This year it is 25 years since Francis Fukuyama published The End of History and the Last Man – the span of a generation, as traditionally reckoned. The book, like the 1989 essay from which it grew, is more complex and sophisticated than the first phrase of the title suggests. Much of it is devoted to arguing for Hegel’s view of the primacy of ideas and ideologies over physical and especially economic factors in shaping history. Nonetheless Fukuyama’s big idea was simple and stark. In the oft-quoted line from the essay:

What we may be witnessing is not just the end of the Cold War, or the passing of a particular period of post-war history, but the end of history as such: that is, the end point of mankind's ideological evolution and the universalisation of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government.

Any really great phrase soon escapes the control of its creator and takes on a life of its own. By the mid-90s Fukuyama’s phrase came to stand for the much wider set of ideas, which became the model of the post-Cold War international order that still frames and constrains much Western policymaking and policy analysis today.

The heart of that model is the image of America as globally preponderant in every form of power. Although Fukuyama was generally careful to distinguish between Western liberal democracy in general and the American version, it proved hard to see this triumph of ideology as anything other than America’s triumph.

And Fukuyama’s focus on the primacy of ideology made it easy to slide from that to a more general judgement that there had been a radical shift in the global distribution of power. America came to be seen by the mid-1990s as unchallengeable economically, militarily, technologically and even culturally.

This preponderance appeared to create a global unipolar order in which other major powers would accept and support US global leadership, so it would face no powerful rivals in an era with no competing ideologies and when globalisation promised prosperity for all. And with America seen as so overwhelmingly powerful, who would risk taking America on?

This did not mean America would face no challenges at all to its leadership of the global order. But challenges would only come from relatively weak players at the margins of the global order – non-state actors and rogue states - not from the powerful states at its core. The 9/11 attacks therefore served to confirm the model.

So the wars and rivalries of the new century would be very different from those of the old – and fundamentally less demanding. Old-style power politics and great-power wars were passé. In the new American century, Washington would wield power and influence over the international system to a degree unprecedented since Rome at its height. Hence, the End of History.

Would that it were all true, but alas this is nothing like the world we live in. The model went wrong way back in the beginning, with Fukuyama’s focus on ideology. That diverted attention away from the two factors which have done most to shape today’s global order. Economic weight has shifted far faster than was realised, especially to China, and nationalism of a very old-fashioned kind persists, driving rivalry between major powers today very much as it did in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Meanwhile America has proved to be much less preponderant militarily than the old model assumed.

As a result, today’s international system is not framed by uncontested US primacy but by direct challenges to US leadership in three key regions (East Europe, East Asia and the Middle East) driven by nationalism and supported by local military strength (and in China’s case, massive economic weight). Power politics is back in a big way.

America would have to shoulder very big costs and risks to resist these challenges, including in some cases a small but not negligible risk of nuclear war. It has been far from clear under President Barack Obama that Americans were willing to do this. Under President Donald Trump it is quite clear that they are not.

So the model is wrong. And yet it remains the single encompassing idea behind mainstream American thinking on foreign and strategic policy, and Australia’s. From the Potomac to the Molonglo we still assume that we can and will achieve a rules-based global order premised on Western liberal democracy, led by America and supported by the world’s other great powers. And that leads us to misunderstand and mismanage the risks we really face.

How could our governing ideas be so at odds with the plain reality? Partly it is wishful thinking: we’d like it to be true, and thus easily convince ourselves that it is. But it is also, to be fair, the power of the End of History idea, and the fact that it has held such sway for so long.

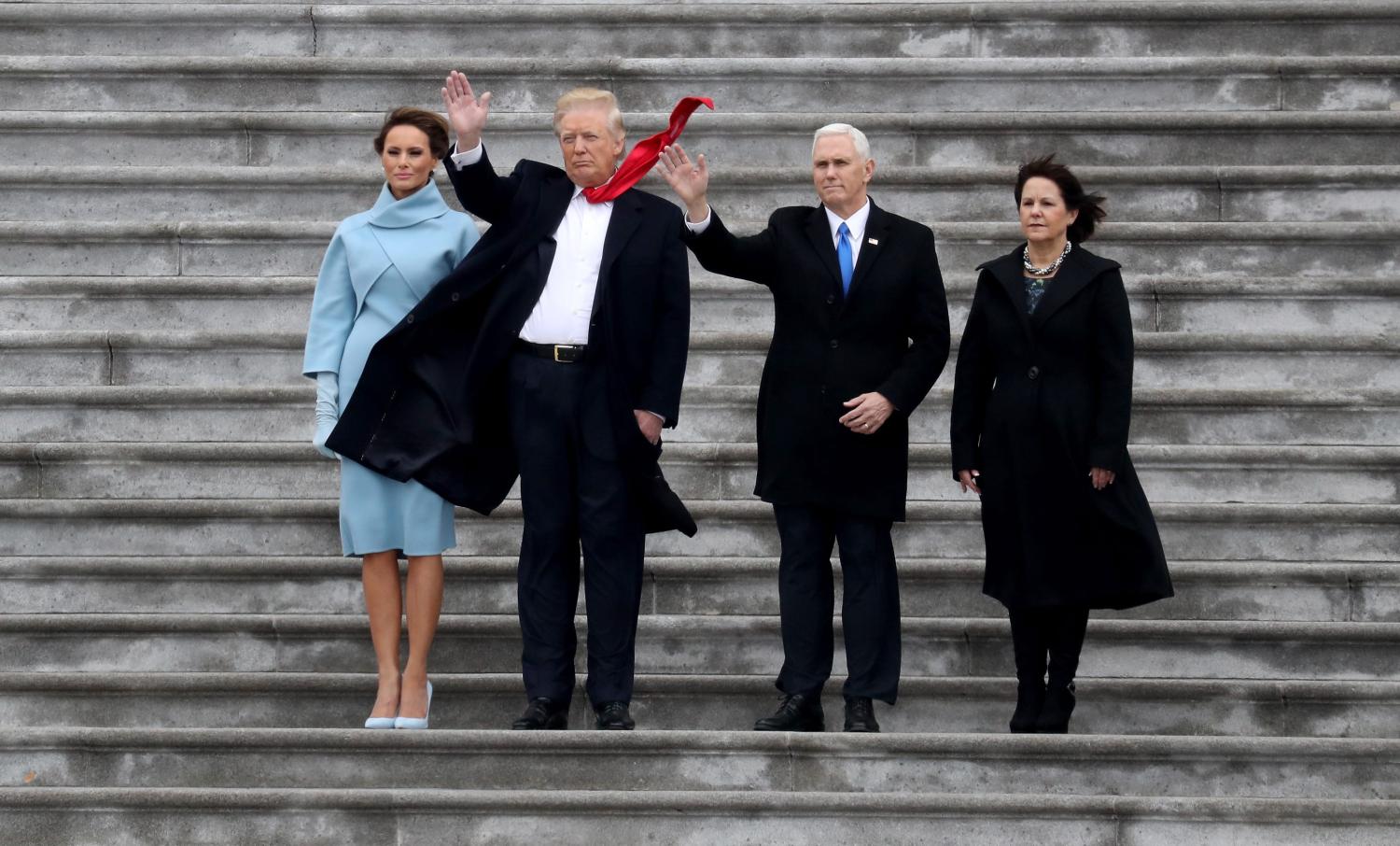

A whole generation has now passed since these ideas became our model of the world we live in, and a whole generation of political leaders, policymakers and analysts have grown up and pursued their careers under its sway. It has become hard to see the world in any other way, until events smash the old ideas completely. And that, of course, may be just what we are seeing as Donald Trump takes office.