Afghans went to the polls on 28 September, but preliminary results from the presidential elections, originally due for 19 October, were pushed back to 14 November, only to be postponed again. Officials from the Independent Election Commission (IEC) cited technical issues as the reason for the delay, without providing any details.

The continued impasse has placed three sensitive political issues in competition with each other: the elections, peace talks, and security operations against the Taliban.

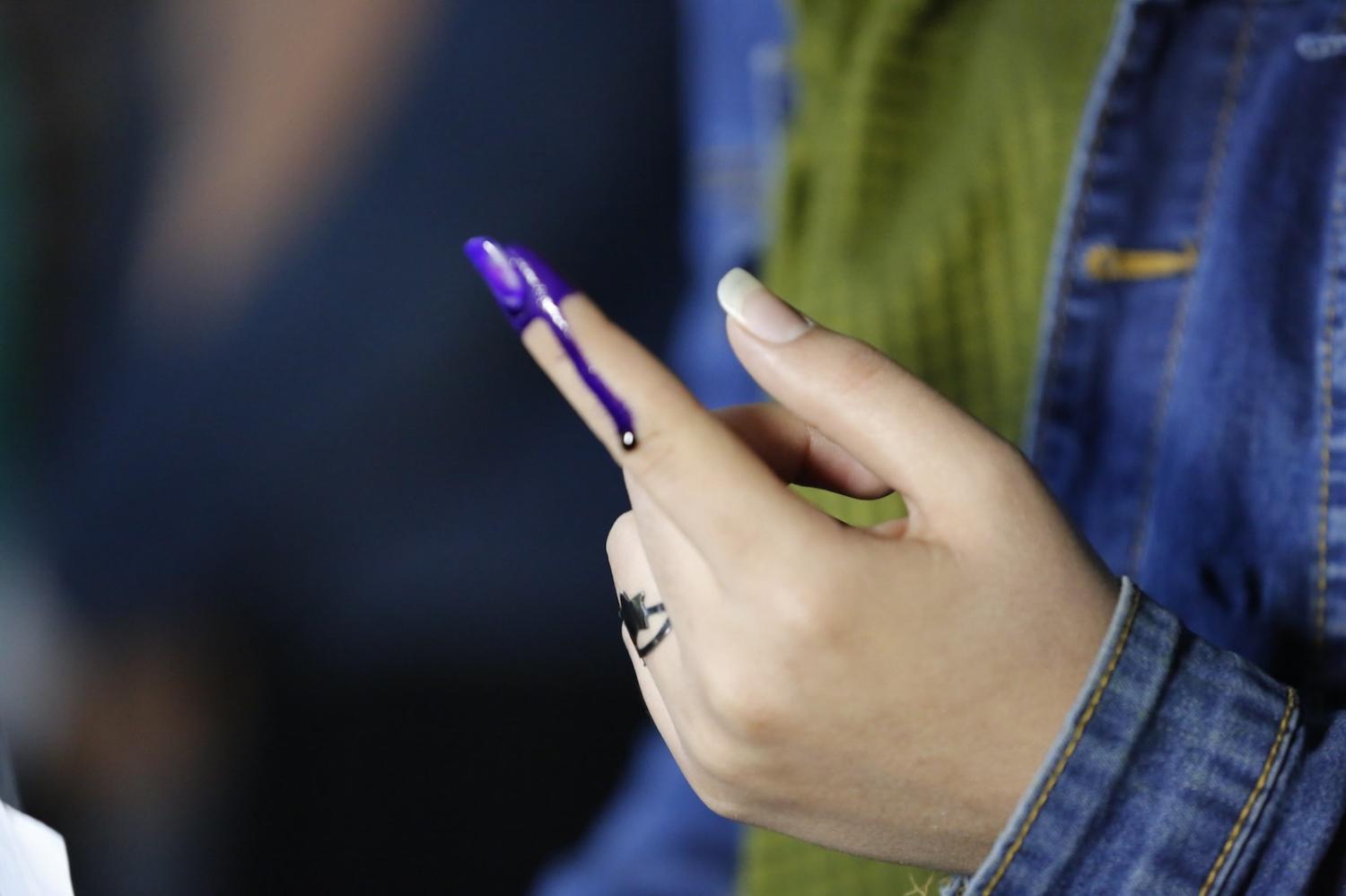

Presidential elections in Afghanistan (2009, 2014, 2019) have failed to inject much-needed accountability and political stability. One view is that elections undermine processes of political bargaining which are essential for political stabilisation, and derail elite cooperation. Because powerful actors want access to “rents” (i.e., state coffers and foreign aid money), they use fraud to renegotiate access to these rents. In turn, gross levels of fraud have led to heightened political uncertainty. It is clear from the IEC’s fluctuating official turnout figures from the 2019 presidential elections that vote counting is a problematic process. The commission dropped the vote count from 2.7 million to 2.1 million, and then 1.8 million votes, an indication it is struggling to separate valid votes from invalid ones.

The Taliban need not interfere in the dealings of the political elite, who are steadily eroding the state from within, which only serves to increase Taliban leverage in future peace talks.

The drop of almost a million votes has renewed fears of electoral fraud (in the form of voter suppression, rather than ballot stuffing). Whatever the election result, the record-low turnout will be used to question the legitimacy of whichever candidate attempts to form the next administration. This, in turn, has amplified the call for an interim administration, made by presidential hopefuls such as Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, a notorious former mujahideen commander. Other politicians have also called for jettisoning the elections in favour of an interim administration.

Why the calls for an interim government? Three reasons stand out.

First, political elites who have little or no chance at reaching the presidency or running successfully for parliament would stand to gain access to the state’s resources and institutions.

Second, relatedly, these elites seek to realign and renegotiate alliances, even if it comes at the expense of the state. By edging out competitors, they hope to ensure they maintain (or increase) their power.

And third, having a seat at the table would put them in a position to profit from any chaos that may follow a precipitous US military withdrawal from Afghanistan.

If there is no clear winner from the first round and a run-off vote is required, the demand for an interim government will only intensify. That means the IEC has the unenviable task of finding a formula that can simultaneously present a clear winner despite a record-low voter turnout, appease the main losing candidate and 13 other contenders for president, and make the entire exercise appear legitimate and transparent to the public, political elites, and the international community. But if a run-off vote must happen, Afghanistan will sit on a knife-edge as the incumbent, President Ashraf Ghani, and his main rival, Abdullah Abdullah, recalculate their positions amid calls for the dismissal of the National Unity Government and establishment of an interim administration.

The Taliban, meanwhile, can sit back and revel in watching rival politicians disrupt, weaken, and divide the political environment and the public. The chaos will only benefit them – the Taliban need not interfere in the dealings of the political elite, who are steadily eroding the state from within, which only serves to increase Taliban leverage in future peace talks.

Now that peace talks have gradually restarted between the United States and the Taliban, after US President Donald Trump called off a Camp David meeting in September, a key question is what type of government might an eventual peace settlement deliver? Proponents of the current constitutional system (and supporters of democracy) will argue that the state institutions built up since 2001 should survive the peace process. These supporters want democracy and the peace process to move forward without undermining one another. By contrast, the Taliban have no interest in maintaining the status quo and view themselves as a political entity that will take control of the state and recast it in its own image.

The Taliban have managed to sideline Ghani and exclude his administration from key peace negotiations in Doha, Moscow, and Beijing. They have also refused to engage in direct talks with the government in Kabul, regarding it as a puppet of foreign occupiers. But Ghani’s recent decision to release three imprisoned Haqqani network militants in exchange for an American and an Australian held captive since 2016 could potentially open the passage for direct talks. This, at least, is the hope of Afghan officials, but it remains to be seen whether the Taliban will view the move as a sweetener or irrelevant. Even if face-to-face talks do come to pass, a ceasefire, a power-sharing agreement (of any kind), and a negotiated end to the conflict are not on the horizon.

Elsewhere, Afghan security operations against the Taliban continue but have reached a stalemate. Afghan forces have recaptured a key north-eastern district from the Taliban after five years, but such advances are unlikely to have a strategic impact in increasing the political leverage of the government. Taliban fighters are capable of launching large-scale, coordinated attacks far from their traditional power centres in the southern part of the country bordering Pakistan – demonstrated on at least three occasions in September, when they assaulted the provincial capitals of the northern provinces of Kunduz, Takhar, and Baghlan. (These developments are not new, as the Taliban captured Kunduz for two weeks in 2015 and recaptured it briefly in 2016.)

What these attacks demonstrate is the Taliban’s military strategy of attrition warfare – each one has the effect of diminishing the already weak Afghan state. The Taliban’s leadership knows that international military forces will not stay forever, which they like to send reminders of by laying siege to cities. Another factor that stands out is their motivation to keep on fighting if the peace talks fall apart or fail to deliver a settlement with which they are satisfied.

What an acceptable peace settlement to the Taliban looks like is unknown, but what is broadly understood is that they will want primacy – not a secondary role to the current government they consider illegitimate or a future administration whose mandate will be record thin.