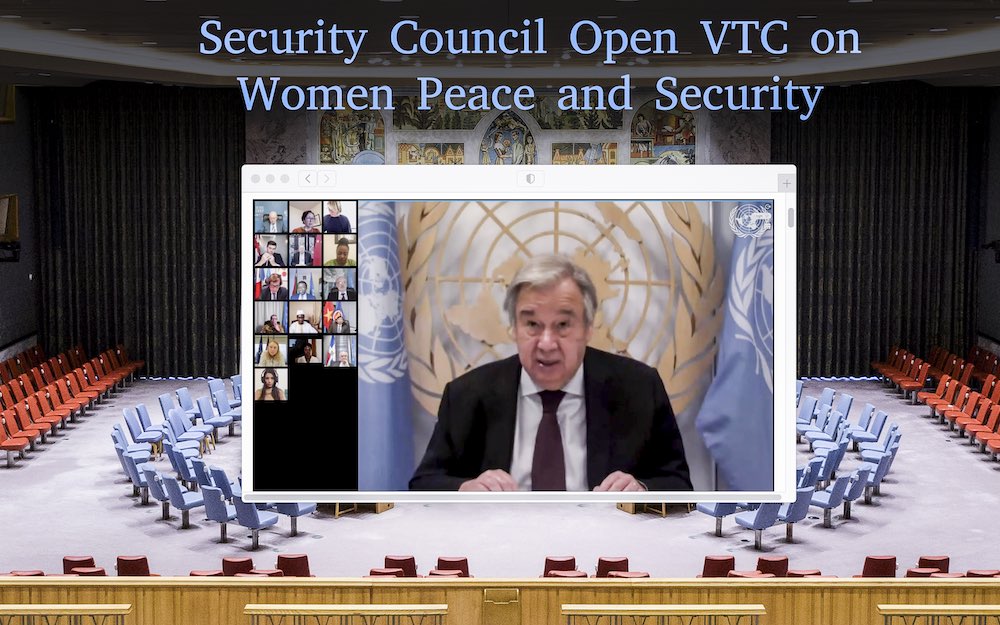

Twenty years ago, the United Nations Security Council passed Resolution 1325, a landmark to formally recognised the disproportionate impact of conflict on women and girls. Yet this year, there is no new resolution to mark the anniversary of what became the Women, Peace and Security (WPS) agenda, only contentious politics. At the annual open debate of the UN Security Council on 29 October, five countries, including Indonesia, Vietnam, China and South Africa voted for a Russian-initiated draft resolution. Yet ten countries abstained. In his speech at the debate, UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres stated that “gender equality is first and foremost a question of power, and wherever we look, power structures are dominated by men.”

If it had not been clear before, the full and meaningful implementation of the WPS agenda is also a question of power – the power politics among states. But the contentious politics around WPS is unprecedented this century, and recalls the UN World Conferences on Women during the Cold War.

Russia’s presidency of the Security Council

The Russian Permanent Representative to the UN, Vassily Nebenzia, assumed the Presidency of the Security Council for the month of October 2020. To commemorate the 20th anniversary of UNSCR 1325, Russia initiated the negotiation of a new draft resolution (S/2020/1054). Ambassador Nebenzia’s letter to the UN Secretary-General encouraged “provisions that relate to the specific needs of women and girls” in conflict and post-conflict. It emphasised the importance of meaningful, vocal women’s participation in peacebuilding efforts.

Russia has challenged the broad consensus on the WPS agenda and positioned itself as a power supporting the traditional role of women.

The debate took place on practically the last day of the Russian Presidency, and one year after the representative of the Russian Federation at the General Assembly stated that Russia is fully committed to the improvement of the status of women. Indicating Russia’s apparent attention to the call for gender parity at the UN, Anna Evstigneeva was appointed in October as the first female Deputy Permanent Representative at the Russian Mission.

However, Russia has demonstrated resistance to WPS in both words and actions across the two decades since the adoption of the UNSCR 1325. In 2000, Sergey Lavrov, Russia’s then-ambassador to the UN, noted that “‘women’, ‘peace’ and ‘security’ combine harmoniously, because this harmony is predetermined by nature.”

Twenty years later, Nebenzia linked women’s rights to the family, concluding the 29 October debate with the statement “the family is of special value, we must ensure its protection”.

Indonesia’s non-permanent Security Council membership

While Indonesia voted for Russia’s proposed resolution, it contrasted sharply with Indonesia’s full commitment to implementing the WPS agenda during its two presidencies of the Security Council as a non-permanent member (in May 2019 and August 2020). Indonesia’s support for WPS was evident through its leadership of the successful adoption of UNSCR 2538, which recognised women as the agents of peace and called for greater gender equality in participation in peacekeeping missions.

By contrast, Russia’s proposal suggested an attempt to downgrade UN commitment towards women’s roles and rights in peace and security efforts. Moreover, Indonesia’s earlier draft resolution on prosecution, rehabilitation and reintegration (PRR) strategies at the end of its August presidency evidenced its recognition of the importance of women’s full participation in addressing the root causes of terrorism. While this proposed resolution was ultimately vetoed by the US, it revealed Indonesia’s concerted effort to enhance women’s inclusion within all PRR strategies and as part of the efforts to promote international cooperation to prevent violent extremism.

Indonesian leadership on Women, Peace and Security

Although Russia’s October presidency of the Security Council has challenged the progress achieved in promoting women’s rights and participation as matters of international peace and security, the commitment of Indonesia is intact. Indonesia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs has integrated the WPS agenda within the country’s commitment to “investing in peace” and building the leadership capacity for inclusive peace and security. At last week’s debate, Indonesia underscored the importance of increasing women’s participation in mediation and negotiations, strengthening the capacity of female peacekeepers and encouraging a multi-stakeholder approach. ASEAN’s regional contribution within the framework of WPS also coheres with and reinforces Indonesian commitments.

From the perspective of national interest, Indonesia’s support for greater implementation of the global WPS agenda resonated with the country’s launch of its second WPS National Action Plan, which has been co-designed by the government and more than 200 civil society organisations across 25 provinces in an extensive national digital consultation process managed despite the Covid-19 pandemic. In this respect, Indonesia has strengthened its position as a key player among the middle powers furthering the WPS agenda, and reflecting the interests of the Global South.

What’s next for Women, Peace and Security?

As the power dynamics of the global multilateral order are shifting, Russia has challenged the broad consensus on the WPS agenda and positioned itself as a power supporting the traditional role of women. Russia’s “way” of commemorating the 20th anniversary of UNSCR 1325 threatens to undermine even the limited progress on mainstreaming gender in peace and security since 2000. Power politics among the Permanent Five members of the Security Council is increasingly a major impediment to a transformative WPS agenda. On a regional level, these power politics run counter to concerted efforts to elevate women’s participation in order to enhance regional security in the Indo-Pacific.

Notwithstanding the notable achievements of the WPS agenda, “progress is too slow, too narrow, and too easy to reverse”, as Guterres put it. To move the agenda forward, UN member states should support and reinforce multilateralism “from below” through partnership and sustained dialogue with civil societies to overcome the significant gendered gaps that affect security for all.