Australia is yet to adequately grapple with the unique challenges that critical seabed infrastructure protection poses to its defence and national security.

In Europe, recent critical seabed infrastructure incidents have rattled leaders. Nord Stream and Balticconnector have entered the public lexicon as examples of vulnerability. In May 2023, NATO’s intelligence chief David Cattler warned of “heightened concerns that Russia may target undersea cables and other critical infrastructure in an effort to disrupt Western life.” Cattler went on to say this could be an effort to gain leverage against those nations providing security to Ukraine, adding “the Russians are more active than we have seen them in years in this domain.”

Around the same time another NATO official private expressed suspicions that “somewhere in Moscow there are people sitting and thinking of the best ways they can to blow up our pipelines or cut our cables.”

Cables carry approximately 98% of data communication globally.

And it is not just in Europe where the alarm has sounded. Cut cables at Taiwan’s Matsu Islands and incidents in the Red Sea have prompted capitals to consider defensive actions. The isolation that is inherent to much of this infrastructure has allowed claims that cables have been inadvertently damaged. Yet as analyst Elisabeth Braw has warned, “given the world’s dependence on the cables and the few ships that can service them, the near future offers tempting prospects for any country ready to create a few more “accidents” at sea.

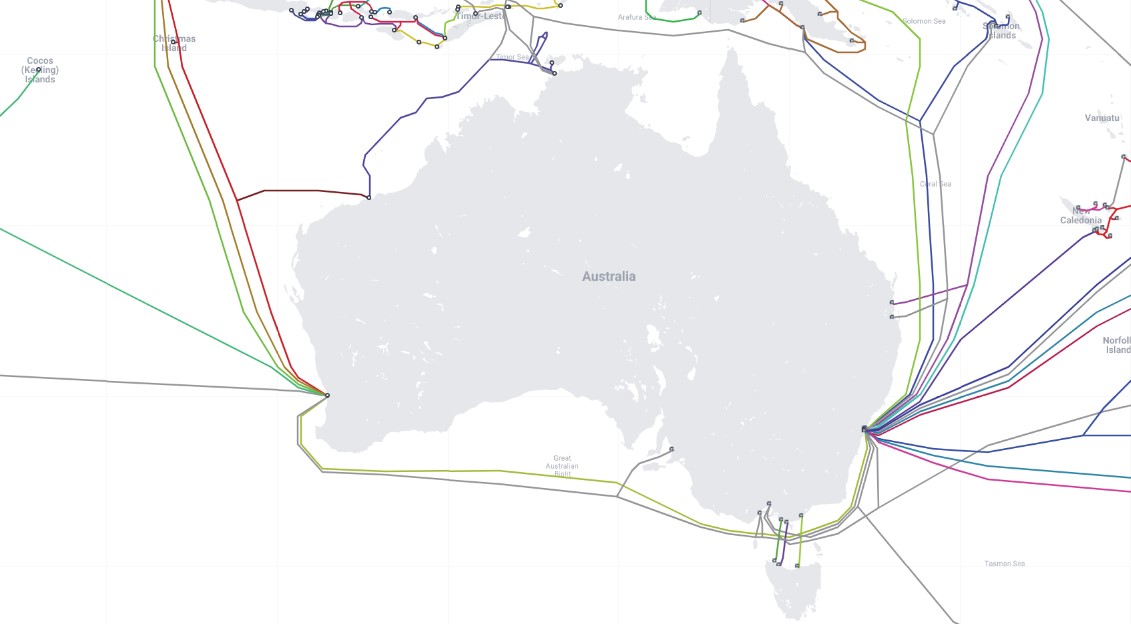

While the seabed hosts a range of critical infrastructure, the most important to modern society are submarine cables. These cables carry approximately 98% of data communication globally. The 500 plus submarine cables which transit the globe carry all manner of data, including private communications (e.g. email and messaging services), banking data, stock market data, medical data, scientific data, government communications, traffic between data centres, and video streaming.

These seabed lines of communication are understudied and underappreciated, particularly in Australia.

New diplomatic initiatives, including Australia’s new Cable Connectivity and Resilience Centre and the Australia, US, Japan Trilateral Partnership or Infrastructure Investment in the Indo-Pacific have been launched to improve cable resiliency regionally, and Australia is a leader in submarine cable protection zones.

However, more steps are available to Australian defence policymakers to address the threats associated with protecting critical seabed infrastructure.

- Talk about the risks, publicly

Australia’s defence and maritime security strategies, the unclassified versions at least, are by-and-large silent on critical seabed infrastructure protection. Integrating this issue into a wider discussion is a crucial first step to building Australian society’s resilience. - Define a response

When a potentially hostile seabed incident occurs, as well as swiftly repairing the damaged infrastructure, urgent investigations must ensue to identify the culprit and attribute the incident. In bureaucratic terms, this means establishing incident response governance. This could be facilitated by a new coordination organisation within the Royal Australian Navy or the Department of Home Affairs to guarantee oversight and coherence.

As an island nation, Australian reliance on this underwater infrastructure cannot be avoided.

- Be ready

Australia needs to acquire platforms and capabilities to monitor and protect critical seabed infrastructure. Such capabilities include underwater vehicles and sensors. Australia’s new ADV Guidance could play an important role in protecting seabed lines of communication, as Britain’s similar ships do, although whether such a role yet exists has not been publicly disclosed. As Cynthia Mehboob noted in The Interpreter recently, “Only a limited number of vessels exist that are capable of laying, repairing, and maintaining these cables”. Further, it also means ensuring that anti-submarine warfare capabilities are also capable of protecting critical seabed infrastructure. - Private-public partnerships

Most critical seabed infrastructure is owned, operated and repaired by the private sector, so this makes coordination with government essential. The submarine cable industry is comprised of many players, and often submarine cable networks are owned by consortia of firms. While industry prioritises a fast, secure and stable data conduit, industry is not as aware of geopolitical nuances, emerging maritime threats and advanced grey-zone tactics now employed in Europe and the Indo-Pacific. - Working with global partners

International coordination is essential. The Quad, AUKUS and multilateral forums are already an opportunity to work together, and Australia is establishing its Indo-Pacific Cable Connectivity and Resilience Centre. However, these initiatives are largely diplomatic not defence led. Further, as analysts have observed, the international legal regime for submarine cables is patchy.

Seabed lines of communication cannot be taken for granted. And as an island nation, Australian reliance on this underwater infrastructure cannot be avoided so must be protected.

This article draws on findings in a research article “Defending Seabed Lines of Communication” recently published in the Australian Journal of Maritime & Ocean Affairs. These articles were written and received funding as part of the author’s Non-Residential Fellowship with the Royal Australian Navy’s Sea Power Centre – Australia. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the Royal Australian Navy or any other organisation.