On 2 November, the Government of India’s Press Information Bureau released two maps that show all of the former (but contested) princely state of Jammu and Kashmir as now comprising two entities: the Union Territory of Jammu and Kashmir and the Union Territory of Ladakh. Both belong to India. All people in them are Indians.

Singlehandedly, India has resolved the Kashmir dispute!

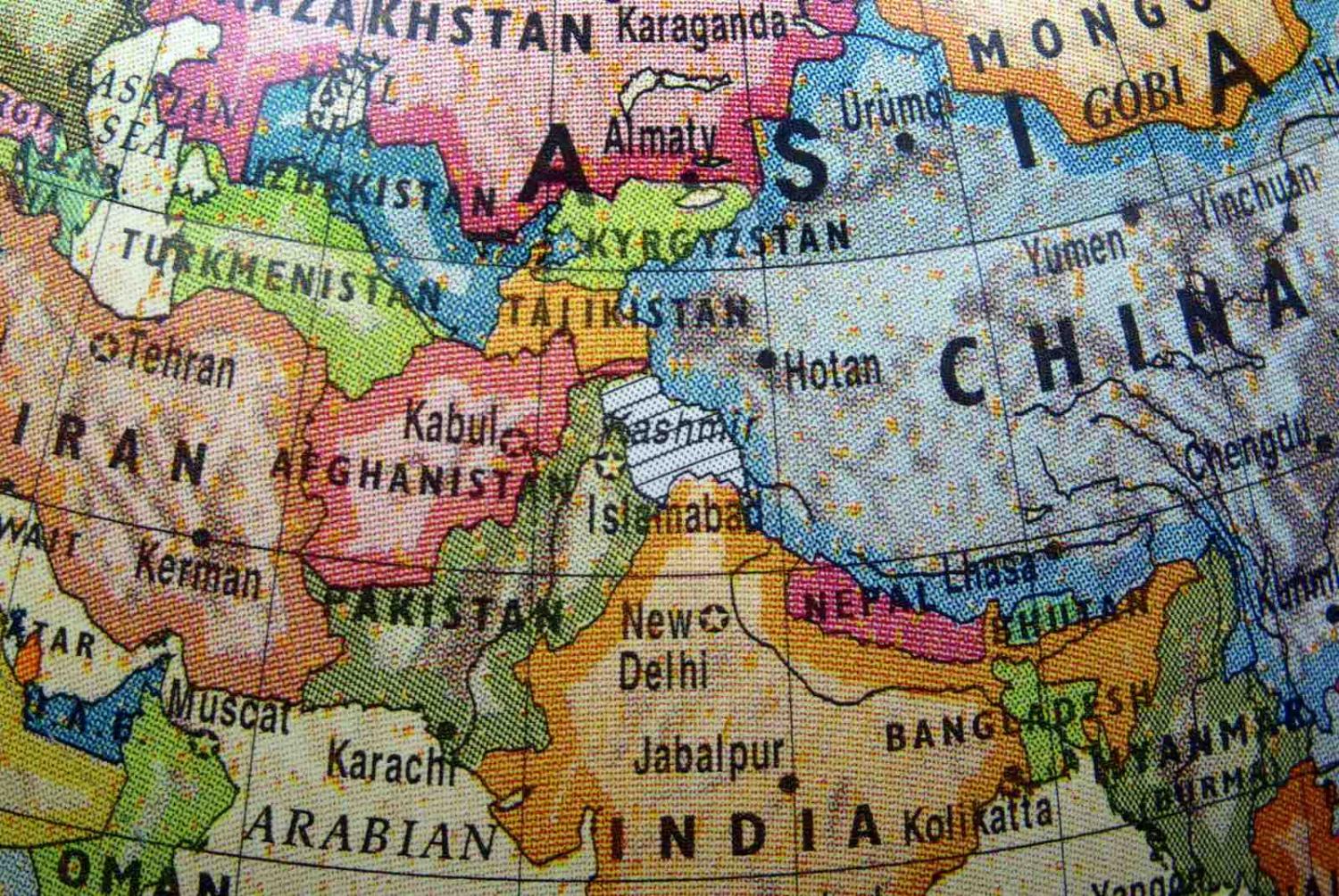

Except the Indian maps do not show Pakistan-administered Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan and Chinese-controlled Aksai Chin and Shaksgam. None of these four regions is under India’s actual control. For India, they simply don’t exist. The Union Territory of Jammu and Kashmir goes to the Pakistan border to include what would comprise Azad Kashmir; Ladakh extends to include the other three areas. Terms such as “Pakistan-Occupied Kashmir”, “China-Occupied Kashmir”, or “Line of Control” also don’t appear on the Indian maps.

These are not major mistakes or omissions. However, they reflect the fact that Indians are largely ignorant about “integral” parts of their nation outside their control.

Apart from creating two new Indian territories, these maps are not surprising: India has always shown all of the former princely state as being its own. Occupied or otherwise, all of it comprises “an integral part of India”, even though Indians have never set foot in the Pakistan- or Chinese-controlled parts.

For three reasons, these new maps are intriguing. First, on the Jammu and Kashmir map, the city Srinagar appears in a smaller font than the city Jammu, which might suggest that Kashmir is now less important than Jammu – a demotion many Jammuites and Indians would like, but which many Kashmiris fear and may resist.

On the Ladakh map, the term “People’s Republic of China” appears once, while on the Political Map of India released concurrently, it appears twice. In the Ladakh map, “People’s Republic of China” is written where Xinjiang would be, although this region is not specifically named, while Xizang is labelled “Tibet Autonomous Region” but with no obvious reference to it being part of the “People’s Republic of China”. Are the Indians trying to subtly tell the Chinese that the status of Tibet may be uncertain?

Second, the press release announcing the new maps states, “In 1947, the former State of Jammu and Kashmir had the following 14 districts – Kathua, Jammu, Udhampur, Reasi, Anantnag, Baramulla, Poonch, Mirpur, Muzaffarabad, Leh and Ladakh, Gilgit, Gilgit Wazarat, Chilhas and Tribal Territory.” However, neither the 1941 census of India nor the official “Administration Report of the Jammu and Kashmir State” of 1944 supports this exact structure.

In 1947, the small Chenani Jagir existed as a separate entity in Jammu Province. In 1947, Chilas (not Chilhas) was part of the Gilgit Agency in the large Frontier Districts Province, while no such “Tribal Territory” existed. Astore District was also nominally part of this large, strategically important province.

These are not major mistakes or omissions. However, they reflect the fact that Indians are largely ignorant about “integral” parts of their nation outside their control – in this case, the former Frontier Districts Province, much of which now comprises Gilgit-Baltistan. Few Indians have ever written specifically about this area or about Azad Kashmir.

Finally, the founder of Jammu and Kashmir, Raja (later Maharaja) Gulab Singh, an ethnic Dogra, must be turning in his ashes. (As a Hindu, he would have been cremated, not buried.) In 1846, he secured indefeasible (i.e., not forfeitable) title to Jammu and Kashmir from the British via the Treaty of Amritsar. This legitimised his control of areas already under his possession in Jammu, Baltistan, and Ladakh, which latter region included Aksai Chin.

To their later regret, the British also sold Kashmir (the Kashmir Valley), which they had won from the Sikh Empire in 1846, to the voracious Gulab Singh. Thereafter, he and his son consolidated the modern state of Jammu and Kashmir, which went on to become India’s largest princely state and one of its most prestigious and wealthiest.

From 1846 to 1952, Gulab and three of his descendants ruled Jammu and Kashmir. Significantly in 1947, this princely state had a 77% Muslim majority, which made some subcontinentals believe that the state’s final ruler, Maharaja Hari Singh, should accede to Pakistan. Instead, he chose India. For his efforts, the (Indian) Jammu and Kashmir Government officially ended Dogra rule in November 1952. The state, however, continued to exist.

Now, 173 years later, Maharaja Gulab Singh’s state is no longer. His legacy has been tarnished – surprisingly by a government that would be sympathetic to this Hindu’s personal achievements and religion. Apart from creating and dominating Muslim-majority Jammu and Kashmir, Gulab Singh captured Aksai Chin from the Chinese in 1842. This not only has provided India with its current claim to this Chinese-held territory, but also it made the Dogra one of the few Indians ever to expand India’s boundaries.

Seemingly, India is now doing the same using cartography. Expect protests by Pakistan and China.