Last Friday, the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) announced a 'breakthrough' in maritime boundary conciliation proceedings between Timor-Leste and Australia. The two parties 'reached an agreement on the central elements of a maritime boundary delimitation' and on a 'Special Regime' governing the development of Greater Sunrise and the allocation of resulting revenue.

While a number of issues remain, the PCA's announcement suggests that Australia and Timor-Leste have found a pathway for resolving the longstanding dispute about boundaries and Greater Sunrise.

Overall, news of the breakthrough in negotiations is a good sign. However, it is important to note that the agreement has not been finalised.

The context of the agreement

In April 2015, Timor-Leste initiated UN Compulsory Conciliation (UNCC) proceedings under Annex V of UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) to assist in resolving the long-running dispute. Despite the non-binding nature of the conciliation, both states appear to have entered talks in good faith. As part of the 'confidence building measures' that emerged from the meetings held in Singapore, both states agreed to terminate the 2006 Treaty on Certain Maritime Arrangements in the Timor Sea (CMATS). CMATS was intended to establish a framework for the joint development of the contested Greater Sunrise gas field (at one time estimated to be worth US$40 billion) and put a moratorium on permanent boundary maritime delimitation. As a quid pro quo, Timor-Leste scrapped two international legal proceedings against Australia.

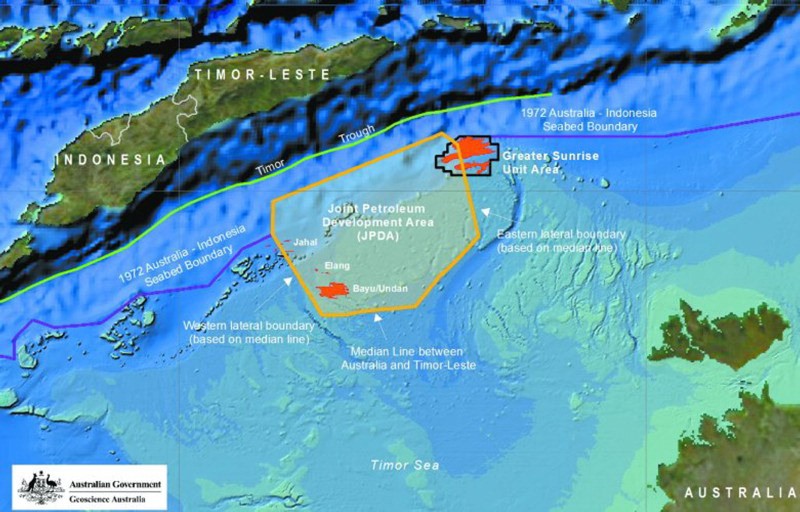

Over recent years, Timor-Leste's government has reinvigorated its pursuit of permanent maritime boundaries, arguing that they are necessary for completing sovereignty. The dispute with Australia was mainly over where boundaries would be drawn. Australia favours principles of 'natural prolongation', which provides it seabed territory extending to the Timor Trough. In contrast, Timor-Leste favoured a 'median' line, which is supported by contemporary international maritime law.

However, the key boundary for establishing possession of Greater Sunrise is the eastern lateral. The line preferred by Australia (which would place roughly 80% of Greater Sunrise in Australian waters) is based on principles of 'simple equidistance'. Timor-Leste claimed that the eastern lateral boundary should be located substantially to the east, which would place Greater Sunrise in Timor-Leste's possession.

A negotiated settlement

As I wrote in February, the most pragmatic course of action for resolving the dispute would be for Australia and Timor-Leste to compromise though bilateral negotiations based on median line principles.

An expedient negotiated settlement with Australia was in the interests of oil dependent Timor-Leste. The hydrocarbon revenues from the shared development in the Timor Sea are projected to disappear sometime in the early 2020s. A prolonged legal battle through international courts could have been highly problematic for Timor-Leste's economic future, and potentially required Indonesia's participation.

One commentator suggested that Timor-Leste's Greater Sunrise claim was based on UNCLOS, but that it ultimately accepted a 'lesser deal' because of its urgent need for gas revenues to stave off economic collapse. But UNCLOS provides little guidance on the placement of the eastern lateral boundary beyond demands for equity. Timor-Leste's claim was supported by a legal opinion commissioned by Petrotimor, an oil and gas company with a vested interest in shifting the line eastward. Timor-Leste's 'compromise' needs to be understood at least partly as resulting from the fact that its ownership claims over Greater Sunrise were legally dubious, a fact compounded by the recent PCA ruling in the South China Sea dispute between China and the Philippines.

As for Australia's decision to compromise, the termination of the CMATS made it difficult to avoid boundary discussions while simultaneously defending the primacy of the 'rules-based order' and imploring China to uphold the South China Sea PCA ruling. Additionally, it's also in Australia's interests to enhance Timor-Leste economic viability rather than risk an aid-dependent state on its doorstep.

A key question leading into this negotiation was whether Timor-Leste would be satisfied with permanent maritime boundaries that would only give it part of Greater Sunrise, or whether it would go for broke and refuse to settle for anything less than all (or most) of Greater Sunrise. Timor-Leste had reinvigorated its pursuit of permanent boundaries after its arguments for a pipeline failed, and reoriented its foreign policy to say that delimitation was 'the only acceptable solution' to the dispute.

It's clear Timor-Leste has compromised on its eastern lateral boundary claims. What this means for the division of resources and the development plans of Timor-Leste remains unknown. A significant question mark hangs over the future of Timor-Leste's planned pipeline to the south coast and its mega development project, Tasi Mane. More information should come to light in October following the finalisation of the agreement and consultation with various stakeholders.