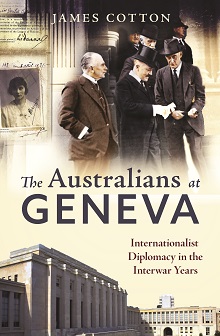

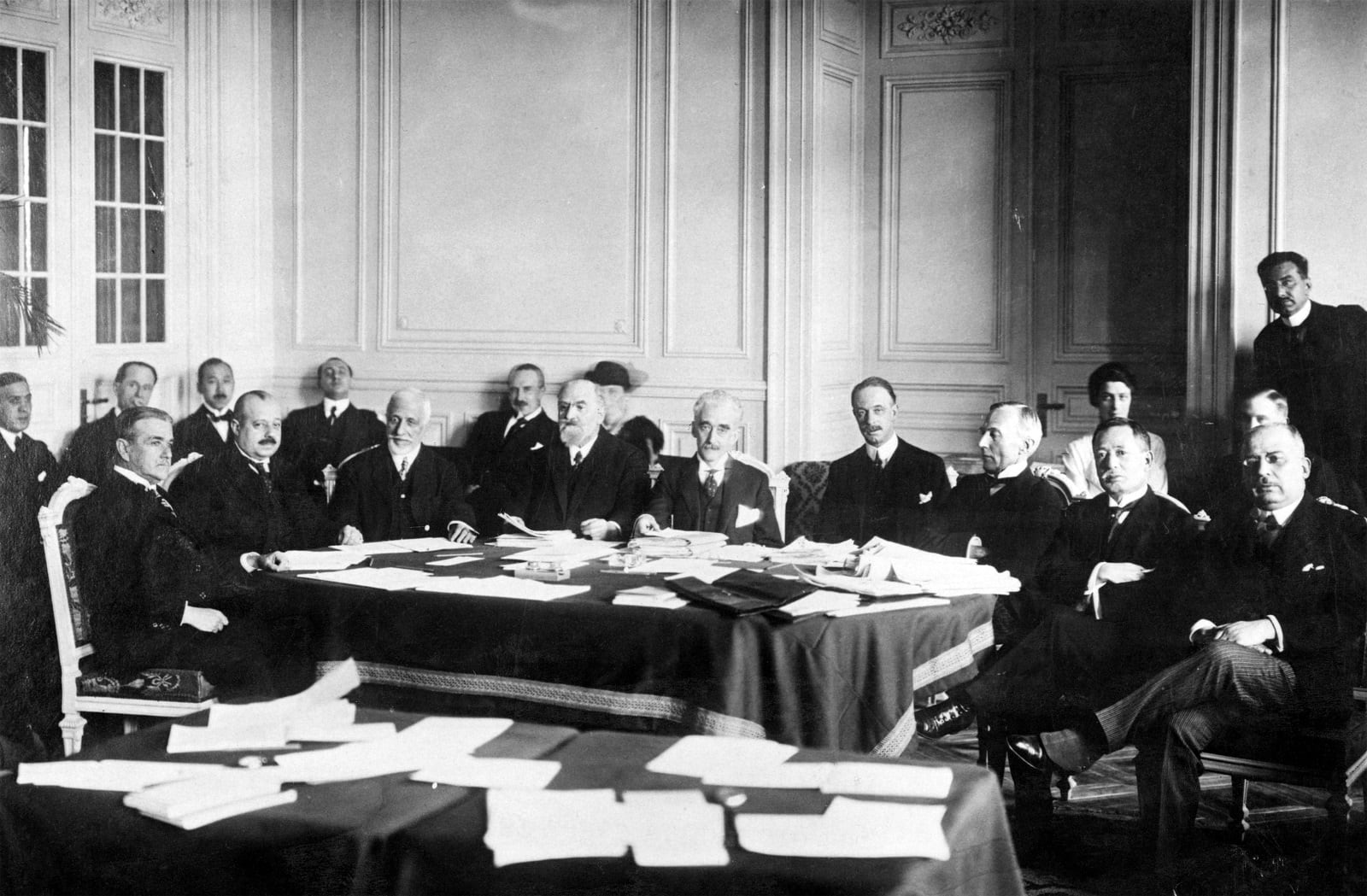

From the 1920s, Geneva, as the home of the League of Nations, became the principal focus of international diplomacy. Although Australia’s role as an international actor was in its infancy in the interwar period, Australians played a direct though unacknowledged part in the construction and defence of international norms that was a central focus of the era. The Australians at Geneva in the interwar years, as detailed in my new book examining this history, helped make credible the idea of ameliorative global governance. A surprising number of them visited, sojourned, or lived in the League city, generally lending their talents and enthusiasm to its internationalist project. They included not merely the official delegates, but the more humble (and often more earnest) invitees, the talented functionaries working in its administrative machinery, and the multi-lingual secretaries and assistants who were essential for its operations. It was a precursor to many of the same type of themes and challenges the world continues to grapple with.

From the 1920s, Geneva, as the home of the League of Nations, became the principal focus of international diplomacy. Although Australia’s role as an international actor was in its infancy in the interwar period, Australians played a direct though unacknowledged part in the construction and defence of international norms that was a central focus of the era. The Australians at Geneva in the interwar years, as detailed in my new book examining this history, helped make credible the idea of ameliorative global governance. A surprising number of them visited, sojourned, or lived in the League city, generally lending their talents and enthusiasm to its internationalist project. They included not merely the official delegates, but the more humble (and often more earnest) invitees, the talented functionaries working in its administrative machinery, and the multi-lingual secretaries and assistants who were essential for its operations. It was a precursor to many of the same type of themes and challenges the world continues to grapple with.

Initially, Australia’s official engagement with the League was in pursuit of a limited agenda, notably maintaining tariff autonomy, the White Australia policy, and unfettered control of the League of Nations’ mandated territory of New Guinea. However, as the League’s ambitions and potential grew, addressing issues from disease control and financial dislocation to the codification of international law, some Australian delegates returned from the annual Assembly meetings of member states with considerable enthusiasm for the potential of progressive internationalism. By the 1930s, former prime minister Stanley Bruce, effectively by then Australia’s chief delegate to Geneva, embraced the goal of improved global nutrition as a preventive of a key source of international conflict (as well as being beneficial to Australian primary exports).

Australians also made their careers at Geneva, becoming public servants of internationalism. William Caldwell, Raymond Kershaw and H. Duncan Hall were all members of the Geneva institutions.

The neglected career of William Caldwell at the International Labour Organisation is a good example. Despite serving with the agency from 1921, visiting Australia regularly, influencing Prime Minister John Curtin and Attorney-General H. V. Evatt, and raising such issues as Aboriginal labour, the few Australian studies of the early ILO have not given Caldwell his due. The ILO project to develop and extend improved working standards for labour, in which Caldwell was an early and enthusiastic participant, continues to the present.

Raymond Kershaw worked in the Secretariat of the League in the highly sensitive area of minorities’ protections. While the rights of minorities were recognised by treaties guaranteed by the League, once Germany joined the organisation these treaties came to be seen as potentially infringing its role as an aspirant major power. Although Kershaw was highly regarded by his section of the League Secretariat, his contribution has hardly been acknowledged by Australians. His later career at the Bank of England and as bag carrier for the Bank’s Sir Otto Niemeyer on his Australian mission in 1930 cannot be properly understood without acknowledging his League experience.

In the League Secretariat 1928–37, H. Duncan Hall undertook path-breaking work on narcotics control. He effectively designed an international drug regime – the functioning of which depended upon national transparency and cooperation on manufacture, use and export – in order to constrain the illicit international trade. This system was sufficiently effective to include some League non-members, notably the United States. Even in the early 1930s, these measures were seen as suggesting a possible model for arms control. In work on such international regimes, Hall is not recognised as an important pioneer.

All of these individuals toured Australia on multiple occasions, addressing meetings in the capital cities on the work of the League and the ILO and making the case for the improvement of global security and prosperity though the construction of international norms.

National delegations from Australia to the League Assembly from 1922 always included a woman representative. In 1931 and 1932, Dr Ethel Osborne raised such issues as gender equality in the laws relating to citizenship as well as child welfare and protection. She was an impressive performer, being asked to address the Assembly in plenary session. Perhaps the most influential woman delegate was Bessie Rischbieth, founder of the Australian Federation of Women Voters. At the 1935 meeting, she spoke on women’s rights of nationality, nutrition, child welfare and gender equality. In 1936, as the League’s international security role faced the severe test posed by the Italian invasion of Ethiopia (then also a fellow member state), she argued the case for the international rule of law as the only alternative to what would otherwise become “the survival of the fittest”. What was at fault, she maintained, was not the League but the policies of its member states. Nevertheless, its prospects would be improved by measures to feminise international relations. On their return from Geneva, both these women popularised the League’s work in extensive newspaper articles and energetic speaking tours.

Among the unofficial ILO delegates, a number of the employees found compelling an internationalist approach to the amelioration of wages and working standards; some went so far as to embrace the anti-colonial critique of the harsh working conditions to be found in the Asian economies.

The cast of Australians at Geneva included ancillary staff and contributors to the League’s outreach. Among the original employees were Australian clerical workers, mostly women. Despite the fact that one, Adelaide-born Jocelyn Horn, seems to have been dismissed for indulging in excessive dancing, the late Frank Moorhouse (author of the Edith Campbell Berry trilogy set in Geneva) seems not to have known they existed, since his chief character was based on a Canadian original.