South Korea has denied refugee status to the hundreds of Yemeni asylum seekers, most of whom are male, that arrived in Jeju in the first half of 2018.

Public opinion in South Korea remains largely negative to refugees more broadly, as seen in the backlash in 2013 to becoming the first country in the region to provide protection for those seeking asylum.

The arrival of the Yemenis was unusual. Other than North Koreans, who South Korea automatically grants citizenship once registered, South Korea is rarely viewed as a destination for those seeking asylum and only began accepting refugee applications in 1984. According to data from the Ministry of Justice, of the 20,974 completed applications from 1994–June 2018, only 849 (4.05%) were accepted as refugees, with another 1,550 (7.40%) given humanitarian status short of refugee. The South Korean refugee rights NGO NANCEN reports that only 1.5% of applicants in 2017 were granted refugee status.

However, as humanitarian crises in the Middle East strain the ability of neighbouring countries to absorb the influx of refugees, and public opinion about refugees sours in Europe, asylum seekers increasingly must travel greater distances in the hope of a host country. For example, by October of 2016, Japan only accepted six Syrian refugees and of the 20,000 asylum applications received in 2017, Japan accepted 20.

Many of the Yemeni asylum seekers in South Korea first travelled to the Muslim-majority country of Malaysia, which provides for three-month visa-free visits. But as a non-signatory to the 1951 UN Convention on Refugees, Malaysia appears unwilling to provide refugee status.

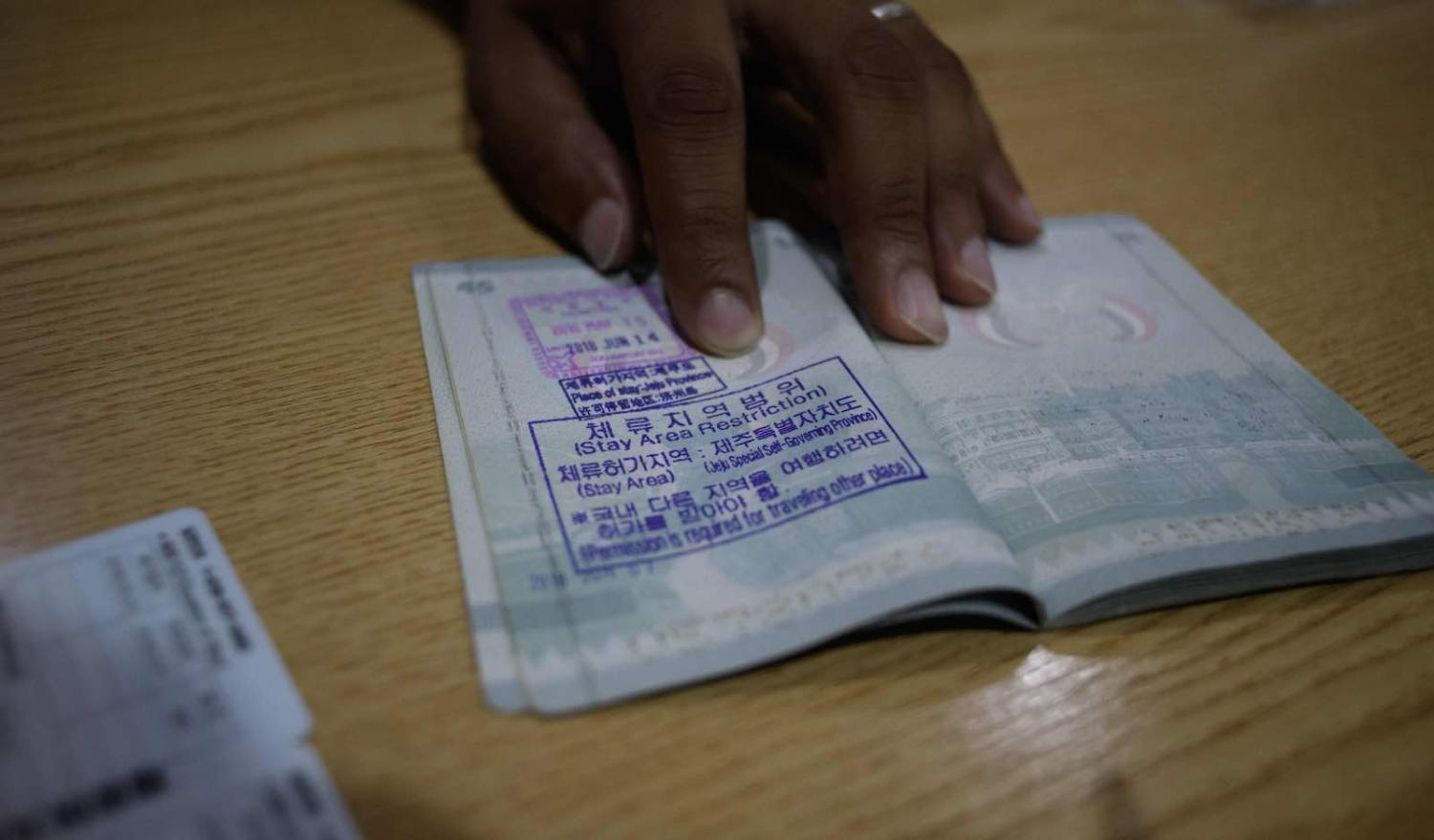

To further complicate matters, the visa-waiver program to Jeju island, intended to boost tourism, inadvertently gave Yemenis an incentive to attempt to travel to South Korea, exacerbated by direct flights from Kuala Lumpur starting in December of 2017. The visa-waiver program allowed Yemenis to come to Jeju, although not to anywhere else in South Korea.

Public opinion in South Korea remains largely negative to refugees more broadly, as seen in the backlash in 2013 to becoming the first country in the region to provide protection for those seeking asylum. Public opposition to accepting the Yemenis included 700,000 signatories to an e-petition to President Moon Jae-in’s office, with earlier surveys suggesting about half of the Korean public opposed granting the Yemenis refugee status. Earlier this year, nearly 1,000 protesters gathered in Seoul claiming the Yemenis were “fake refugees.”

Experimental work suggests that how refugees are presented influences public support. For example, research on Taiwanese public opinion finds that support for accepting Syrian refugees declined when the proposed number of resettled refugees increased, with no effect seen when emphasising their religion. Meanwhile, research on American public views suggests greater support when it is emphasised that most refugees are women and children.

To evaluate Korean perceptions of Yemeni refugees, we surveyed 605 South Koreans in the middle of November 2018 via a web survey conducted by Macromil Embrain, using quota sampling based on gender and province. We wanted to see to what extent three factors influence perceptions of the Yemenis: their total number, their number in relation to the number of Yemenis who have fled their country, and their religion. Respondents were randomly assigned to one of five versions of a prompt regarding whether Korea should accept the refugees (italics added for emphasis here). The statement put in Version 1 was used, with subsequent information for each version as follows:

- Version 1: The civil war in Yemen has created an international refugee crisis. Some claim that as a humanitarian crisis, it is the duty of other states to take in refugees. Others claim that taking in refugees creates a potential security risk.

- Version 2: Statement, plus: Approximately 500 Yemenis have arrived in South Korea in 2018.

- Version 3: Statement, plus: Of the approximately 300,000 who have fled Yemen, approximately 500 Yemenis have arrived in South Korea in 2018.

- Version 4: Statement, plus: Approximately 500 Yemenis have arrived in South Korea in 2018. Most of these arrivals are Muslim.

- Version 5: Statement, plus: Of the approximately 300,000 who have fled Yemen, approximately 500 Yemenis have arrived in South Korea in 2018. Most of these arrivals are Muslim.

Next, all respondents were asked to evaluate on a five-point scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree) the statement “South Korea should accept Yemeni refugees.”

The table below combines the percentage of respondents agreeing and strongly agreeing to the prompt as well as disagreeing and strongly disagreeing. Overall, this shows the broad opposition to accepting the Yemenis. Using Version 1 (V1) as a baseline, we also see that while each other version corresponds with higher rates of opposition, those with the largest negative responses are the versions that mentioned the religion of the Yemenis.

Additional statistical analysis finds this pattern endures even after controlling for demographic factors, with our findings consistent gender, education, income, age, and political ideology. Our findings are consistent with claims that “feminists, the young, and Islamophobes have allied against desperate Yemenis.”

The results are consistent with claims of xenophobic views in Korea, although other research suggests that Korean views of nationhood are increasingly civic rather than ethnic oriented.

Nevertheless, it is clear that for many South Koreans, rhetoric will be important when discussing plans to allow in refugees, as most South Koreans remain unwilling to give Yemenis refugee status anytime soon. While the mention of the Yemenis being mostly Muslim did increase opposition by a significant margin and suggests a component of discrimination involved that has nothing to do with economic opportunity, it does not change the fact that support was low from the very beginning.

Therefore, in addition to being slow to name the majority religion of these refugees, politicians might also consider a means of working around rhetoric that portrays them as refugees, given the disproportionate connection that the word “refugee” often has to “Muslim.”

The survey used in this article was funded by the Academy of Korean Studies (AKS-2018-R05).