Australians will choose a new national government on 18 May in the context of two underlying trends: a record number of independents already now in office across the country and a political cycle that points to a Labor victory.

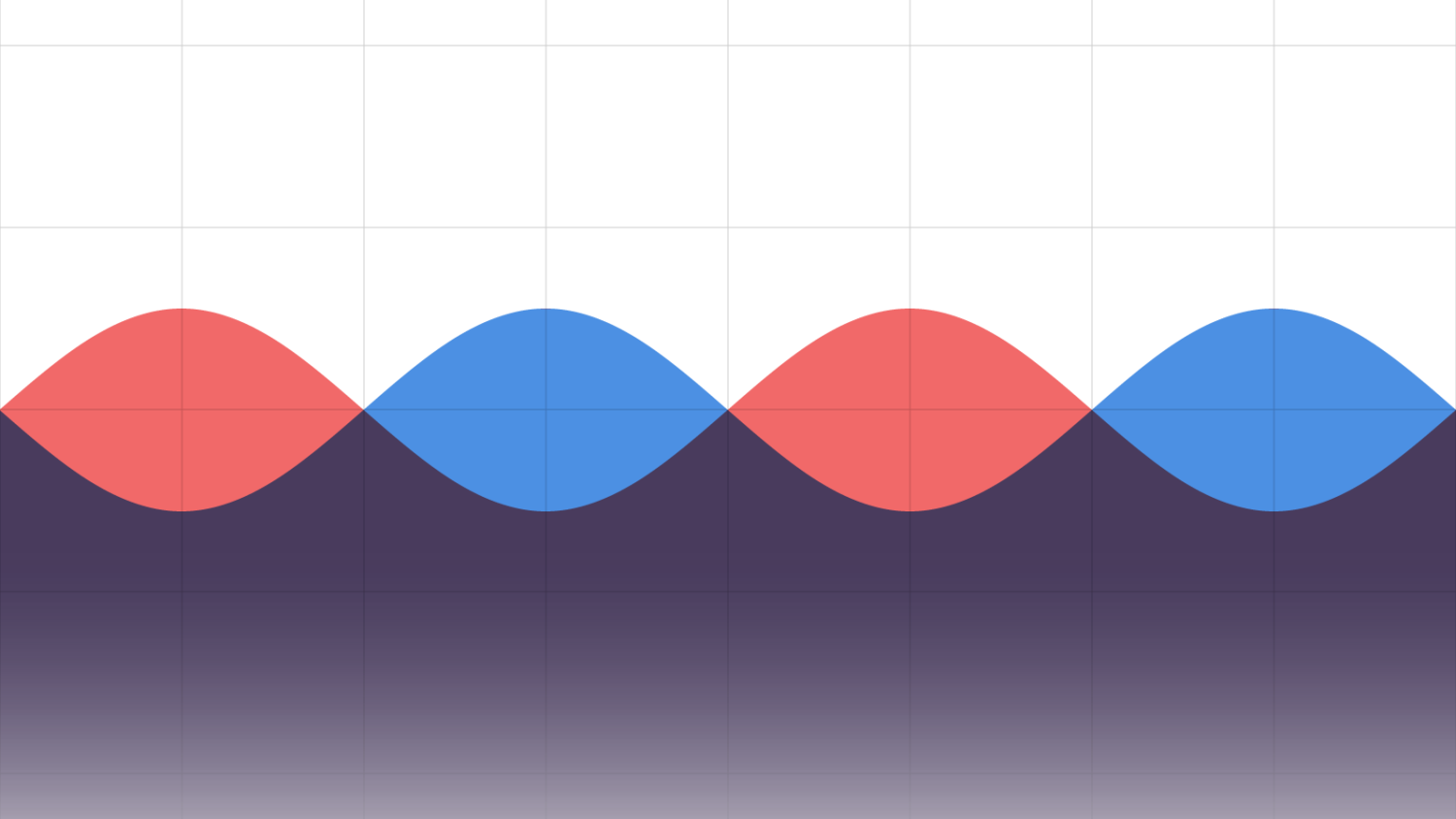

The below chart of elected members of parliament across the national, state and territory legislatures shows how the country has had a relatively clear cycle of political change over the past five decades. At the same time, it shows that there are now more than 100 independent or minor party representatives in those legislatures, which is record for the modern post-Second World War party system, and also arguably a record since nationhood a century ago.

Foreign observers of the election are likely to associate any change from the incumbent centre-right Liberal-National Party coalition government to Labor (as the opinion polls suggest) as a change in the national zeitgeist. That is not surprising since the national government controls foreign, defence, trade and immigration policy.

The Australian political cycle begins at the state level and then only flows through to the national level several years later at its more mature point.

But the chart shows that the Australian political cycle begins at the state level and then only flows through to the national level several years later at its more mature point. These cycles appear to be relatively independent of the economy as Australia has not had a recession for 27 years.

In the apparent new Labor cycle the number of Labor legislature members nationwide overtook the Coalition two years ago at the West Australian state election. But the Labor tally has been rising steadily for more than four years since the Victorian election in November 2014.

The shape of the last conservative cycle (2008–2017 coinciding with the leadership of prime minister Tony Abbott) lends support to the widely held view that Australian politics is becoming more intense and volatile due to factors that are found across the world, such as declining voter loyalty and the rise of digital media.

At their peak the Coalition parties held a greater share of seats nationally than during the previous conservative cycle associated with the leadership of prime minister John Howard, who is generally seen as the coalition’s most successful leader in recent times. But the Abbott cycle lasted less than nine years compared with an average of about 13 years for the last four cycles.

As a new Labor cycle appears to be under way it is interesting to note that the last two Labor cycles (associated with prime ministers Bob Hawke in the 1980s and Kevin Rudd in the 2000s) lasted longer than neighbouring conservative cycles. But the conservatives held a greater proportion of seats across the country at their respective peak, potentially making them more politically powerful.

The rise in independent or minor party legislature members passed the symbolic 100 point as a result of strong support for non-major party candidates at recent state election in Australia’s most populated state, New South Wales. But it was underpinned by minor party success at the recent Victorian state election and some losses by the federal Liberal party at the national level due to resignations and by-elections.

This new record reflects longer term trends including the rise of the Greens party, the success of moderate independents in normally safe conservative seats, and a flurry of small right-of-center parties such as One Nation and the Shooters, Fishers and Farmers Party. Analysts are split over whether the current election will see a return to two party polarisation, due to some sharp policy differences between the Labor and conservative parties or more minor party strength.

Nevertheless, the revelation that the independents or minor parties have crossed the 100 threshold will only add to alarm in the political establishment about difficulty assembling the majority governments, which have been the norm in the country’s traditional two-party system. Yet while non-major parties have won as much as a third of the primary vote overall at some recent elections, their share of seats is still much lower due to the way the electoral system works. Although they now hold a record number of seats across the country at 108, this is only 13% of the seats.

Australia has had two notable periods of previous non-major party success: the centrist Australian Democrats in the 1990s and the conservative and Catholic Democratic Labor Party in the 1960s. But they were largely contained to upper houses of Parliament, whereas independents and minor parties are now winning seats in lower houses where governments are formed, which means they can exert more power or simply disrupt government policy.

In an example of the rising concern, my Lowy Institute colleague Sam Roggeveen recently tweeted that this fracturing of the two party system has implications for Australia’s place in Asia.

The independents and minor parties do tend to have common views on some foreign policy issues, such as scepticism towards trade liberalisation and dislike for traditional realist foreign policy towards major neighbours, including China and Indonesia. However, on some specific controversial Asian policy issues such as capital punishment for drug traffickers, immigration and acceptance of refugees, the left and right-wing minor parties mostly tend to cancel each other out. This provides governments with more room to move on these Asia-related foreign policy issues.

The fracturing of the Australian electorate away from the major parties and the shortening of the political cycle are likely to make government more challenging, but it is nevertheless worth viewing this through an Asian prism.

Recent elections in Malaysia and Thailand have resulted in unwieldy multi-party governments, and India looks like sliding back that way in the current election. The Indonesian election has reduced the number of recognised parties, but a multi-party government will still be needed to pass legislation. And even in Japan the long-running conservative Liberal Democratic Party has to pay heed to the centrist foreign policy views of its Komeito coalition partner. Australia is far from alone.