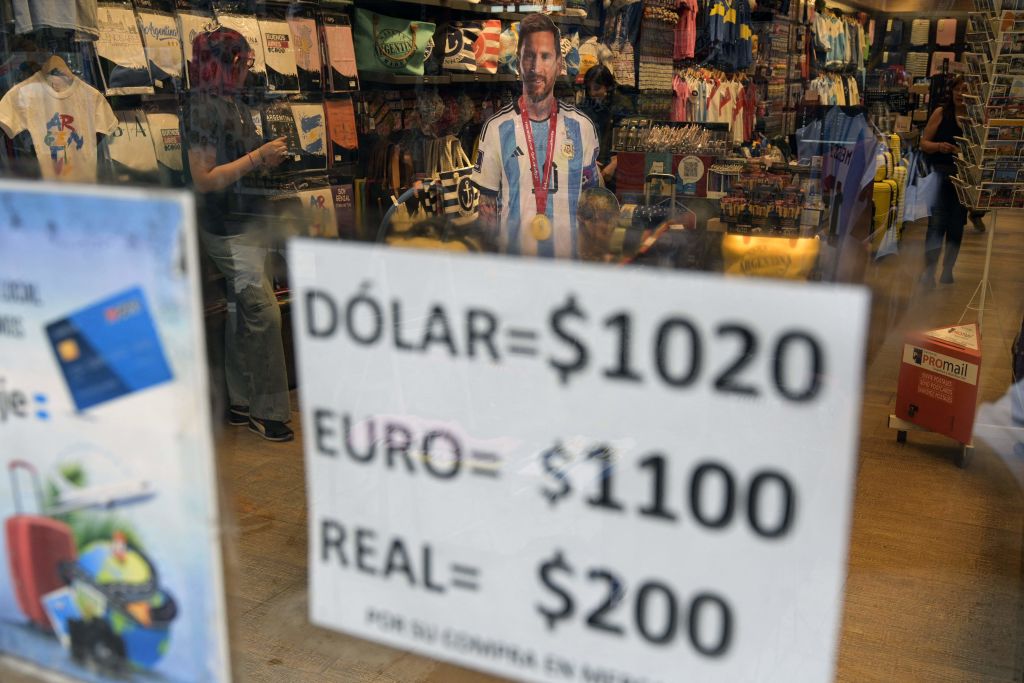

Argentina’s international position combines weakness, defective policies, and until now loud but empty claims mostly driven by ideology – whether proffering a view on Venezuelan politics or how to deal with Iran. After several decades of decay, Argentina’s own economic capacity and military capabilities are in disarray. The country has plenty of resources for primary production, which are in high demand in the world: food, minerals, and energy. But they can’t be transformed into state capacity for political reasons, as corruption dominates the political stage, and public spending has created substantial economic turbulence.

So the only consistent foreign policy from Argentina during the past year and more was asking for the world for money. A foreign analyst could compare the country with a beggar.

But change is promised. In the last round of elections, an uncertain project prevailed, an economically liberal and politically conservative pledge to “Make Argentina Great Again”. Javier Milei, the president elect, has stolen the international headlines, but this was a coalition built among two smart and different politicians: a liberal globalist and a nationalist catholic leader.

Unfairly branded as an alt-right/extreme-right movement, the truth is that Milei won the election thanks to an informal alliance with his former competitor, Patricia Bullrich, from Juntos por el Cambio, a moderate centre-right coalition, showing a pragmatic way to do politics. They proved more sensitive to society’s requirements than the defeated government of Frente de todos por Union por la Patria. Milei ran his campaign with a message of transforming anger over economic collapse and structural corruption into hope.

Milei has his well-canvassed beliefs, but now he will be the head of state, he has said he must act as such. He knows that politics is about constraints, opportunities, and making sustainable alliances to achieve goals. He has good communication skills with his base and those who voted for him. People in Argentina took a stance in this election. Milei won with 56 per cent of the votes in the run-off ballot. The informal vote was lower than expected. People voted to have a functional economy with fewer restrictions.

Milei has named economist and professor Diana Mondino as foreign minister and provided some clues about their first movements in the international arena once his administration is inaugurated on 10 December.

The first challenge will be to overthrow myths about erratic behaviour, fascism, and accusations about climate change denialism. Thanks to a long campaign full of misinformation and shrill declarations made out-of-context, his administration will face a credibility test immediately. Questions about Argentina’s relations with China and Brazil are frequent, and G20 leaders wonder if he is a “leap into the void” as opponents have said about him.

His administration must also present a coherent grand strategy aligning the 21st century international context with Argentina’s development requirements. This is, of course, in addition the task of acquiring the financial means to pay its debt. Milei’s foreign policy will be judged by its capacity to reduce the poverty rate, which is 40 per cent in the country, its capability to improve its economic structures, and the results of its intended economic openness.

Milei wants to do business with every country in the world, however, in issues related to international security, he looks for a closer relationship with the West. He presented his ideas and values during the campaign in plain language that was easy to understand: ambiguity is not an option for a vulnerable country like Argentina. Hedging, or a variant known as equidistance politics, is not advisable, and the administration does not want it. But cognisant of the intricacies of international politics, Milei’s foreign policy will move between alignment and selective engagement.

The new administration will strive for transparency in diplomacy. Milei wants every agreement made to be as open as possible to the Congress and Argentine civil society. All the accords that President Alberto Fernández and Vice-President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner made had secret clauses. Examples include the Chinese space station in Neuquén, the interest rate of the swaps lent by China to Argentina, or the agreement made with Chevron a decade ago when Fernandez de Kirchner was president. In a country where political corruption has an external dimension, transparency could improve Argentina’s global standing.

On issues such as climate change, the agenda remains unclear. But as the trade agenda relates to the issues discussed in climate negotiations, adaptation will probably be the path followed.

And there will be a narrow definition of the administration’s objectives in defence. The necessity for a modern military will depend on Argentina’s ability to obtain military capabilities from the United States and its partners, and to terminate the anachronic and harmful veto over military equipment from the United Kingdom, which drove chauvinistic audiences in Argentina to form a kind of alliance with China.

Milei’s foreign and domestic conservative policies came at the right moment as an attempt to stop Argentina’s long decline.