Despite their other disagreements, several fans and critics of Clive Hamilton’s Silent Invasion: China’s Influence in Australia converge around the claim that his comments on national sovereignty are overstated. The Chinese Government’s influence operations, we are assured, do not impinge on Australian sovereignty.

If only that were so.

True, few of Beijing’s influence operations touch on issues that worry Australians when they usually think about sovereignty. Indigenous sovereignty does not arise, or the question of repatriating sovereignty from Buckingham Palace. Territorial sovereignty is not at risk. And Beijing’s operations have little bearing on the perennial question of “who says who comes in”, often regarded as the highest affirmation of national sovereignty in Australian public life.

If Beijing has a view on these matters it is keeping them to itself.

Beijing’s influence operations do, however, touch on parliamentary sovereignty. China’s Communist Party (CCP) seeks to interfere in electoral systems everywhere. It has the will and the capacity to interfere in Australian electoral and parliamentary processes. This is not a trivial matter.

For a party that has no interest in introducing popular elections into its own jurisdiction, the CCP shows remarkable curiosity about electoral democracies elsewhere. The point is not to emulate them but to exploit them. Through its United Front Work Department (UFWD), the party seeks to mobilise Chinese overseas to participate in democratic elections to advance the party’s strategic objectives and China’s national interests.

This plan is presumptuous on several counts. It assumes that the primary loyalties of Chinese Australians or Chinese Canadians lie with China rather than with Australia or Canada. Further, it assumes these electors are incapable of making sensible electoral choices without organised prompting from Beijing.

And it assumes the party can intimidate foreign political leaders contesting hard-fought elections into yielding to Beijing’s demands simply by threatening to mobilise ethnic Chinese citizens of those countries to vote in favour of Beijing’s preferred candidates and policies.

Each of these assumptions is clearly spelled out in recent party documents and official statements.

The first is that all Chinese overseas, of every nationality, should help achieve the political objectives of Xi Jinping’s “China Dream of National Rejuvenation” in relation to the South China Sea, Taiwan, and the Belt and Road Initiative. This is spelt out in Xi’s own words and duly implemented by the UFWD.

In October 2017, UFWD officials described their overseas mission as “winning the hearts of overseas Chinese” to realise the China Dream, repeating the leadership’s claim that “all Chinese sons and daughters at home and abroad are striving to realise the China Dream” and “oppose ‘independence’ and advance reunification”. Through its influence operations in Australia, the UFWD tries to ensure this is so.

The second presumption is that ethnic Chinese citizens of liberal democracies need to be encouraged to vote and stand for office on China’s behalf. New Zealand specialist Anne-Marie Brady has identified a specific United Front strategy adopted under Xi’s leadership that encourages Chinese overseas to participate in electoral and party processes in their home countries as candidates, donors, and voters to advance China’s national interests abroad.

These efforts are supplemented in Australia by United Front media training programs in China offered to ethnic Chinese journalists from abroad. The party manages a vast propaganda alliance of ostensibly independent schools, cultural organisations, and news and current affairs platforms around the world.

The party recently claimed its global network is “standardising” teaching in 20,000 Chinese language schools abroad and connecting 530 journalists and media entities overseas into a Global Chinese Language Media Alliance supporting United Front foreign policy objectives. A number of Chinese-Australian media operators have been drawn into the network. The lessons they take home about using Chinese community media to exploit vulnerabilities in their national electoral systems can be inferred from the stories they publish on completing their training.

Third, Beijing presumes that these efforts have given it the capacity to mobilise ethnic Chinese votes in Australia. Former security chief Meng Jianzhu was reported to have said on a visit to Australia last year:

it would be a shame if Chinese Government representatives had to tell the Chinese community in Australia that Labor did not support the relationship between Australia and China.

Meng’s cynical confidence in swaying Australian voters is probably misplaced. Still, there could be no clearer indication of Beijing’s intention to compromise Australian parliamentary sovereignty.

The risk of compromise arguably goes beyond interference in electoral politics. Sam Dastyari’s fall offered salutary lessons for elected members who might have been tempted to accept political donations in return for doing favours for foreign powers.

But one vulnerability that remains is the practice of political parties making parliamentary appointments to upper houses of state and federal parliaments, without public election, when a seat falls vacant outside of an electoral cycle.

It is not difficult to imagine a scenario in which a sitting member is offered a financial inducement by a party donor, acting on behalf of a foreign power, to step down and create a vacancy to be filled by appointment of a pro-Beijing (or for that matter pro-Washington) lobbyist associated with the donor.

What is to stop it? A pea and thimble trick of this kind would not breach Australian law or fall within the remit of agencies charged with policing abuses of parliamentary privilege to correct it. The case would probably not even come to light. In face of Australian defamation laws, no journalist could report a breach of this kind without fear of punishing defamation penalties.

The UFWD is in a position to take advantage of vulnerabilities in Australian parliamentary practice, confident that defamation law is on its side, that plausible deniability is assured, that its own documentation is classified as secret, and that betraying state secrets is an offence punishable by lengthy jail sentences or possibly execution in China.

Does this matter? Yes. The convulsions shaking America as a result of covert Russian interference in US elections have alerted people everywhere to the consequences of foreign interference in democratic electoral systems.

Would it involve racial profiling? No. The problem lies not with Chinese Australians, who can vote as they please. It is the CCP’s overt and covert interference in Australia’s parliamentary sovereignty that is the proper focus of censure and countervailing action.

Can the problem be remedied? The CCP will not budge, but Australians can legislate around foreign donations, covert interference, and defamation, and monitor the everyday conduct of political parties without fear or favour.

Is this too much to ask in defence of parliamentary sovereignty?

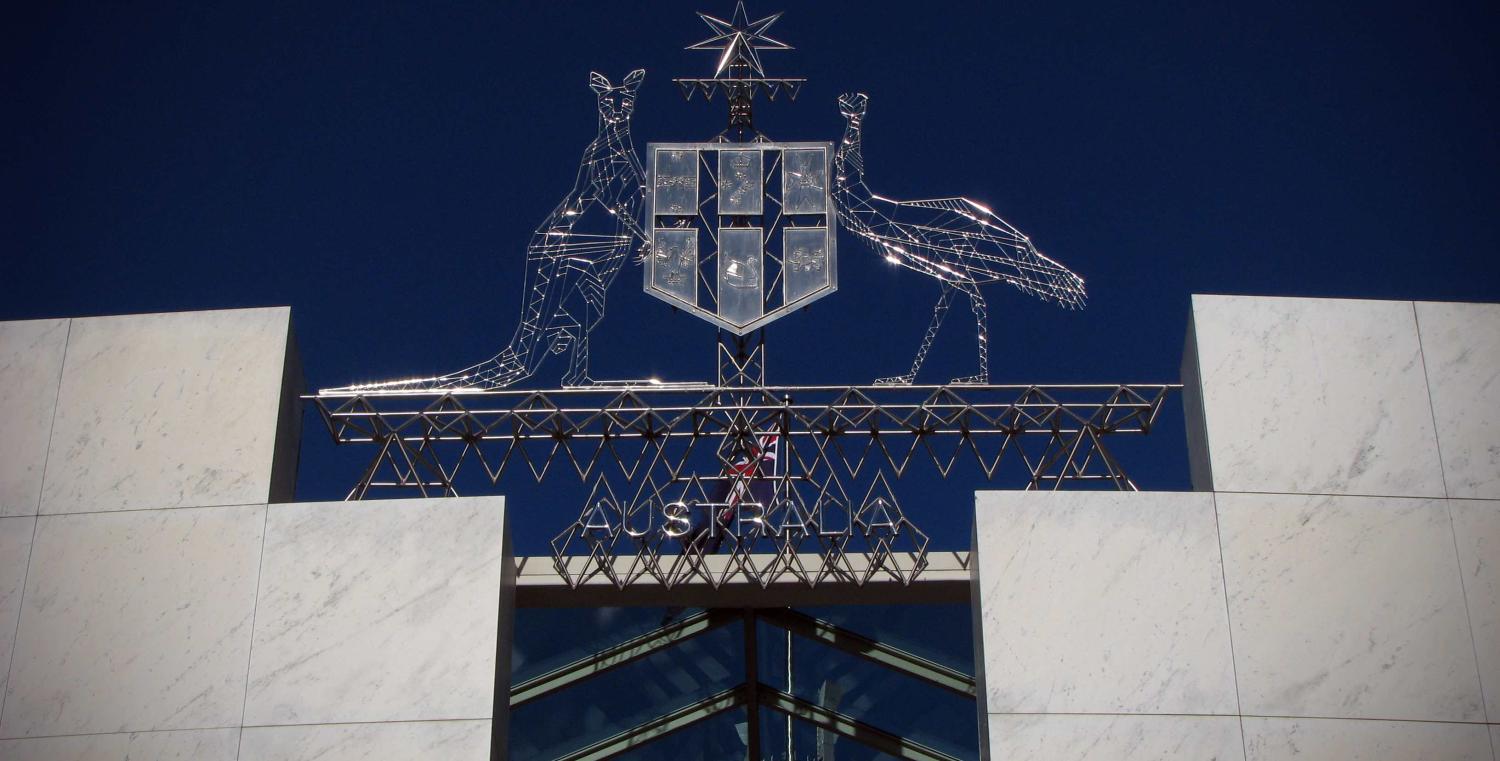

Photo via Flickr user Eduardo M. C