement at the outset of the official campaign, spelling out the procedures to follow in the event of either a “No” or “Yes” vote: “Les implications de la consultation du 4 novembre 2018”, Paris, October 2018, https://www.elections-nc.fr/referendum-2018/les-implications-de-la-consultation-du-4-novembre-2018.

[50] The difference between supporters of independence and of staying with France was 18 535 votes in an eligible electorate of 174,165, with 138,933 valid votes cast, and 33 066 abstentions: “Les résultats définitifs”, 2018.

[51] These will include 19 152 voters who abstained on 4 November in Southern Province, and 8470 Kanaks from Loyalty Islands: “Les résultats définitifs”, 2018.

[52] Personal communications, Noumea, 2017; and “L’Année 2019 va être plus décisive que le referendum”, interview with founding Accord negotiator Alain Christnacht, Les Nouvelles Calédoniennes, 23 October 2018, https://www.lnc.nc/article/nouvelle-caledonie/referendum-2018/politique/l-annee-2019-va-etre-plus-decisive-que-le-referendum.

[53] Emmanuel Macron, “Déclaration du Président de la République — Référendum de la Nouvelle-Calédonie”, 4 November 2018, https://www.elysee.fr/emmanuel-macron/2018/11/04/declaration-du-president-de-la-republique-referendum-de-la-nouvelle-caledonie-du-4-novembre-2018; leaked comments were reported prominently in New Caledonia’s only daily paper, in “Emmanuel Macron, selon le canard enchaîné: ‘Le “non” n’a rien de franc et massif’”, Les Nouvelles Calédoniennes, 8 November 2018, https://www.lnc.nc/breve/emmanuel-macron-selon-le-canard-enchaine-le-non-n-a-rien-de-franc-et-massif.

[54] “La ministre des Outre-mer tente d’éteindre la polèmique après ses propos sur la Nouvelle-Calédonie”, La 1ère, https://la1ere.francetvinfo.fr/ministre-outre-mer-tente-eteindre-polemique-apres-ses-propos-nouvelle-caledonie-667625.html.

[55] Jean Courtial and Ferdinand Mélin-Soucramanien, “Réflexions sur l’avenir institutionnel de la Nouvelle-Calédonie”, Paris: Rapport au Premier Ministre, 2013, https://www.ladocumentationfrancaise.fr/var/storage/rapports-publics/134000711.pdf.

[56] Alain Christnacht, Yves Dassonville, Régis Fraisse, François Garde, Benoît Lombriere and Jean-François Merle, “Rapport de la mission d’écoute et de conseil sur l’avenir institutionnel de la Nouvelle-Calédonie”, Paris: Rapport au Premier Ministre, 18 November 2016, http://www.outre-mer.gouv.fr/rapport-de-la-mission-decoute-et-de-conseil-sur-lavenir-institutionnel-de-la-nouvelle-caledonie.

[57] “Le Palika soutient l’indépendance avec partnériat”, Les Nouvelles Calédoniennes, 13 November 2017, https://www.lnc.nc/article/pays/politique/le-palika-soutient-l-independance-avec-partenariat, accessed 24 December 2018.

[58] Philippe Gomès, “Pour que continue à vivre le ‘rêve calêdonien ”, Colloque sur l’avenir institutionnel, University of New Caledonia, 18 November 2017.

[59] Relevé de conclusions, XVIIIme Comité des signataires, 14 December 2018.

[60] These are the so-called Article 27 (of the 1999 Organic Law) provisions which New Caledonia could have taken on at any time but on which local parties could not agree.

[61] Personal communications; and see Olivier Gohin, “Les suites du referendum calédonien — 4 novembre 2018”, Revue juridique, politique et économique de Nouvelle-calédonie 32 (2018), 8–11. It should be noted that successive French administrations, socialist and republican alike, as well as Macron’s En Marche, and Marine Le Pen’s National Front election platform, have committed to respect and implement the Noumea Accord, which would presumably include its referendum provisions.

[62] Emmanuel Macron, Discours du Président de la République à Nouméa, 5 May 2018, http://www.voltairenet.org/article201080.html.

[63] Macron Discours, 4 November 2018 and his leaked reported comments in “Emmanuel Macron, selon le canard enchaîné: ‘Le “non” n’a rien de franc et massif’”, Les Nouvelles Calédoniennes, 8 November 2018. He had also indicated in his 5 May 2018 Noumea speech that the referendum process was “creating a sovereignty within a national sovereignty” and that France would not be the same without New Caledonia.

[64] The most recent is Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs internal White Paper, “2030 French Strategy in Asia-Oceania”, August 2018. Others include Department of Defence, Revue stratégique de défense et de sécurité nationale, 14 October 2017, 27; 2013 Defence White Paper; Foreign and European Affairs Ministry, La France en Asie-Océanie: enjeux stratégiques et politiques, August 2011; the Economic Social and Environment Council, “L’extension du plateau continental au-delà des 200 milles marins: un atout pour la France”, Journaux officiels, October 2013; and three Senate reports: “La maritimisation”, Rapport d’Information No 674, 17 July 2012; “Colloque La France dans le Pacifique: quelle vision pour le 21e siècle?”, 17 January 2013; “ZEEs maritimes: Moment de la vérité”, 9 April 2014.

[65] France’s possessions include in the Pacific New Caledonia, French Polynesia, Wallis and Futuna and Clipperton Island; the French overseas Departments of Réunion, Guadeloupe, Guyana, Martinique and Mayotte; Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon, Saint Barthelemy, Saint Martin, and French Antarctic and Southern Lands.

[66] France’s Pacific territories contribute seven of France’s global 11.57 million sq km of EEZ, with France’s continental EEZ only 340 290 sq km. Jean-Yves Faberon and Jacques Ziller, Droit des collectivités d’outre-mer (Paris: Librairie Générale de Droit, 2007), 8. See also, The Economist, “Drops in the Ocean: France’s Marine Territories”, 13 January 2016, https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2016/01/13/drops-in-the-ocean-frances-marine-territories.

[67] Denise Fisher, “One Among Many: Changing Geostrategic Interests and Challenges for France in the South Pacific’’, Les Études du CERI No 216 (Paris, Centre des recherches internationales, Sciences-po, December 2015), http://www.sciencespo.fr/ceri/en/content/one-among-many-changing-geostrategic-interests-and-challenges-france-south-pacific.