For many outside of the US, the country that is arguably the proudest of its democracy has a very odd way of electing its president. We can understand, just, why the founding fathers' obsession with the rights of individual states led to the Electoral College. Of course it seems strange that Hillary Clinton won more votes than Donald Trump, but didn't win the White House. But, as Georgetown University academic Jason Brennan wrote, we shouldn't confuse the machinery of democracy with democracy itself:

The Electoral College is an anti-democratic institution. From the perspective of the writers of the US Constitution, that’s a feature, not a bug. The entire point of the Electoral College is to serve as a check on democratic voting. The founders didn't trust the people to choose the most powerful person in the country (and now the world).

There were 51 popular elections on 8 November, one for each of the 50 states and one for the District of Columbia, and while Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton were on every ballot, the voters ticking, punching or clicking on those names were really voting for their state's slate of Republican, Democratic and Libertarian electors. This produces the 538 electors of the Electoral College, flesh and blood people who will cast their ballots for the president and vice president on 19 December. These are the ones that count. If, as expected, these electors follow tradition, their ballots will reflect the outcome of each state's popular vote. Each state's number of electors is equal to the number of Congressmen and Congresswomen it sends to Washington. The number in the House of Representatives varies from state to state according to population, the number of senators does not (each state has two), and herein lies the beauty of the system, according to supporters such as the conservative political commentator David Harsanyi, writing in the Denver Post:

....the Electoral College impels presidents and their political parties to consider all Americans in rhetoric and action. By allowing two senators for both Wyoming, with a population of less than 600,000, and California, with a population of more than 38 million, we create more national cohesion. We protect large swaths of the nation from being bullied. We incentivize Washington, D.C. — both the president and the Senate — to craft policy that meets the needs of Colorado as well as New York.

Of course, when the winner of the popular vote does not win the Electoral College, as has happened only five times - in 1824, 1876, 1888, 2000 and now 2016 - calls to change the system come thick and fast.

The latest count suggests Hillary Clinton has a popular vote lead of more than two million. This state-by-state breakdown (warning, you need a Google account to access) is truly fascinating and it's not surprising the results have generated a storm of what-ifs. This week in the Washington Post, for example, Christopher Ingraham moved one state border here, another there to shift four counties into neighbouring states and bump Hillary Clinton over the line in Wisconsin and Florida, thus delivering the 270 electoral college votes she needed for victory. Ingraham concludes:

Exact same votes, slightly different borders, radically different outcome: the capriciousness of the electoral college laid bare.

But if history is any guide, those pushing for change are on a hiding to nothing. In the last 200 years there have been 700 proposals introduced into Congress to change or axe the Electoral College. This reflects widespread and durable dislike for the system. As the Electoral College itself notes:

The American Bar Association has criticized the Electoral College as 'archaic' and 'ambiguous' and its polling showed 69 percent of lawyers favored abolishing it in 1987. But surveys of political scientists have supported continuation of the Electoral College. Public opinion polls have shown Americans favored abolishing it by majorities of 58 percent in 1967; 81 percent in 1968; and 75 percent in 1981.

But still it stands. The degree of difficulty to enact change is considerable as it would require a constitutional amendment. This generally needs to be first agreed to by two-thirds majority in the both houses of Congress and then ratified by three quarters of the states. So far, no proposal has got past Congress. And even if it did, it's hard to see that many states agreeing to changes, particularly the smaller ones that are generally thought to be favoured by the system as is. Notwithstanding the irony that a system designed to prevent a populist demagogue from becoming president has been trumped by Trump, the results of those 51 elections on 8 November are entirely valid. And come 19 December, the electors, despite pleas to do otherwise, will reflect that when they cast those ballots that will truly deliver Donald Trump the White House.

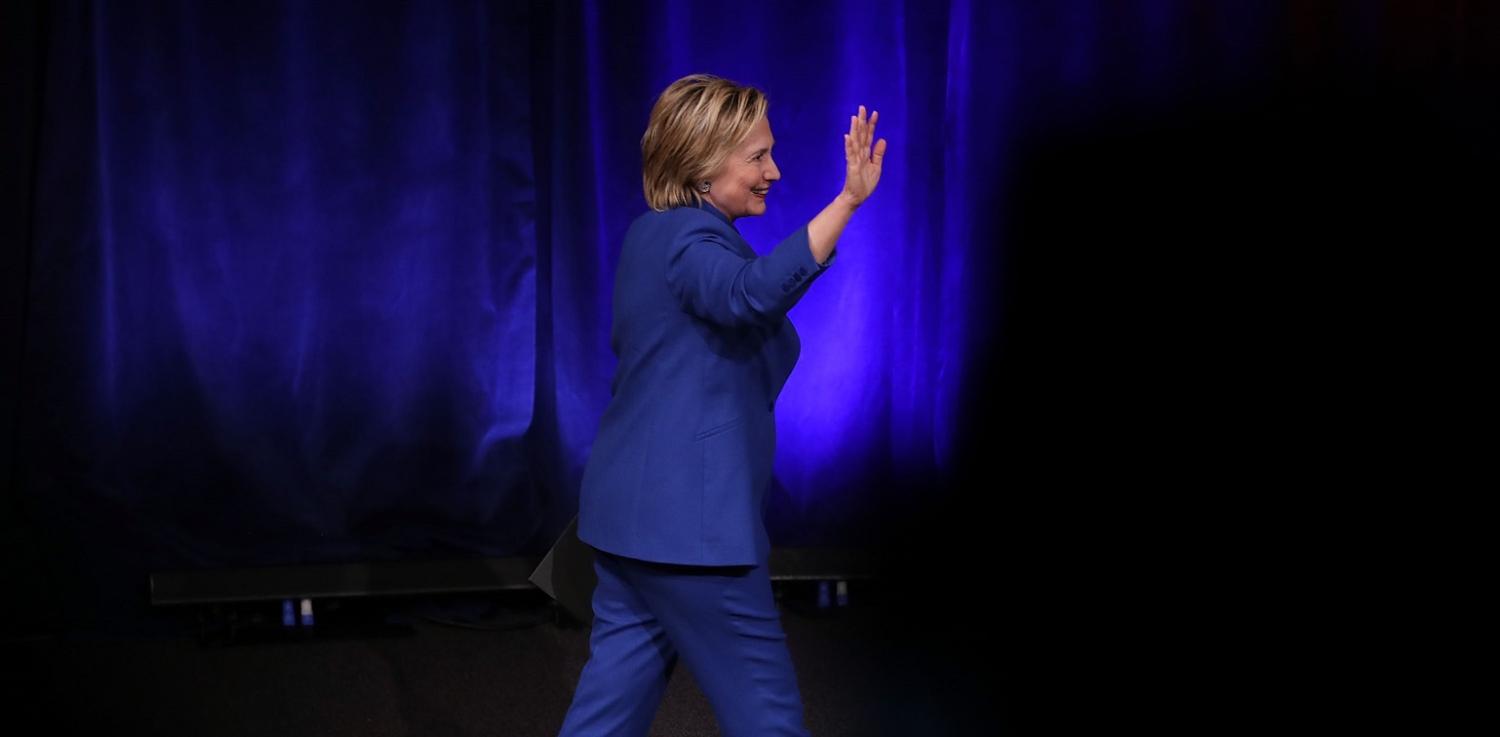

Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images