Overnight, a Nobel laureate and former professor of literature died from complications of liver cancer. He had been imprisoned for more than eight years and appears not to have received genuine medical attention at a municipal hospital until recent weeks, when his illness was well advanced. On his deathbed, police guarded his room and barred all visitors except for immediate family members. Two foreign doctors were allowed to see him but authorities denied his request to leave the country for medical care.

What had this man done to deserve such degrading treatment? And why did a powerful nation like China prevent him from living out his remaining days in dignity and freedom?

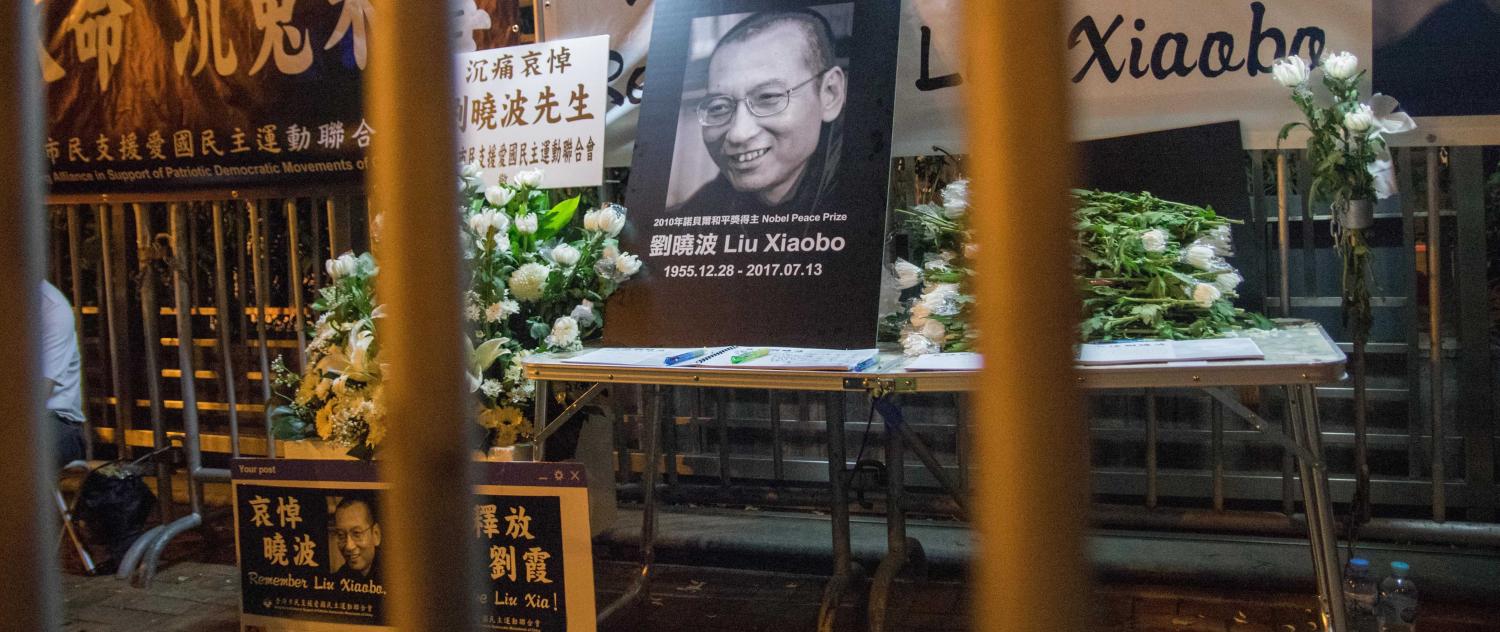

Liu Xiaobo was a brilliant academic who wrote on Chinese society and culture with a strong focus on democracy and human rights. In other countries, his works would have been published, his ideas debated, and his intellectual contribution to society celebrated. But in China, for his efforts Liu only saw the inside of a prison cell.

After the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre, Chinese authorities jailed Liu for 21 months for his role in supporting students who had taken part in the peaceful protests.

For a brief period in 1993, Liu lived in Canberra. He was reportedly offered asylum by Australian authorities, but turned down the offer. After returning to China, authorities imprisoned Liu again for three years in 1996 for his human rights activities.

In December 2008 Liu was detained for his role in co-authoring a pro-democracy manifesto called Charter 08. A year later, he was convicted of ‘incitement of subversion of state power’ and sentenced to 11 years in prison. He was incarcerated ever since.

In 2010, the Norwegian Nobel Committee awarded Liu the Peace Prize. China did not allow him to attend the awards ceremony in Oslo. Instead, a chair stood empty on the stage as a reminder of China’s unrelenting and cruel repression. Angry at the world’s celebration of Liu, Chinese authorities meted out retribution on his wife, Liu Xia, who has been held under house arrest without charge ever since the award ceremony.

After Liu won the Nobel Peace Prize, countries around the world urged China to free him. Australia’s then-Foreign Minister Kevin Rudd raised Liu’s case with the Chinese authorities. Julie Bishop, then in opposition, wrote an op-ed about Liu urging China to let him attend the ceremony.

But as Liu lay dying in the hospital, there was a shameful silence from Australia’s leaders on Liu’s case. Canada, France, Germany, Taiwan, and the US all called on the Chinese authorities to free Liu and allow him and his wife to travel abroad for medical treatment. Australia made so no such call.

Perhaps Australian officials thought raising his case publicly would be ineffectual. Perhaps they thought the case would not be worth risking China’s ire. But they should be reminded of what Liu told a journalist back in 2007:

Western countries are asking the Chinese government to fulfill its promises to improve the human-rights situation, but if there’s no voice from inside the country, then the government will say, ‘It’s only a request from abroad; the domestic population doesn’t demand it.’ I want to show that it’s not only the hope of the international community, but also the hope of the Chinese people to improve their human rights situation.

As the Chinese government commits abuses at home without accountability, ratchets up repression in Tibet, Xinjiang and Hong Kong, and abducts people beyond its borders, precisely the kind of pressure Liu called for is needed from both inside and out. China’s human rights defenders like Liu are the ones that risk their lives, yet without international support they are even more vulnerable.

Liu was one of thousands of political prisoners in China who have lost their freedom to boldly call for the rule of law, respect for basic rights, and democracy in China. Australia should not let his death pass without challenging Beijing on his mistreatment. Australia’s leaders should also call upon China’s leaders to allow Liu Xia to leave the country if she chooses and mourn her husband as she sees fit.

Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull likes to speak of freedom. This week in London he said, ‘to defend freedom we cannot give free rein to its enemies’. It’s time to stop having those discussions in the abstract and speak up on behalf of courageous people in China such as Liu Xiaobo, especially when they most need it.