Australia’s late entry into the offshore wind market is a welcome development for clean energy advocates. The federal government this month issued what it has called the first round of feasibility licenses to six companies to explore offshore wind farm projects off the coast of Victoria.

Yet amid this promising development, the scarcity of undersea power cables poses a looming challenge for the industry – not just their installation, technically difficult as that can be, but also their protection.

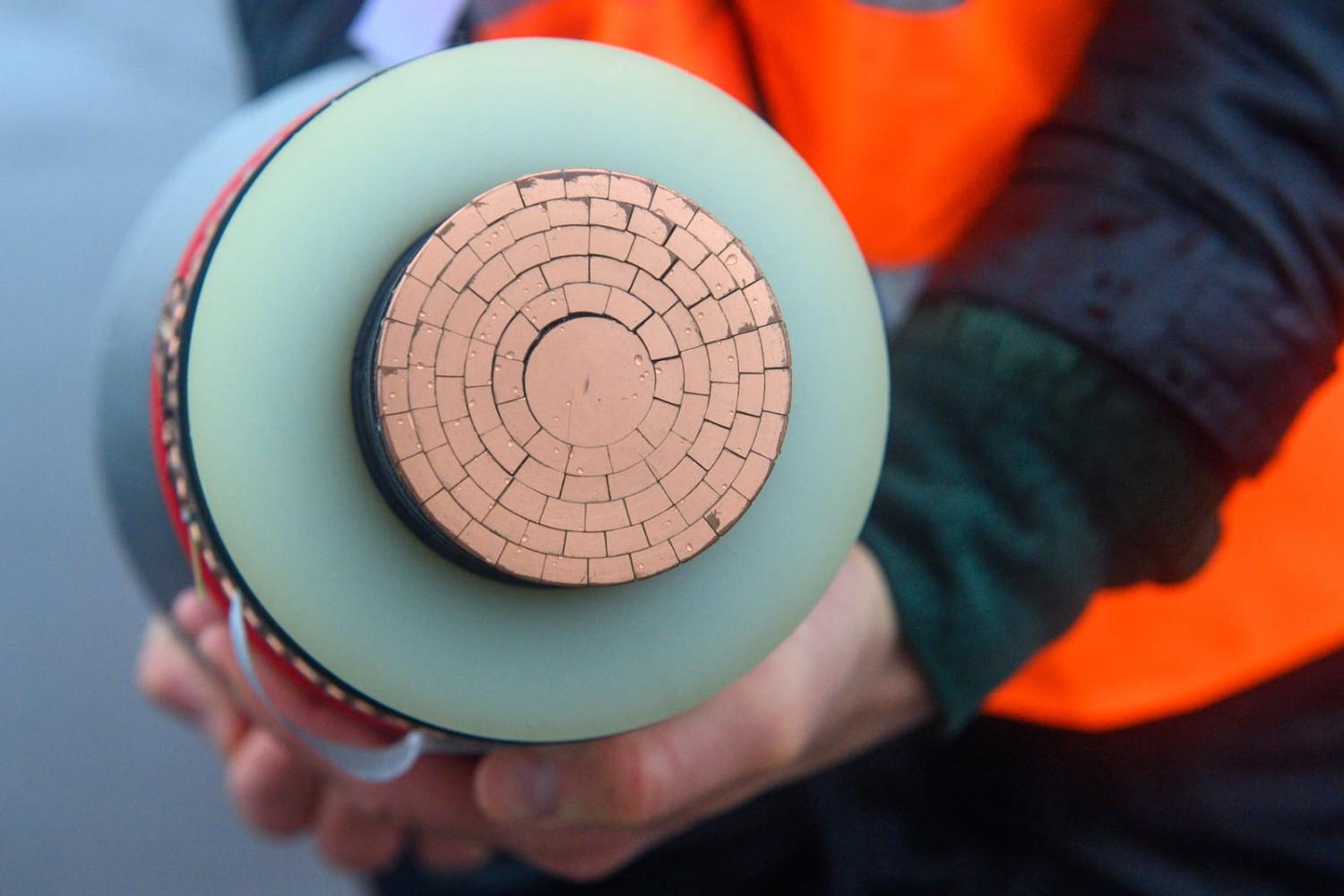

Unlike telecommunications or data cables, which now receive considerable attention due to their role in the intensifying US-China technological competition, the security implications of submarine power cables connected to offshore wind farms are often overlooked. Converting wind energy into electrical power requires a network of high-voltage direct current (HVDC) submarine cables and substations that facilitate the transmission of electricity over long distances from the turbines to the shore. From onshore substations, the electricity is then fed into the existing grid for distribution to consumers.

Unlike underwater data cables, the prospect of cyber security threats to submarine power cables does not immediately spring to mind, however the danger is still apparent. Offshore wind farms can be vulnerable due to their remote location and complex communication systems required to operate safely. Unlike onshore wind farms, those located at sea require extensive digital infrastructure to connect with onshore systems, maintenance vessels or drones, which increases the potential risk. In the United States, offshore wind farms are increasingly viewed as a national security concern. The reliance on critical components sourced from China for turbine manufacturing further highlights the intricate interplay between energy and security.

But these geopolitical considerations are secondary to the immediate challenges facing the offshore wind farm industry. A global surge in wind projects has intensified demand for cables, with forecasts indicating this could double by 2030. Three European companies – NKT (Denmark), Prysmian (Italy), and Nexans (France) – dominate 75% of the HDVC market. However, the Financial Times noted recently that production capacity for most submarine power cable manufacturers is fully booked until the late 2020s. This could see countries other than China face HVDC cable shortages. China has managed to avoid cable shortfall issues having devoted substantial resources to bolstering its HVDC sector over several years. Additionally, China boasts homegrown companies that predominantly cater to the domestic market.

Moreover, technological needs further compound the problem, as larger, longer, and higher-voltage cables are required for bigger and more distant offshore wind farms. Upgrades to manufacturing equipment and bespoke cable production can exacerbate supply chain challenges. The looming shortage of cables not only threatens project timelines but also raises concerns among insurers, driving up premiums and leaving projects without cover.

Then there is the challenge of laying the cables. Only a limited number of vessels exist that are capable of laying, repairing, and maintaining these cables – a little over 60 such ships operate worldwide, the majority of which are aging. This shortage hinders the progress of offshore wind farm developments. And with competing priorities around the installation of data submarine cables, there can potentially emerge competition between data and HVDC submarine companies as both sectors experience growth in demand.

This competition underscores the broader challenges facing the offshore wind industry and highlights the need for careful planning and collaboration to address capacity constraints. For Australia, a commitment to green energy will require government support and effective collaboration with private sector to avert potential cable shortages in the industry, as well as managing the availability of ships able to lay down the lines.

The need is urgent. This could be considered as part of the government’s drive for a “Made in Australia” industry policy, emphasising the importance of domestic manufacturing and job creation. Moreover, it aligns with a broader global initiative aimed at ensuring fair competition and fostering collaborative efforts among nations transitioning to sustainable energy sources. By actively participating in this global push, Australia can not only strengthen its renewable energy sector but also contribute to the collective global goal of combating climate change. These cables will be an essential infrastructure network, can help Australia propel its renewable energy agenda at home and also support clean energy development for the broader region.