Recent reports of Chinese semiconductor chip manufacturers planning to produce 5-nanometre (nm) chips this year raise several uncomfortable questions for American efforts to restrict China’s capabilities in this area. Instead of delivering a fatal blow to China’s chip industry, have export controls made it more innovative?

Although 5nm chips are one generation behind the cutting-edge 3nm chips currently produced by the most advanced manufacturers, the fact that China is continuing to advance its capabilities into the sub-10nm range is significant, especially when considering that the threshold set by the United States in its 2022 export controls was 16nm to 14nm.

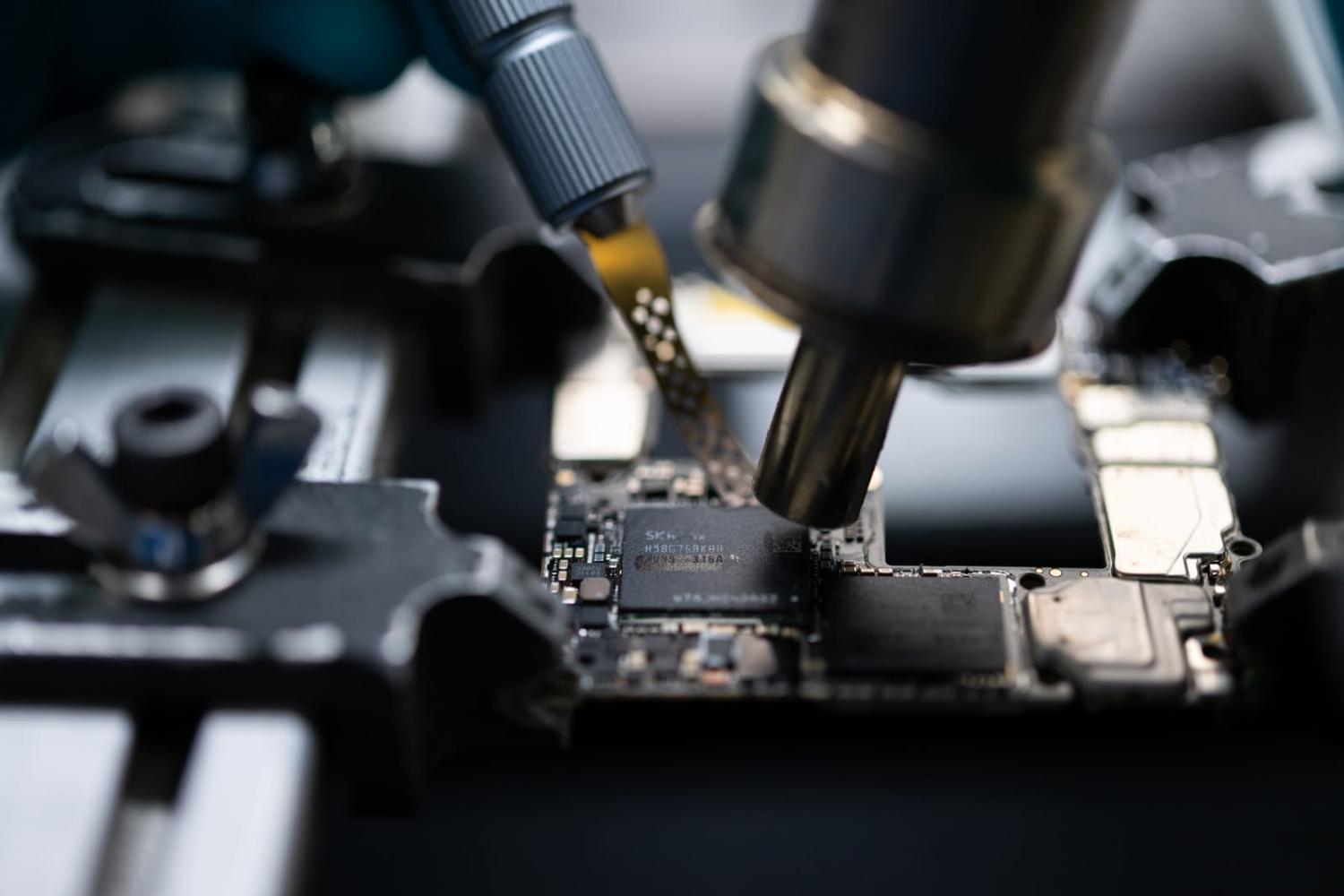

When Huawei launched its Mate 60 Pro smartphone in August 2023 containing a 7nm chip manufactured domestically by China’s top chipmaker – the Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (SMIC) – the United States was quick to claim that there was no evidence SMIC could produce 7nm chips at scale.

Some analysts were similarly sceptical that SMIC’s 7nm process was commercially viable as it does not use the latest type of chip manufacturing equipment with extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography technology that China has no access to because of export controls. There would be only so much that Chinese chipmakers could squeeze out of their older deep ultraviolet (DUV) lithography equipment using a costlier, less efficient manufacturing process.

However, monetary costs may not be as significant a barrier when political stakes are high. Even though SMIC’s sub-10nm chips cost more than they would if manufactured elsewhere using a more efficient process on EUV lithography equipment, they demonstrate China’s ability to defy US export controls.

More importantly, aside from applications related to artificial intelligence (AI), most existing military use cases are not reliant on sub-10nm chips and use older chip technologies that China already has established capabilities in. Export controls targeting the most advanced chips mainly used for AI-related applications thus restrict only a small part of the overall capabilities that the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) can currently field in a military confrontation.

This does not mean that export controls will not bite in the long term. The PLA’s ongoing modernisation effort is driven by a view that future wars will be “intelligentised” in nature and dependent on AI-driven systems. The demand for advanced chips needed for AI-related applications can therefore be expected to grow and come up against the hard limits imposed by China’s lack of EUV lithography equipment.

The reality is that China’s recent advances in producing sub-10nm chips depend entirely on foreign technology, whether it is the equipment used to manufacture chips or the software needed to design them. China’s efforts to produce its own lithography equipment have come up short, forcing domestic chipmakers to use foreign equipment.

Export controls have also been more effective for lithography equipment because there are only a few suppliers globally, and just one – the Dutch company ASML – for EUV lithography equipment. ASML’s compliance with US export controls despite nearly half of its business coming from Chinese customers is of the few bright spots in what has otherwise been a muddled exercise in economic coercion by the United States.

Where is this cat-and-mouse game between the United States and China headed? SMIC’s ability to advance from 7nm to 5nm chips should not come as a surprise given its willingness to tolerate a significantly lower yield from the manufacturing process and the resulting upward pressure on costs. However, manufacturing the next generation of 3nm chips with DUV lithography equipment at what would likely be an even lower yield could be impractical, even if SMIC appears committed to pushing the limits of what can be achieved.

What is clear is that China will continue to back its domestic chip industry generously, despite recent frustrations over corruption. In September 2023, a third iteration of the China Integrated Circuit Industry Investment Fund – also known as the “Big Fund” – was announced with a target of 300 billion yuan. This is significantly more than the previous two iterations of the Big Fund, which raised 138.7 billion yuan and 200 billion yuan in 2014 and 2019 respectively.

But the long-term innovative potential of China’s chip industry is not solely dependent on how well funded it is. Neither is it a function of how many patents it files. Zealous intervention in the chip industry to direct and support its progress, despite yielding some results in the short term, may ultimately prove to be its biggest stumbling block, as innovation is seldom manufactured or bought.

This does not mean that the United States can rest easy thinking that the main impediment to China’s chip industry advancing is the very nature of its own political system. Continuous calibration of export controls will be needed, as well as consideration of new approaches, such as designing chips in a way that allows export controls to be enforceable at the hardware level.