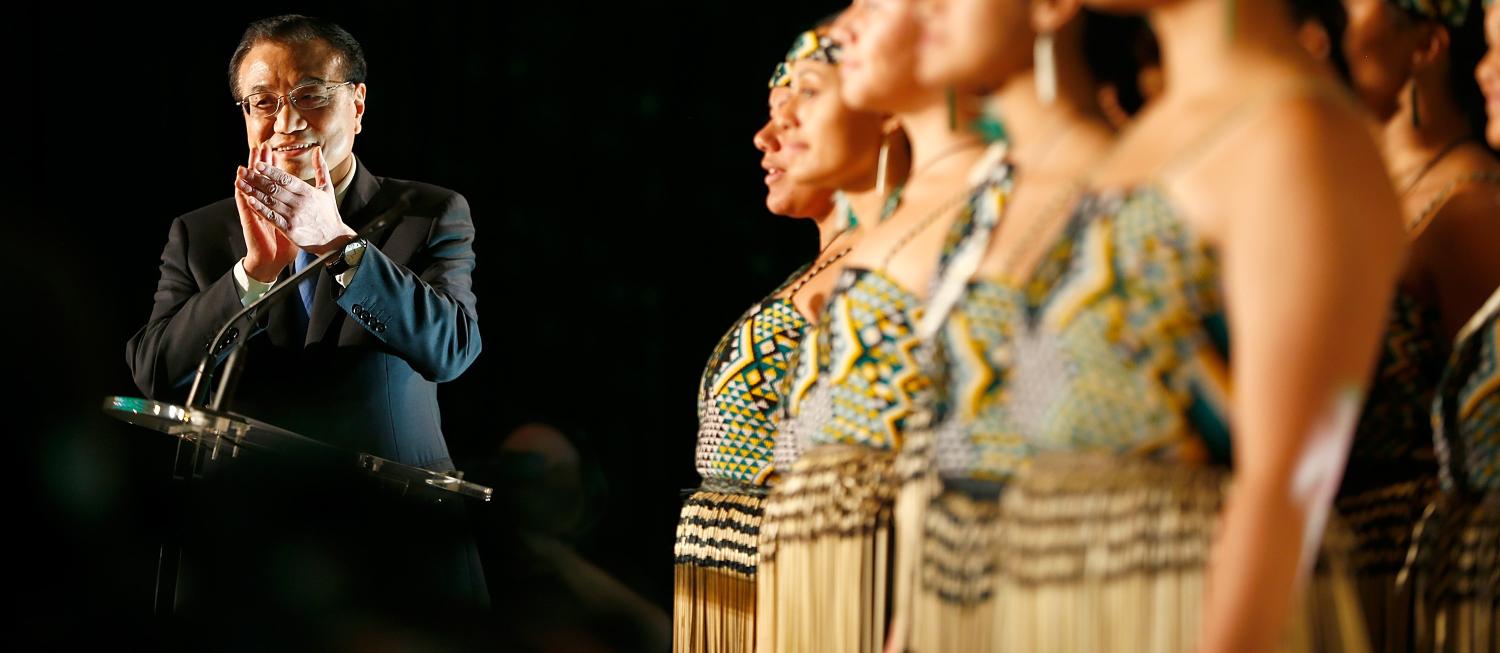

New Zealand became ‘the first Western developed country’ to join China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) when it signed a Memorandum of Arrangement (MoA) during Premier Li’s March visit. For New Zealand, signing up to the BRI was the logical next step in a long-held policy of engagement with China and one that marks the very early stages of New Zealand’s BRI negotiations.

BRI is a loosely defined development strategy that organises China’s existing relations with the developing world and seeks formal state-to-state partnerships to promote development and connectivity in the region. It is a state-led but commercially delivered model of development that focuses on improving both the ‘hardware’ (transport infrastructure) of the regional economy and the ‘software’ that regulates the movement of goods, capital and people.

Taken at face value, BRI aligns closely with New Zealand’s compulsive membership of regional economic integration initiatives. BRI is, however, unlike previous regional economic integration initiatives that directly or indirectly linked economic connectivity with good governance and democracy promotion. BRI is China-led, has no stated position on political or security issues and draws from a different historical imperative.

BRI is a stripped down version of development economics that draws on China’s own development experience. Over the last 40 years Chinese policymakers have embraced economic liberalisation and industrial policy while decreasing restrictions on engagement with the global economy, all the while maintaining, if not strengthening, one-party rule. BRI is the international expression of this domestic experience. It embraces development and economic integration but neglects those elements of the liberal order that do not fit easily with China’s own experience and system of government.

New Zealand’s decision to join BRI follows the logic of decades of New Zealand engagement with China. New Zealand made an early bilateral agreement on terms for China’s WTO accession and achieved a comprehensive free trade agreement far earlier than other advanced economies. New Zealand signaled an interest in early membership of the AIIB and has established cooperation programs with China for military exchanges and trilateral development projects in the Pacific. Such engagement follows the logic that where New Zealand interests are concerned, it is better to proactively work with China than to respond passively to Chinese activities.

Following this logic, New Zealand’s openness to BRI signals a political willingness to seek innovative engagements that can go some way to ameliorating the economic asymmetry of New Zealand-China relations and to seek a new forum to present our bilateral and regional interests. It also signals a high-level acknowledgement of China’s strategic rise in the Asia Pacific.

Australia, given the same opportunity, chose to err on the side of caution, to wait to learn more about the initiative and to ponder whether or not it represents a ‘profound challenge to the current global political and economic status quo’. While New Zealand authorities decided to be at the table, to try to shape the Initiative in areas where it touches on New Zealand interests, such as the Pacific, Australian authorities appear instead to want more analysis, to observe how activities under BRI are rolled out and to figure out just what China’s regional strategy could mean for Australia and the region.

As an expression of Chinese grand strategy, however, it will be very hard to fully ascertain just what BRI is even as the number of activities under the BRI framework grows. That is because Chinese grand strategy, whilst highly aspirational, has flexibility deliberately built in.

For all participating countries, but especially for advanced economies, there is a ‘blank page’ clause in the BRI or a reassurance that China will work together with them to develop activities in consideration of each countries’ interests. BRI activities therefore flow from the bilateral negotiations following the initial signing of the MoA and require participating countries to present their own vision of how BRI should evolve. For many this uncertainty is unsettling because it is impossible to figure out exactly what one is committing to in the initial MOA. But this flexibility also provides an opportunity for countries like Australia and New Zealand to shape China’s activities in our region.

The MoA New Zealand signed is the beginning of a negotiation for developing ‘a more detailed work plan of bilateral cooperation’ over the next 18 months. This negotiation is especially important because New Zealand is the first advanced economy to engage in this process, thus setting precedents that will in some small way determine the final form of the overall BRI.

As the world’s second-largest economy turns its attention to economic integration and the provision of regional public goods, countries like Australia and New Zealand have a period of strategic opportunity to shape these activities. It is therefore reasonable for them to accept the overarching BRI concept in exchange for a seat at the table to ensure their interests are heard.