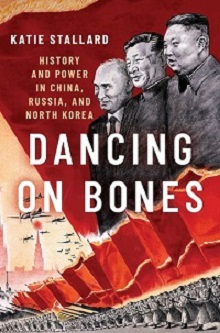

Book review: Dancing on Bones: History and Power in China, Russia and North Korea, by Katie Stallard (OUP, 2022)

In Piskaryovskoye Memorial Cemetery, in north-east Saint Petersburg, there stands a statue of Matushka Rossiya – Mother Russia. She grieves the sons and daughters who perished protecting her from Nazi invasion. Carved on the granite wall behind her are the words of poet Olga Bergholz. "No one is forgotten,” begins the couplet, which ends the first stanza. “Nothing is forgotten.” It is deeply moving. However, as Katie Stallard shows in her excellent book Dancing on Bones, it is also deeply misleading. History, in the hands of the calculating, is subject to constant revision. People and their causes are often forgotten.

One does not need to travel far to find a striking example. Stallard, Senior Editor for China and Global Affairs at the New Statesman, finished writing her book as Russian troops were massing on Ukraine’s borders. Between her laying down her pen and the book’s publication, Russia’s army invaded. Except, in the words and perhaps the heart of Vladimir Putin, Russia’s invasion was no such thing. Rather, it was a defensive operation designed to “de-Nazify” Ukraine.

To many, this was a nonsensical assertion. To others, a distant cousin of reality: the features are recognisable, but it is not the real thing. Stallard helps us understand. To generate domestic support for his invasion, Putin and his propagandists sought to rally Russian pride by invoking their heroic resistance against Nazi Germany. Nor was this the first time he had used this tactic. For almost a quarter-century, Putin has exploited the loss of Soviet life 80 years ago to repress and militarise Russian society – and steadily distance it from the liberal international order.

Putin’s is a specific form of a more general mechanism that Stallard describes in great detail throughout: the fashioning of historical memory into a potent political weapon that is then aimed at our enemies. Occasionally, as in the case of Russia, it is citizens of other nations who are the target. But, as Stallard shows, it is more often used to strengthen one-party rule at home.

Sometimes, the weapon of history is powered by pride or defiance, as illustrated by Russia. At other times, it is shame or humiliation. National Humiliation Day, marked to remember China’s “century of humiliation”, was recognised as an official holiday under the Kuomintang. Ideology, too, plays its part. Whatever the source material, the objective is the same: to strengthen political authority in the present. A core tenet of Chinese Communist Party propaganda today is that only it could have freed China from Japanese occupation and delivered the security and prosperity China enjoys today. Removing the stain of national humiliation is worth any price.

If Stallard's book has a weakness, it is that its focus is too narrow. That authoritarian rulers misuse history is a point worth making, especially if it is done in brisk prose and leavened with first-person reportage, as it is by Stallard. But the book would be better still if it compared the authoritarian’s misuse of history with the democrat’s. Perhaps it is unfair to criticise a book for telling one story and not another. However, as India, the United States and Poland teach us, the line that separates democracies and autocracies is not as thick as we believe. All offer up examples of how the raw material of the past – the pride, the shame, the humiliation – can be exploited in places where votes still matter.

Missing too, is a deeper examination of the line between coercion and conformity. There are many millions of true believers in Moscow, Beijing and Pyongyang. But what about the reluctant citizens who clasp their hands to their chests and sing their anthems just to get by, or just to survive? And what about the places where memories of war are sustained not from above, but from below? In the countries that feature in Stallard’s book, patriotism is self-preservation. But nations such as Australia and the United States need no such cajoling. Or what of the blooming of the poppy on every British chest on 11 November? Are these necessary reminders of the debts we owe our forebears? Or a pressure to conform we have collectively created for ourselves?

Such explorations would have been rewarding. Despite their absence, Stallard has written a fascinating, important and tragically timely book. As one keen student of history once warned, "the past is never dead. It's not even past." Nowhere is Faulkner’s aphorism truer than in Russia, China and North Korea.

The weaponisation of history has four victims. One is the free practice of the discipline itself. The next are the people living under the regime that fashions it into a weapon. Then there are the external targets of that weapon, such as the Ukrainians. The fourth class of victims are the men and women who gave their lives for the original cause. Grave is the crime of pressing them into posthumous service. Graver still is sullying their memories by turning them into ammunition for unjust wars.