In the midst of Britain’s painful extraction from the European Union, a saga which deepened this week with a second parliamentary defeat for Theresa May’s Brexit deal, key figures on the Conservative right harbour a quiet hope that the Commonwealth will come to the rescue. Notwithstanding the scale of trade between Britain and the EU, they argue that Commonwealth countries represent a natural constituency for Britain. Should a deal with the EU collapse, as looks increasingly likely, Britain will surely have the option of falling back on historic ties with a number of former colonies: Australia, Canada, and India, among them.

Even a century ago, viewing trade in terms of imperial cultural attachments was a stuttering, halting project with more sceptics than backers.

Supporters of a new Commonwealth trade zone are thought to include influential Brexiteers such as Liam Fox and Boris Johnson, current and former ministers in May’s government. The benefits of such a move, say sympathisers, rest on the so-called “Commonwealth effect”, which estimates trade between Commonwealth members to be 20% higher (and costs 19% lower) compared to ties with countries outside the club. This kind of thinking is warmly received by some in Canberra; support for a Commonwealth reboot is firmly implied in former prime minister Tony Abbott’s backing of a no-deal Brexit.

Beyond the confines of nostalgia-tinged conservatism, however, it’s not clear that this vision has many takers. Writing in The Guardian on Monday, another former prime minister, Kevin Rudd, described the plan as “utter bollocks”. True – Australia, Canada, and New Zealand may wish to deepen their trade with Britain. But as Rudd points out, “65 million of us do not come within a bull’s roar of Britain’s adjacent market of 450 million Europeans”. As for India, whose trade negotiations with Australia roll on after a decade, he simply says, “good luck!”

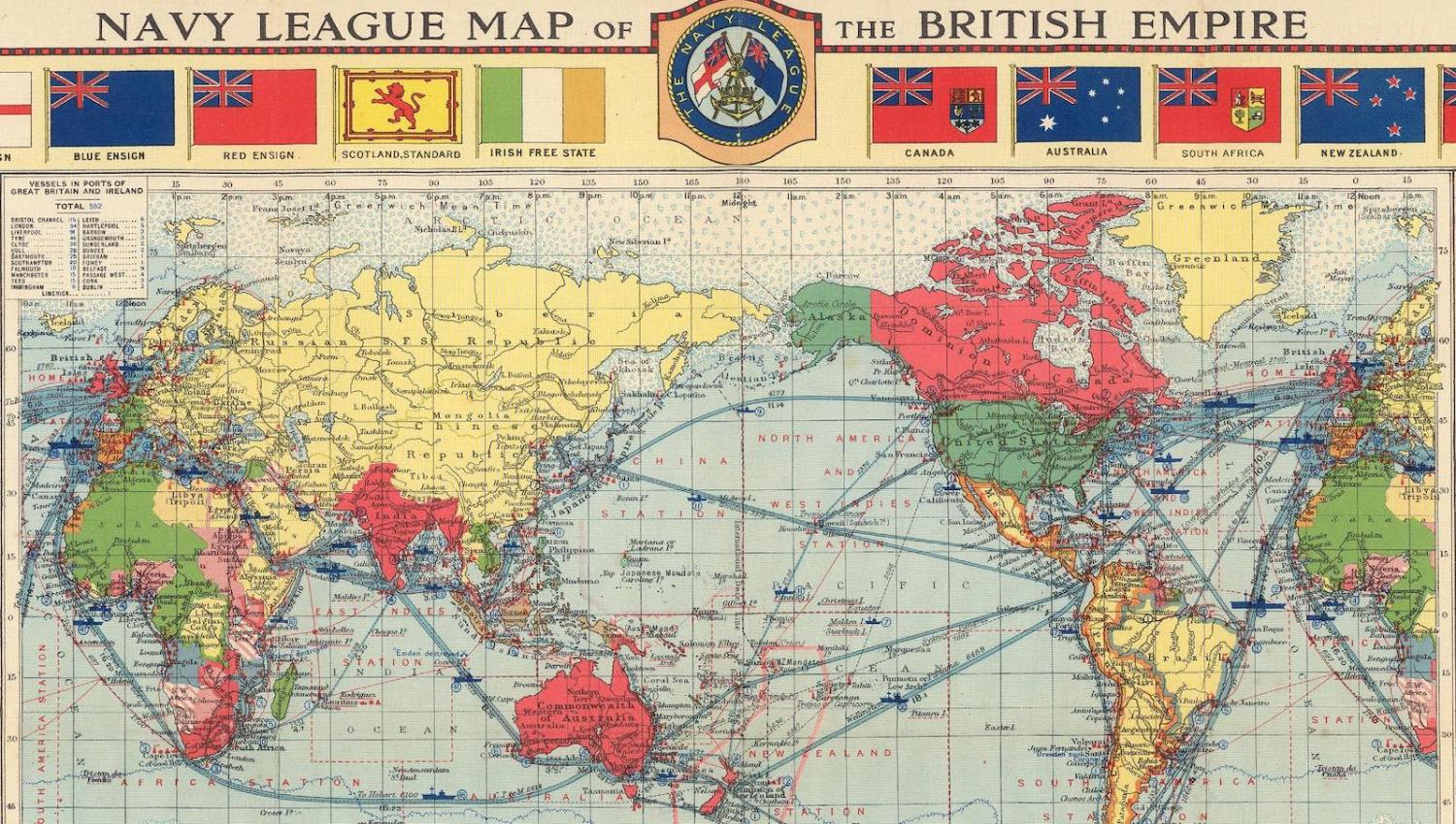

As Brexit enters its final stages, it’s worth remembering that Britain has historic form in this area. Almost exactly a century ago, key figures on the British right, such as Joseph Chamberlain, Lord Willoughby de Broke, and Henry Page Croft, attempted a similar strategic pivot during a time of social and economic upheaval. Then, unlike now, its targets remained (by and large) settler territories of the empire. Just as today, however, its impetus was grounded more in a globe-spanning idea of shared identity than in notions of economic sense.

At the end of the 19th century, many in Britain felt the country’s position was under threat. Internationally, its relative strength was being diminished by the industrial and territorial expansion of rival European powers, and the growing autonomy of settler colonies threatened to push them beyond Britain’s reach. At home, economic change and gradual democratisation had nudged civic life in what many felt were uncomfortable directions. In response, enthusiastic imperialists hatched a plan to forge closer ties between Britain and the empire, with a specific focus on white settler colonies.

Various versions of this blueprint were circulated. Some hankered after an imperial “Zollverein”, based on the customs union pursued by the German states before unification. Others went further, stressing the need for full political integration with the British state. The latter proposal failed to advance beyond the abstract, but the former generated a long campaign in British politics around the issue of “tariff reform”. From 1903 until the First World War, and beyond, groups like the Tariff Reform League fought for the introduction of preferential tariffs between Britain and the colonies.

In spite of some modest successes, including an Australian measure introduced in 1907 by Alfred Deakin, the vision of an imperial customs union was never realised. True free trade was a far-off prospect, but some territories moderated their tariffs to give Britain a slight edge over others. As time went on, however, the wider context failed to pull in the policy’s favour. As historian Andrew S. Thomson has shown, Britain’s share of Canadian imports fell from 54% in 1872–1874 to 21% in 1913; its share of Australian imports from 73% to 52% in the same period; and its share of South African imports from 83% in 1881 to 56% in 1913.

Despite the best efforts of tariff reformers, Britain faced fierce competition in a global marketplace, and other relationships often proved more fruitful for newly independent former colonies. Thus, even a century ago, viewing trade in terms of imperial cultural attachments was a stuttering, halting project with more sceptics than backers.

The present circumstances are significantly changed, but a number of reflections stand out. The first is the seemingly irresistible pull of the empire in British political thought and the long lineage of the “Commonwealth pivot” for Conservatives in particular. It may strike observers as strange that figures like Jacob Rees-Mogg and Boris Johnson rail against Britain’s relegation to a “vassal state” in negotiations with the European Union, while simultaneously invoking histories of colonial hierarchy in imagining the reformulation of the Commonwealth.

Second is the question of whether it isn’t entirely fair for some in Australia and elsewhere to view Britain as something of a “foul-weather friend”, turning to the Commonwealth at key moments of difficulty, but on other occasions happily throwing its lot in with others, as it did upon joining the European Economic Community in 1973.

Finally, it is doubtful that, any more than a century ago, a retreat to the safety of the Commonwealth offers realistic respite for Britain as it breaks ties with Europe. What new ties it forms remains to be seen.