When Prime Minister Scott Morrison announced the establishment of the multibillion-dollar infrastructure development bank for the Pacific, the overriding sentiment was that this pivot to the South Pacific was designed to curb the rising Chinese presence in the region.

But is this renewed attention to Australia’s Pacific neighbours part of a long-term strategy, one of the aspirations in the 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper, or is it a knee-jerk response? If the motive is indeed to counter and diminish a Chinese presence, what happens if that threat is lessened? Would there be a return to an earlier chapter of reduced attention to the Pacific Islands?

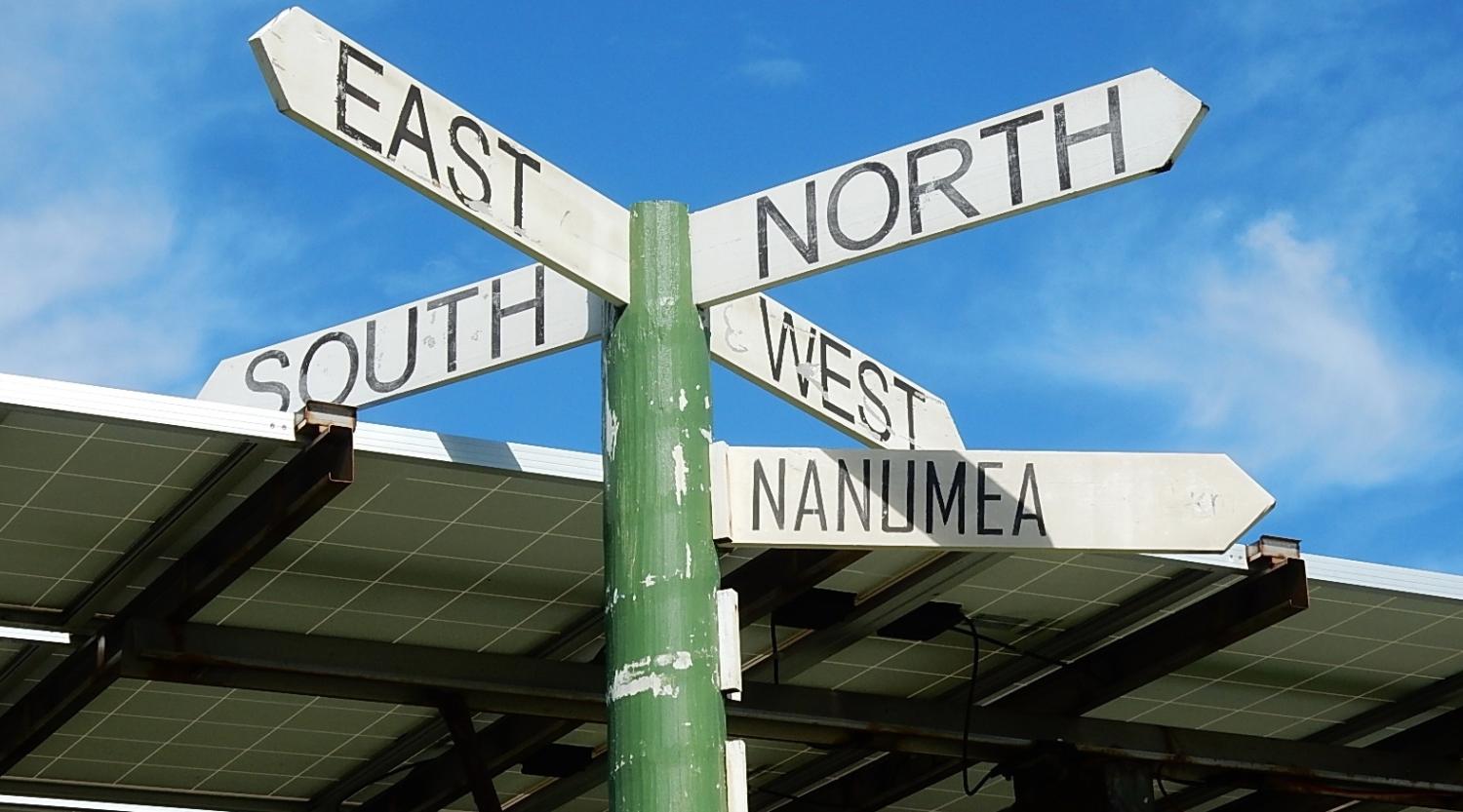

China’s meeting on the Belt and Road Initiative with Pacific Island leaders (within the margins of the APEC Summit last week) made evident that Australia’s position as a principal partner to the islands of the South Pacific has been threatened by China’s aspirations to be a dominant player in the region – a development which will not serve Australia’s strategic interests. It leaves Australia’s long-term relationship with its Pacific island neighbours at a crossroads.

The relationship needs to be fully reconfigured towards genuine partnerships and less towards convenient arrangements focused on Australia’s interests.

In practical terms, Australia interacts with the Pacific islands within three broad criteria; in a donor-recipient dynamic, as a security buffer, and as a regional partner.

As a donor, Australia still remains the largest bilateral donor to the Pacific islands. In providing aid though, the motive may vary between benevolence, exerting influence, and exporting the Australian “way of life.” Economic Diplomacy is hardly ever an altruistic undertaking and is instead the embodiment of “who pays the bills, dictates the conversation.” There is a strategic interest in providing aid, but the challenge is keeping the recipients happy and not creating an environment of simmering resentments.

The objective of exerting a type of soft power by exporting the Australian way of life also elicits resentment from a people with a long history and a vibrant culture. Attempts at influencing cultural changes through aid have very seldom worked.

An additional scenario to consider is the element of chequebook diplomacy. China or any other competing nation with an interest in the region could simply up its bid or fill any vacuums that are created if, and when, the aid package decreases.

For Australia then, a donor-recipient relationship with the Pacific islands may not be the most feasible option for a sustainable relationship going forward.

With respect to security concerns, the intentions behind the recent agreement with Papua New Guinea to build a naval base on Manus Island can be viewed as an activity to bolster Australia’s security interests, and not necessarily those of the Pacific Islands. The intended participation of the United States also reinforces that the security measures are directed at China. For many in the Pacific islands, their security issues are climate related, so it is very likely that they would prefer a strategy addressing the security implications of climate change – much like they sought at the UN’s Security Council in 2011 and again in 2018 – over a naval base. With their primary focus not being addressed, they will not be as committed to a Pacific defensive shield, even though this may also be to their benefit.

Australia has more regular contact with the Pacific Islands as a regional partner in agencies such as the Pacific Island Forum and the Pacific Community. These institutions are designed to bring greater coherence to the priorities of its members. But there still remains the question of the nature of these relationships and whose interests they serve. Australia as one of the main financiers of these organisations may have a bulk share in determining the priorities, but at what cost?

In recent years, the Pacific Island Development Forum – branding itself as “A Distinctive Pacific” – and the Pacific SIDS grouping at the UN in New York were established, as alternatives to the Pacific Island Forum. The various forums excluded Australia. Developments such as these signal to the international community that there is a divergence occurring between Australia and the Pacific Islands on regional and global priorities, and offer an opportunity for countries seeking to increase their influence in the region: Opportunities to which Australia has now found itself reacting.

The current pivot to the Pacific islands may have been as a consequence of China, but the gap that exists in the relationship between Australia and its Pacific neighbours remains. It may be that the relationship needs to be fully reconfigured towards genuine partnerships and less towards convenient donor-recipient arrangements, or reactionary measures on issues more focused on Australian interests.

Ultimately “the long-term partner” approach has a greater potential towards creating a Pacific security agreement, and the best option in countering any non-regional entity from being able to exert their influence in the region.