I have known two “professors of everything”: George Seddon and Robert May. Seddon, who ended his days in Fremantle, Western Australia, had chairs in geology, English, environment, and philosophy. The connection, he told me, was language. May’s fields were chemical engineering, physics, maths, ecology, zoology, and then finance. He died last week in Oxford.

Neither men were dilettantes. What they represented, and their brilliant careers show, is the ubiquity of science: it is the basis of modern civilisation, its wealth, knowledge, security, health, and future. Linking the subjects for May, in my opinion, was maths, though he disputed this. He said that he was instead excited by problems that seem to have ready solutions and that his flexible mind could leap at and tackle – until the next one arrived.

While at school, May joined the debating team and later said this was the experience that prepared him magnificently for dealing with audiences and prime ministers.

May’s family was Irish and Scottish and left Ireland when threats from the IRA became too worrying. They arrived in Newcastle, NSW, and lived roughly, with a dirt floor and few prospects, until May’s father proved to be a brilliant lawyer and set them up in comfort. May went, crucially, to Sydney Boys’ High School and was galvanised by an inspiring chemistry teacher, Lenny Basser, who refused to let the boys grind through the syllabus but instead told them which were the hot topics, where the good books were, and had pupils write essays exploring the crucial ideas.

While at school, May joined the debating team and later said this was the experience that prepared him magnificently for dealing with audiences and prime ministers. By then his father had left the family, a catastrophic drunk. May became a lifelong teetotaller as a result.

The University of Sydney, like school, was a joy for the young man, who became expert at passing exams and combining seemingly impossible loads of subjects. But it was physics and the flamboyant presence of Professor Harry Messel that inspired May to try greater challenges – supported by the dream team of scholars Messel had assembled.

Bob May is dead. Lord May OM, PRS. Chief Scientific Advisor to Government, 1995-2000. Crafoord Prize. Hugely distinguished theoretical ecologist & epidemiologist, pioneer Chaos Theory & much else. He was publicly generous about and to me, despite my being no mathematician. R.I.P.

— Richard Dawkins (@RichardDawkins) April 28, 2020

I met Bob, as he preferred to be called (even when elevated to a lordship), in the late 1970s. My friends told me he was the smartest boffin in Australia, if not the world, and we clicked from the start. He was direct, very well informed, and keen to make a difference. After a spell in Australia, he was preparing to head off to Princeton in the United States and eventually run the University’s entire research effort. He was encouraged to find it not too large, requiring only one or two days a week in meetings, leaving the rest of the time for his own projects.

This preparation, combining real leadership with hands-on research, was perfect for a call that came when he’d returned the UK, to Oxford as a professor, this time, of zoology: Britain needed a Chief Scientist. We nearly had a fit – a combination of hilarity and bewilderment – when May took the job. He never minced words. Would the pommy protocols and sensitivities give him just a short, sharp tenure? But the opposite turned out to be the case.

May’s experience of ecology at Sydney and Oxford, putting numbers to biodiversity and environmental change, proved invaluable when Mad Cow Disease overwhelmed Britain and HIV spread across the world. His mapping of the outbreaks for the government was matched by a vital sense of urgency. And, as climate change became to him and the Royal Society a pressing challenge, he was characteristically outspoken and blunt.

In fact, a story is told (by Lord William Waldegrave, then a minister) that Bob May was the first person in history to use the phrase “that’s bullshit” in the Cabinet room at 10 Downing Street. I was told a more powerful word, beginning with F, was also a historic breakthrough of May’s. His Australian background was a safe alibi. His integrity even more so.

In the year 2000 May moved naturally from his superb handling of the position of Chief Scientific Adviser to PMs John Major and Tony Blair to the Presidency of the Royal Society, a successor to Banks, Newton, and Florey.

His standoff with the climate “sceptics” continued, not least in the House of Lords, where he now was a member. (He did, incidentally, want to be Lord of a Sydney suburb, Woollahra, but received a rare refusal and settled instead for “of Oxford”. Then he was utterly chuffed when offered the ultimate gong: the Order of Merit (OM), an award which is in the personal gift of The Queen and which is limited to 24 members at any one time.

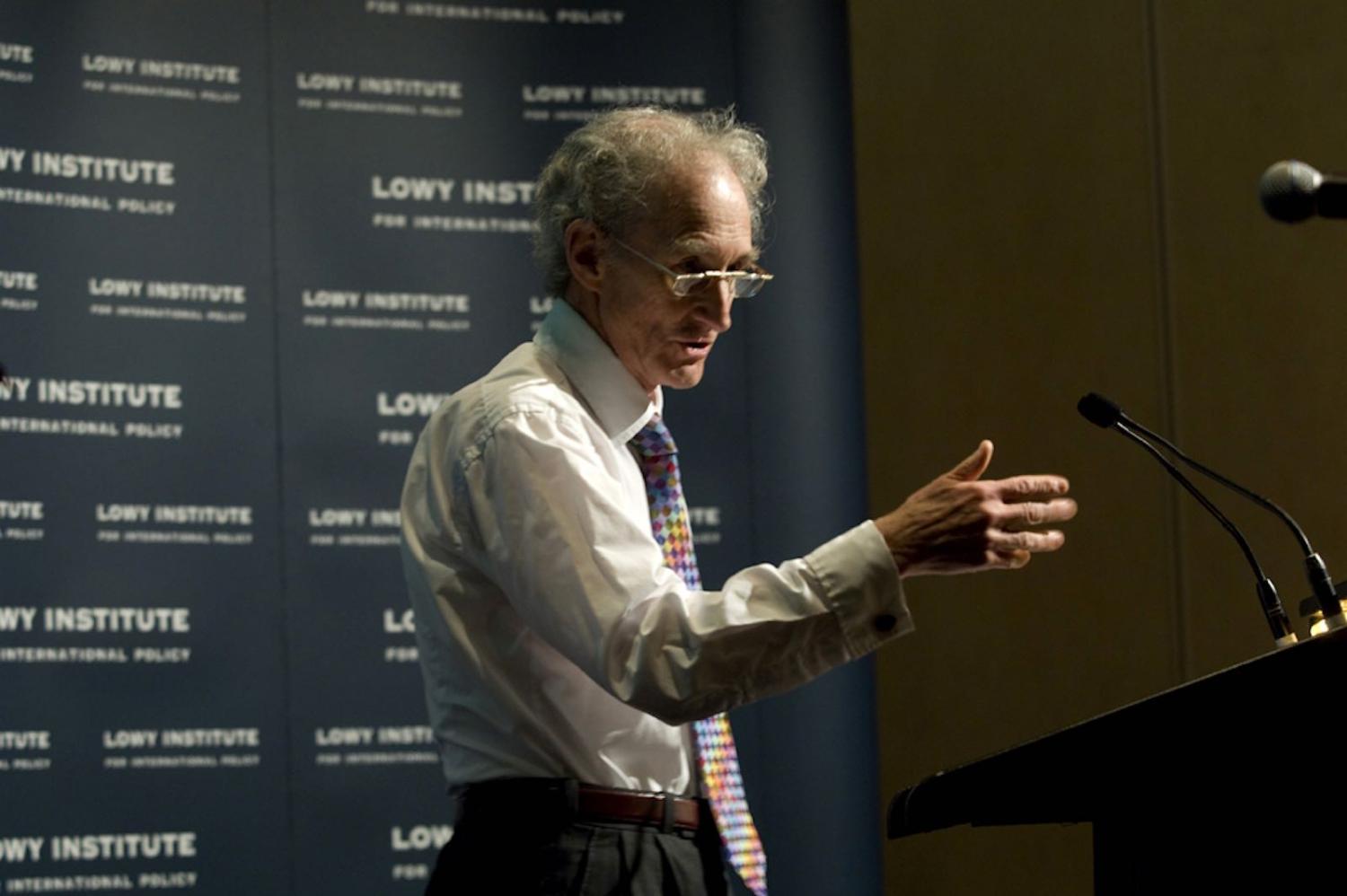

The climate stand-off was outrageously demonstrated when May gave a superb one-hour speech at the Lowy Institute in Sydney. After a scintillating display of the latest evidence from one of the best-informed people on Earth, we were assembled at drinks afterwards. I was talking to Janet Carding, the Cambridge-trained director of the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery in Hobart, when we were approached by David Clarke, then chairman of Macquarie Bank.

“Well,” he said, “all that’s still disputed, isn’t it?”. “By who?” Janet Carding shot back. “Not by anyone who knows their science!”

I can only imagine what Bob May’s riposte would have been. More than just “bullshit” I venture. By coincidence, one of his last projects was in combination with Mervyn King, head of the Bank of England, bringing maths to financial policy.

I shall miss a great friend and a world figure, one of the top Australians of this and last century.