The Lowy Institute has released an updated and expanded 2017 Global Diplomacy Index, which now maps and ranks 60 of the world’s most significant diplomatic networks. For the uninitiated, the Global Diplomacy Index is an interactive map that plots around 7000 individual embassies, consulates and other representations in over 700 cities across the globe.

The expanded Index adds the diplomatic networks of 17 Asian nations to the original set, which covered all 42 countries in the G20 and Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. Latvia is also a new addition, having last year acceded to the OECD. As with the original, users can view the global map of networks, select and view individual country networks on the map, prepare side-by-side comparisons, as well as see diplomatic representations city by city. The entire database is available for download through the site, as is the earlier 2016 version.

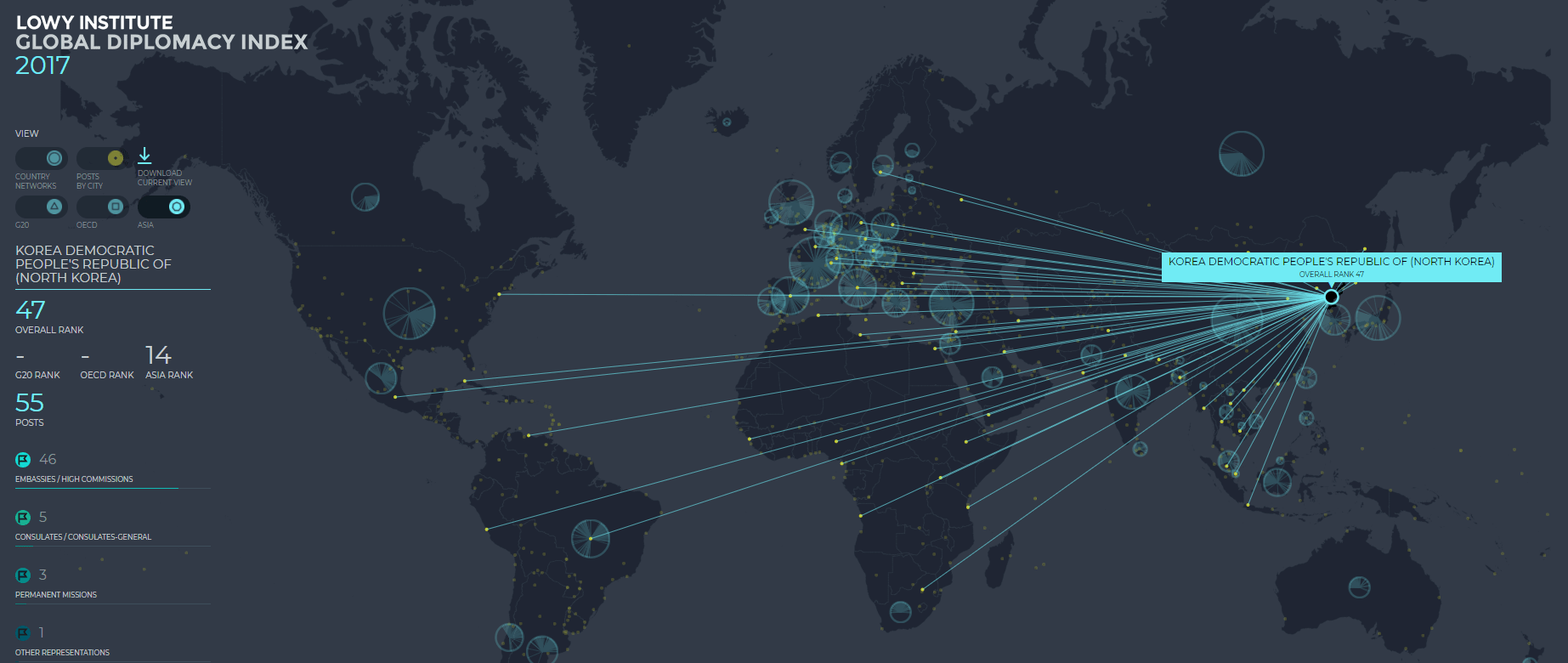

One of the fascinating things about the 2017 Index (and there are many: check out North Korea’s network, for example, which Alex Oliver and Euan Graham have written about for BBC) is that far from cataloguing the demise of the bricks-and-mortar embassy as the shopfront of diplomacy, the story the data tells is that the institution appears to be holding up.

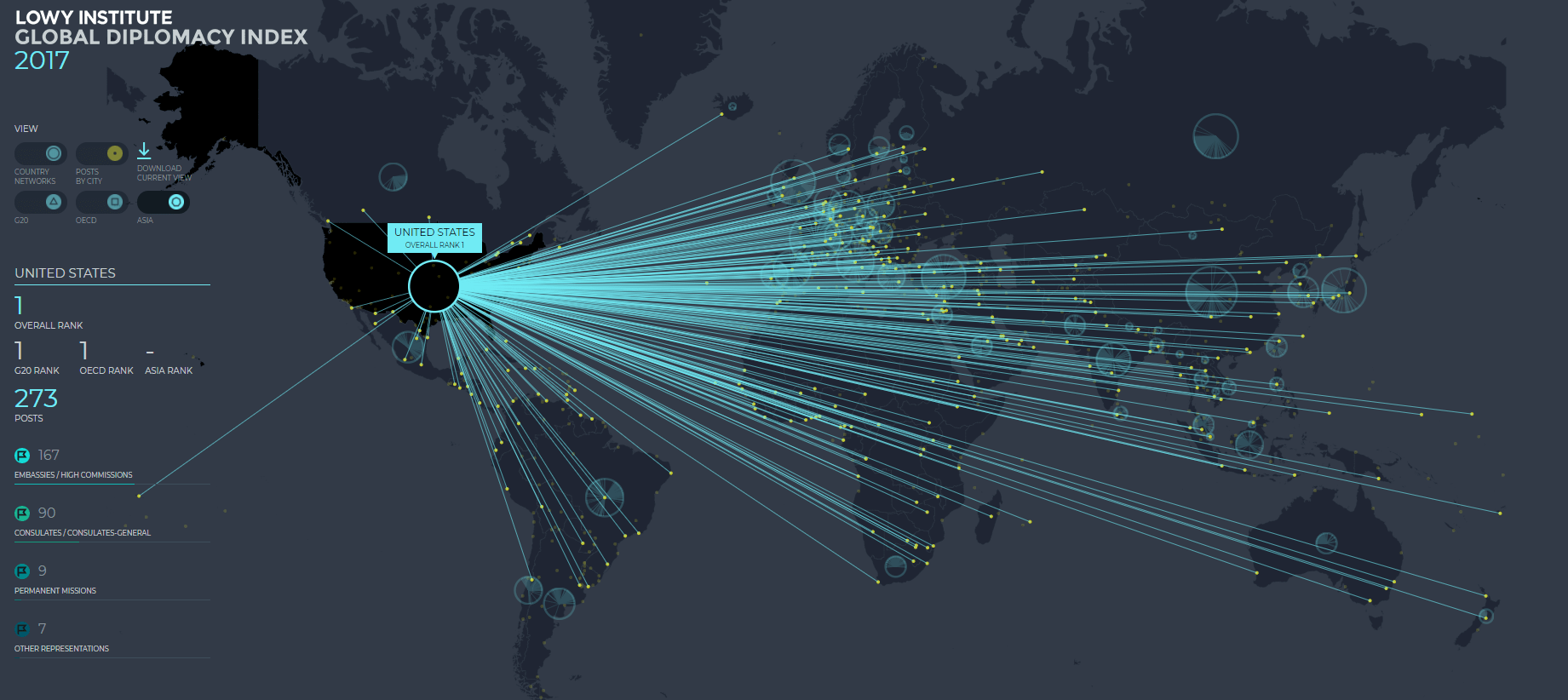

Two years ago, amid fervid enthusiasm for conducting world affairs on social media, and the conviction that digital diplomacy would displace more traditional forms of inter-state transactions, there was much speculation that the embassy was a thing of the past. The US foreign service especially has been assailed on all sides and found wanting, criticised as slow to adapt to modern communications and the digital revolution. It is the preserve of the ‘pale, male and Yale’. It struggles to operate under heightened security risks. It doesn’t help the cause of diplomacy that fully one third of 214 ambassadorial positions of the US, the top-ranked diplomatic power, are vacant, while populist politicians denounce government officials as deep-state ‘elites’.

Despite these challenges, the 2017 Global Diplomacy Index demonstrates that diplomacy as an institution is adapting and surviving. Few diplomatic networks have shrunk in the last two years: only 8 of the original 42 countries in the 2016 Index have reduced their footprint.

Twenty of the networks actually grew, even though budgets of foreign ministries across the globe have been consistently tight since the financial crisis. Hungary has increased its footprint by almost 10%, Turkey is eyeing new opportunities to extend its global presence, and Australia has enjoyed what our foreign minister has dubbed ‘the single largest expansion of Australia’s diplomatic network in over 40 years’, adding six new posts in the last two years.

In this year’s index, the US still has the top ranking with the largest diplomatic network of 273 posts in 176 countries.

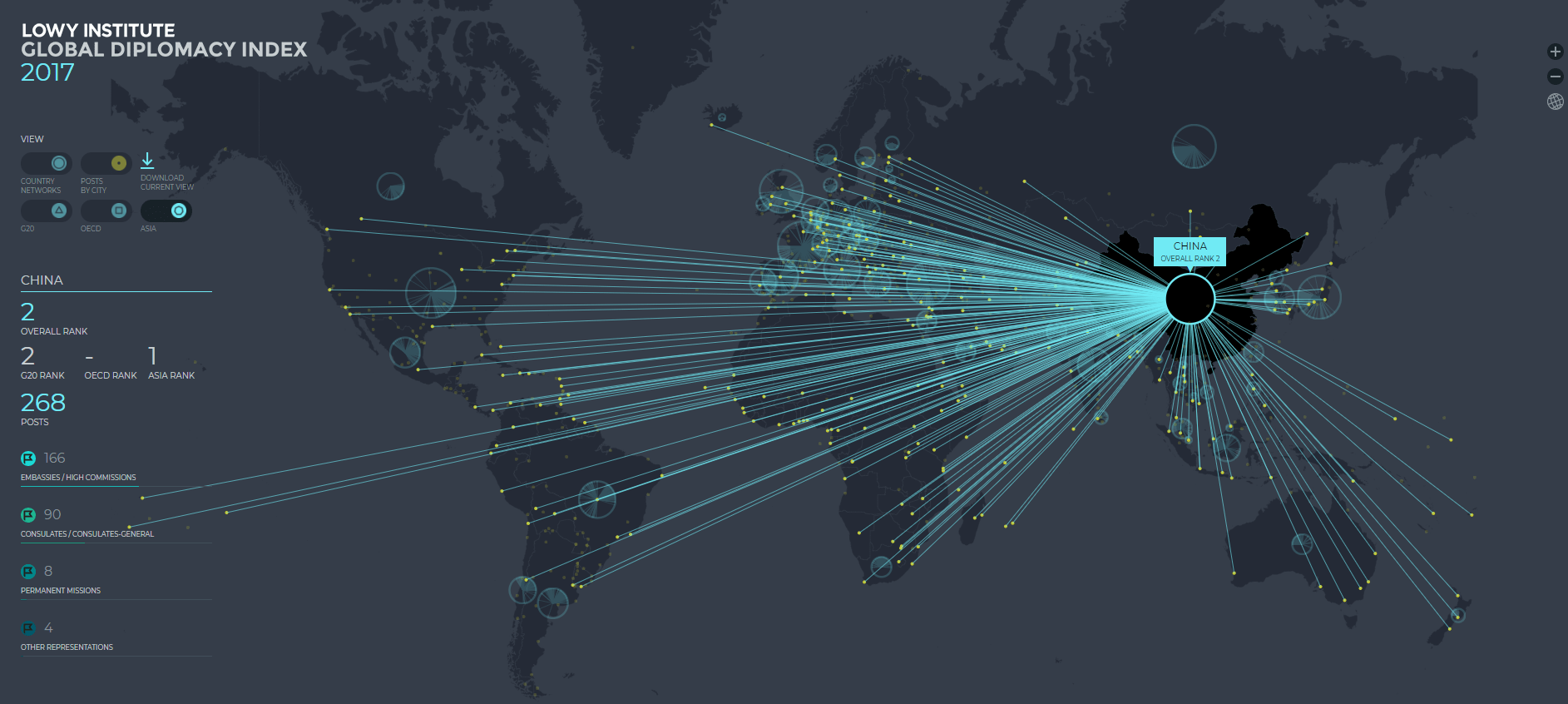

China (last year at third place) has climbed to second, adding ten new embassies or consulates since 2016 - in Central Africa, Central America, the Caribbean, the Pacific and Central Asia. China’s ascent has relegated France to third place, even though the French network remained intact. Russia is in fourth place, as it was in 2016. Japan is fifth, marginally ahead of Turkey, the United Kingdom and Germany, all of which are separated by a mere five posts.

Some countries don’t and won’t need saturation diplomatic coverage. Our research on Singapore, for example, shows that it has a small network of 49 posts in only 28 countries. But that is probably because it is exceptional in other ways: it is the world’s second largest port and one of the most highly connected trading nations of the globe.

Unlike Singapore, the majority of the world’s nations still need to maintain extensive diplomatic networks. They send envoys to learn and understand the unique conditions in each country, develop workable relations with authorities, navigate legal regimes and cultivate positive attitudes towards their own nation. They work hard to shape foreign relationships to bolster security and prosperity at home. They are also adapting to the challenges of the modern era, even if slowly: diversity is increasing, and foreign ministries have got a far better grip on working in a digital world.

Few predicted the upheavals the world has experienced this century. The usefulness of diplomacy as a tool of statecraft in addressing those upheavals has been questioned. Yet our research for this Index indicates that the world’s significant diplomatic networks remain largely intact.

You can view the full Index below.