Indonesian Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi highlighted the importance of developing what she called “strategic trust” in Australia-Indonesia relations, just ahead of the visit to Canberra this week by President Joko Widodo (“Jokowi”). Retno declared a more trusting Australia-Indonesia relationship would be a “significant advantage” for the Indo-Pacific region.

It’s a view echoed by close observers of the relationship, and it is certainly true. The relationship has stereotypically been described as a roller coaster – beset by crises, sometimes large and sometimes small, one that has struggled to maintain an even momentum. Or to put it another way, as does analyst Yohanes Sulaiman, the relationship rests on “very slender reeds”.

But how do Australia and Indonesia build trust, and what are the prospects for doing so?

Cooperation on shared interests will provide opportunities for interaction – and hopefully not only between government ministers and diplomats, but also business people, students and educators, tourists, and others.

Much has been and will be made of Jokowi’s visit to Australia. The first Indonesian president to address parliament since former president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono’s visit in 2010 certainly marks a significant occasion. The relationship has often done well when relations between leaders have been strongest. This is unsurprising, given the limited interactions and relations available elsewhere in the relationship. More than good leadership relations is required, however – even more so for those times when leaders fall out.

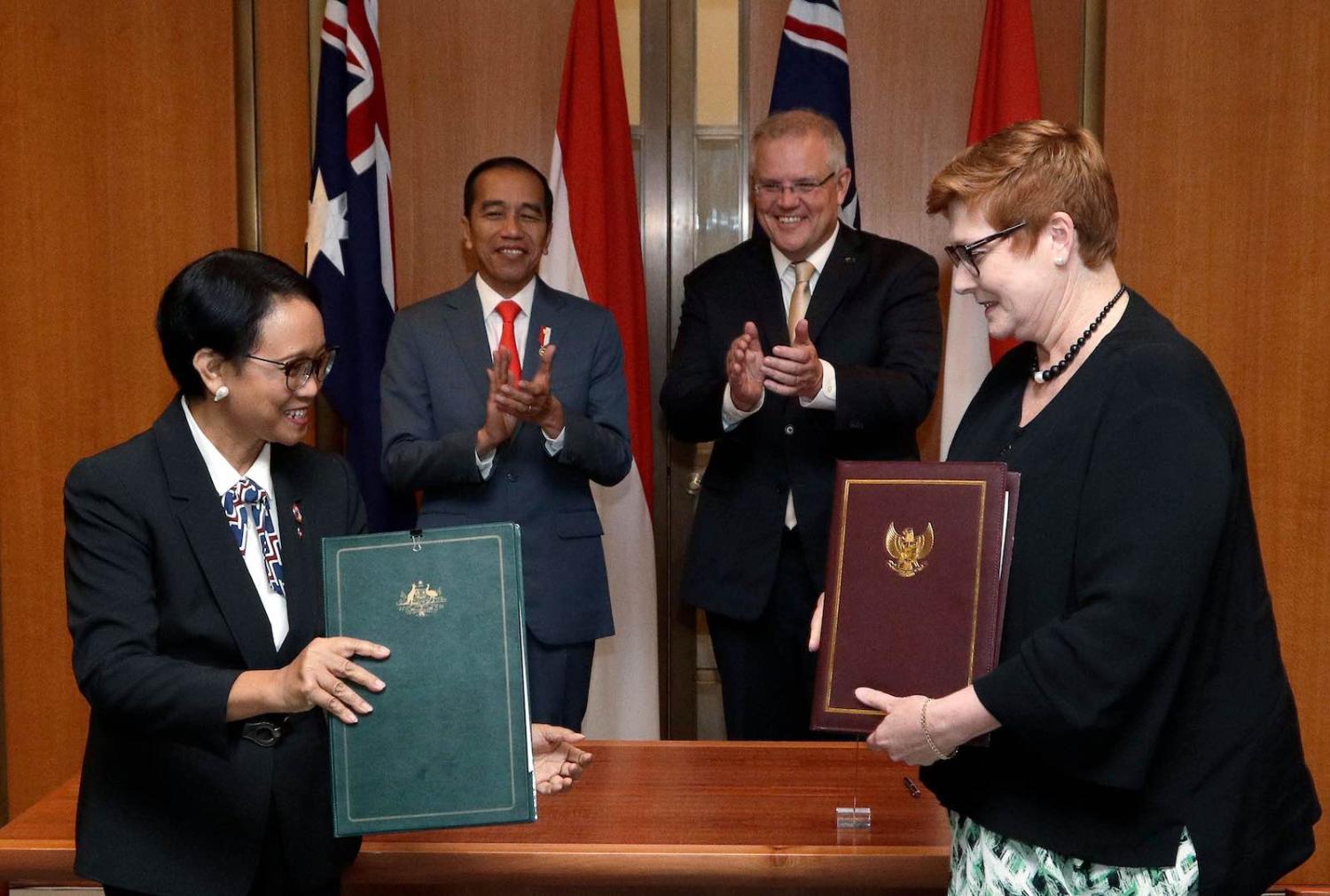

Shared economic interests are at the heart of Jokowi’s current visit, with attention focused on the signing of the Indonesia-Australia Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (IA-CEPA) and its implications. A focus on shared interests can be misconstrued as merely transactional. But shared interests can provide an important foundation for the development of trust. Indeed, when it comes to relationships between countries, interests can never truly be divorced from trust.

A transactional, overtly “me-first” approach will cause harm to a bilateral relationship, as will acting in a way which breaches established norms or expectations. A mutual, respectful negotiation of shared interests, however, will aid in the development of shared expectations of trustworthiness. The better the understanding each country has of what the other expects from them, the less likely expectations will be dashed, and trust violated. This is what happened, for example, when Prime Minister Scott Morrison announced a review of the location of the Australian embassy in Israel.

Given their proximity, Australia and Indonesia will always have opportunities to negotiate and cooperate on shared interests. As Retno puts it, “There is no option for both Indonesia and Australia other than identifying areas of mutual interest and seeking closer relations.” The difficulty is ensuring shared expectations of trustworthiness are in place regarding how to cooperate on shared interests, how to manage disagreements, and also resisting the temptation to allow short-term interests elsewhere to be given a higher priority than the relationship.

Trust also requires, above all else, opportunities for interaction. Cooperation on shared interests will provide opportunities for interaction – and hopefully not only between government ministers and diplomats, but also business people, students and educators, tourists, and others. The IA-CEPA will provide more opportunities for cooperation between both governments and the private sector than a free trade agreement. One example of this is the agreement to a reciprocal skills exchange, which will allow for people from both countries to undertake six months of experience in the other country if they have tertiary-level skill qualifications. Another is the announcement Monash University will be opening a campus in Indonesia, the first foreign university to do so.

While all of this holds the promise of potential, trust between Australia and Indonesia presently remains quite limited, and there is lots of work that needs to be done in order to improve matters, particularly given the challenges that face the two countries. From managing human rights disputes to China’s presence in the South China Sea, to climate change – there are many opportunities for disagreement and crisis, and many opportunities for cooperation.

Despite the challenges, there is hope that this time the mutual interest both countries have shown in developing trust with one another will mean that the resilience the relationship has shown in repeatedly bouncing back from crises can be put to better use: preventing crises in the relationship from happening in the first place, and managing regional and global challenges together.