In the four decades that have followed China’s initial stage of post-Mao “Reform and Opening Up”, the world has learned to expect great things from the Middle Kingdom’s centrally-planned economy. It has established itself as the low-end “factory of the world” and orchestrated an infrastructure-building boom of historic scale, which has lasted so long that many young adults in China know no other reality.

There are now a number of signs indicating trouble in the Chinese tech venture world.

However, as the manufacturers have begun to leave in search of cheaper labour and all the construction finally starts to slow, attention has shifted in recent years to what is being viewed by many as China’s next economic marvel: the rise of China’s internet and technology sector.

Leaping from relative global obscurity just a few years ago, China’s tech giants now seem to rival those of Silicon Valley, with nine of the world’s 20 most valuable internet companies calling the country home. In the second quarter of this year, Chinese start-ups received 47% of all venture funding, surpassing that of even North America.

For those concerned about the prospects of the end of Chinese economic miracle, the tech boom provides a reason to be optimistic – to believe that the decline of China’s expiring economic engine can be offset by the ascension of a new one, in which the world’s next technological revolution flows from China.

However, there are now a number of signs indicating trouble in the Chinese tech venture world, and that as impressive as its growth has been, it may not be immune to the troubles that plague the rest of the country’s economy.

Shaky foundations

Over the last 10 years, the transformation of China’s economy has seen debt rise so rapidly that total debt has now reached roughly 300% of its GDP. A significant portion is in household debt, but most remarkably, the majority is in corporate debt, as many companies must keep borrowing in order to stay afloat.

At the interest rates of these loans, just servicing the interest on the debt is roughly 18% of China’s total GDP. According to China’s National Bureau of Statistics, the country’s economy has been growing between 6–7% annually in recent years (although Chinese GDP data is suspect). That means that the cost of servicing the debt is roughly three times the rate at which the economy is growing.

The debt numbers in China could also be much higher than even those which are reported. This is because in recent years, China has seen a rapid expansion in “shadow banking”, off-balance-sheet loans made mostly by traditional commercial banks, often into riskier, less-regulated areas.

This rapid rise of lending in China over the last decade has increased global money supply more than the quantitative easing efforts of the US Federal Reserve, European Central Bank, and Bank of Japan combined. What is the result of this kind of debt expansion? Lots and lots of asset bubbles.

Most notable of these bubbles is housing, where apartments sit empty, being held as investments, while as a ratio of average wage to average apartment price, China’s major cities have some of the least affordable housing in the world. We’ve also seen asset bubbles in liquor, Tasmanian lavender teddy bears, and even illicitly-traded animal products such as ivory and rhino horn.

And of course, the tech bubble as well.

Discerning the substance from the vapourware

With so much cash in the economy, but with a heavy state direction and a lack of transparent financial systems, investing in China can be risky and uncertain. Chinese capital, therefore, can tend to be herd-like, based often on either subtle or not-so-subtle cues from the central government. This means that when the government states an objective to develop a certain industry, torrents of investment usually follow.

This is at least part of the equation making up China’s tech boom. The Chinese government has prioritised its internet and technology sectors, while at the same time restricting other forms of investment, such as real estate, or overseas investment.

The government is pumping money into the tech sector, as Christopher Balding, a former associate professor of business and economics at the HSBC Business School in Shenzhen and a Bloomberg contributor, puts it:

They are directing the herd, but also part of the herd as well.

This tech venture funding might now surpass North America, but it is far from clear how the reality on the ground can support this level of investment. China certainly has strong engineering and technical talent, but is unlikely to be on par with that of North America at this current moment. The same goes for managerial talent, venture investment expertise, corporate governance, or access to global consumer markets.

The Chinese Communist Party seems to be using the same approach to tech as they have to infrastructure development: top-down, centrally planned and directed. This model worked wonders for China, especially during the 1990s and 2000s, when there were plenty of low-risk, high-reward infrastructure development projects that needed to be made. This led to a great deal of waste and corruption as well, but there would also be a road, bridge, or skyscraper to show for it.

The same model is being applied to technology development, an area which is far less tangible. Waste and corruption is certainly evident in China’s tech boom, but it is not yet clear what else it will produce.

Indeed, there seems to be an abundance of cash, but a deficit in strong, well-managed tech firms in China. This leads to bad start-ups getting funded when they shouldn’t, and good start-ups being overfunded and overvalued.

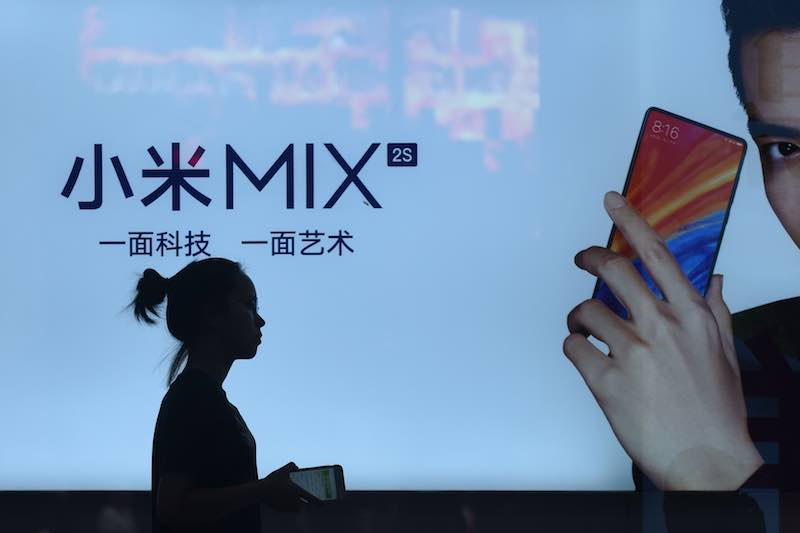

For the latter, take Xiaomi as an example. The smart-device maker, known as “China’s Apple,” was expected to be this year’s star Chinese tech IPO. The company, as well as some bullish analysts, expected them to go public with a US$100 billion valuation. At the time of IPO, however, Xiaomi shares hit the markets with a total capitalisation of only US$50 billion. At the end of last month, the shares were trading below the IPO price.

However, despite not yet living up to expectations, Xiaomi is still a legitimate company. This cannot be said for many Chinese tech start-ups that nevertheless still receive funding.

The Chinese Communist Party seems to be using the same approach to tech as they have to infrastructure development: top-down, centrally planned and directed.

Stories of well-funded companies with little technical talent and useless (or non-existent) products are common. Many of these firms are run by well-connected children of wealthy and powerful parents who made their wealth in areas such as real estate, manufacturing, and construction during previous decades. Their connections aid them in access to capital, yet the knowledge and expertise required to make products and run a successful tech company are not always a top priority.

Even if underperforming, China’s tech start-ups do serve a meaningful purpose. Youth unemployment is a major concern for the Chinese Communist Party, and a threat to both the economy and social stability. Having the nation’s young people work for lousy start-ups and tech firms is still better than them not working at all. As Balding explains:

In some ways, China’s tech boom can be seen as a government-funded job subsidy program.

As the credit tightens, Chinese tech gets squeezed

As debt levels in China approach a crisis point, its central bank has been attempting to curtail lending, walking the precarious tightrope of tightening credit while avoiding a major economic collapse. However, as the cash is getting increasingly difficult to come by, tech firms are starting to feel the pain.

The past three months have seen the once-hot “fintech” p2p lending sector fall apart almost entirely, as a credit crunch revealed many platforms to be operating as Ponzi schemes, leaving hundreds of thousands of small investors unable to withdraw their deposits.

Other vulnerabilities are also showing. After accounting for 60% of the world’s AI investment since 2013, many once-promising start-ups in the field may soon find that their days are numbered, with one of China’s top venture investors predicting that 90% of Chinese AI start-ups will encounter “great difficulty” over the coming two years, as the tightening of funding becomes “especially obvious this year”.

The growth of China’s tech industry over the past few years has truly been impressive. As liquidity begins to dry up, it will now become clearer how much of that growth was fact, and how much was pure fiction.