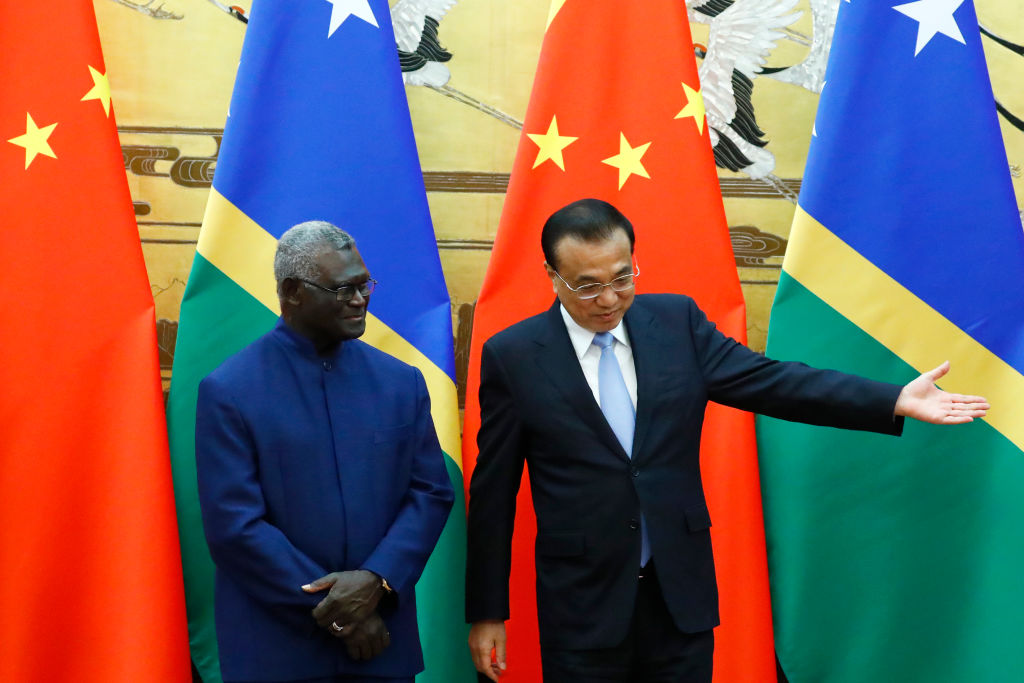

In September, the Solomon Islands government led by Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare severed its 36-year diplomatic relations with the Republic of China (Taiwan) and switched to the People’s Republic of China (China). In the months since, dissenting voices have kept bubbling up. Most prominently, on 26 November, the Solomon Islands Parliamentary Foreign Relations Committee submitted a report damning of the switch, calling for the government to instead deepen ties with Taiwan.

The committee’s recommendations to parliament stood in striking contrast with those of an earlier report produced by a bipartisan task force that had proposed Solomon Islands abandon Taiwan on the grounds of potentially huge economic and financial support China could render to the Pacific country, especially in the much-needed infrastructure sector.

The two reports provide a useful lens to observe the mixed responses to a rising China in Solomon Islands, and the Pacific at large.

The task force was appointed by the Solomon Islands cabinet and the report it produced was consequently political in nature. A senior Solomon Islands academic described the task force report as littered with inaccuracies, yet his main concern was not about the diplomatic shift but the capacity of Honiara to make such a decision based on the report. Politics in Solomon Islands is complex, marked by issues such as instability, the challenge of urbanisation, a lack of or minimal development in rural areas. Many of these issues combined to give rise to the civil conflict that took place in Solomon Islands in particular Guadalcanal from 1998 to 2003, after which the Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands intervened to bring back law and order, stabilise government finances, and help build state institutions.*

While politicians may change their positions to obtain economic and financial assistance from Beijing, the views of the general public about China is harder to shift.

But the dynamics of what are known as Constituency Development Funds (CDFs) are also crucial. The CDFs, an important part of the political economy in Solomon Islands, are funds that are given to members of the parliament for discretionary spending on rural development, the size of which having increased substantially over recent years. Central to the CDFs was the role and contribution of Taiwan – and now China.

Taiwan had held onto a relationship with Solomon Islands while having only limited resources at its disposal. Yet pressure on CDFs continued to grow, as national leaders sought to deliver development and services while also using the funds to cultivate a political power base. As a consequence, Taiwan could not handle the pressures that related to the politics of CDFs. This political dynamic stemming from the desire to grow the funds available for infrastructure and other spending appeared to be the subtext of the recommendation to switch to China in the task force report.

The task force was criticised for a lack of consultation, as indeed was the government’s decision making on the switch issue. By contrast, the Foreign Relations Committee provided a venue for public consultation on the switch issue while serving a function as an advisory organ to parliament. Indeed, the principal recommendation from the Foreign Affairs Committee was for decisions to be “placed on hold” until the committee’s report is considered by parliament.

Differences in membership of the two also mattered. Some of the task force members were known for their pro-China positions, while the Foreign Affairs Committee was led by Peter Kenilorea Jnr, deputy leader of the Opposition. The switch issue has become an outlet for the opposition and other stakeholders to express dissatisfaction with the government.

The Malaita provincial government’s firm opposition to the national government’s switch from Taiwan to China is an obvious example. Local premier Daniel Suidani has made clear that Malaita, the most populous island in Solomon Islands, does not support the switch. In October, a “Malaita Communique” was published, stating that the province “rejects the Chinese Communist Party-CCP and its formal systems based on atheist ideology”, and pledged to prevent “wilful and exploitive investors”. Such a position also resonates with views held by some senior Pacific politicians, such as former Tuvalu’s Prime Minister Enele Sopoaga. Malaita has also refused Chinese aid, concerned about debt risks linked to Chinese concessional loans.

Although China presently has an upper hand in the diplomatic wrestle with Taiwan in Solomon Islands, the controversies surrounding the switch suggests it is too early for Beijing to claim victory. The challenges are serious, whether they are objections from politicians or grassroots in Solomon Islands.

While politicians may change their positions to obtain economic and financial assistance from Beijing – now the second largest donor in the region after Australia, according the Lowy Institute Pacific Aid Map – the views of the general public about China is harder to shift. This is compounded by the geographical complexity of Solomon Islands, a nation scattered over 900 islands and with more than 70 languages. Many Solomon Islanders live in remote areas with limited outside contact. International relations are far removed their daily life and their knowledge of China is scarce, which make them easy targets of political influence or even manipulation.

The establishment of official relations between China and Solomon Islands is unlikely to substantially increase common knowledge of China for Solomon Islanders, thanks to the Beijing’s over-emphasis on contacts with the Solomon Islands national government, a practice notable in the other Pacific Island countries which have had diplomatic relations with China for decades. This places China in a disadvantage when compared with traditional partners that devote substantial attention to grassroots and civil society organisations in Pacific island countries.

The extent to which China delivers its pledges to Solomon Islands will directly affect its acceptance in the country. In November, The Economist magazine reported that China’s failure to pay a promised US $242,000 to each of the Solomon Islands parliamentary members for supporting the switch to China might trigger a no-confidence vote in the Sogavare government, as well as rebounding negatively on Beijing. How the switch issue continues to develop will be a test of China’s influence in the Pacific.

* This article was updated subsequent to publication.