We’re asking contributors to put together their own collected observations like this one – and as always, if you’ve got an idea to pitch for The Interpreter, drop a line via the contact details on the About page.

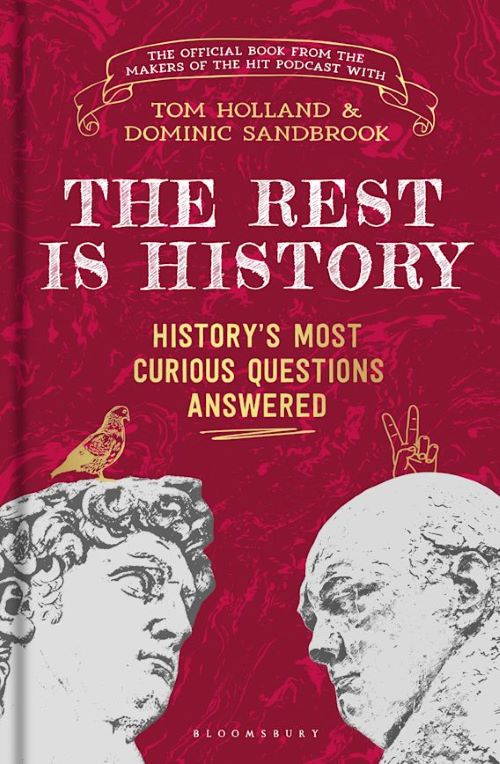

Reasonable people might well have been turned off revisionist history by Ridley Scott’s dull, flat, thin cinematic version of Napoleon’s life. An antidote lies close to hand, in the form of a book-length write-up of the popular podcast, The Rest is History.

Podcasts often resemble a bout of duelling banjos, with a pair of deliberately ill-matched commentators, sparring and sparking off each other like Britain’s Rory Stewart and Alastair Campbell, or Australia’s peripatetic Annabel Crabb and Leigh Sales. With the hosts for The Rest is History two distinguished historians turned podcasters, Tom Holland and Dominic Sandbrook, the effect is more seamless. Their task is to select bite-sized chunks of history to re-package.

Holland maintains that no episode in history is “so obscure, so unfashionable, so lacking in profile that people will fail to find it interesting”. Although he is surely wrong, Holland’s claim embodies the cheery, jaunty manner which informs The Rest Is History.

Holland and Sandbrook are playful as much as pedagogical, certainly never pedantic. The two of them exhume and dissect again topics from Atlantis to Alfred the Great, from Robin Hood to beavers and carrier pigeons. Vikings are used as a prompt for stories about “riches and rowing, pagans and Putin”. They try to intrigue listeners, now readers, with “top ten” lists, of celebrated eunuchs, what if’s, mistresses, and disastrous parties.

On the party front, who could not be captivated by a debauch starring not only a young Peter the Great but, in his retinue, 70 soldiers, a cook, a priest and a monkey? In the same vein, who could not re-visit Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury, after learning that he was the last British Prime Minister sporting a beard and the first to be able to turn on an electric light at home?

Australia is accorded a couple of cameos, one on the Somerton man, the other on Prime Ministers since John Curtin. A broad-church approach to issues leads the authors to award Bob Menzies the Order of both the American and the British Brown Nose.

Academic historians given to tut-tutting might complain that this sort of history lacks all those grand, abstract nouns beginning with “c”: coherence, context, continuity, even commitment. Lay readers might complain about an undue focus on Britain (mainly

England) and the classics (with Persians included as worthy foes of the Greeks, ones who “invented gardens – and paradise”).

Those cavilling would be mistaken, although Africa, India and China deserve more space in a sequel. Holland and Sandbrook pique listeners’ and readers’ interest and arouse their curiosity. After all, “inquiries” were Herodotus’ focus in the first attempt to write history. If the two historians manage to demonstrate, in their own beguiling and quizzical way, that learning history might be fun, surely they have done us all a service.

Alfred Einstein suggested that we make everything as simple as possible, but no more simple than that. Holland and Sandbrook heed that admonition, while also being determined to make their history as engaging, as whimsical and as enjoyable as possible.