“Debt trap” diplomacy has been a recurrent rallying cry for critics of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and its overseas infrastructure lending activities. Over the past two years, this debate has taken centre stage in the Pacific, with China accused of drowning these tiny economies in unsustainable mountains of debt.

In the vortex of geopolitics, however, objective analysis has been missing from the debate. Our latest Lowy Institute report has sought to fill this gap, drawing upon the unique dataset contained in the Lowy Institute Pacific Aid Map and combining it with other data to provide an evidence-based assessment of the impact of Chinese loans on Pacific debt sustainability and the risks posed in the future.

The problem is not that China’s lending is overly skewed towards countries already at risk of debt problems. Rather, it is the sheer scale of lending, combined with inadequate controls to avoid potentially unsustainable loans.

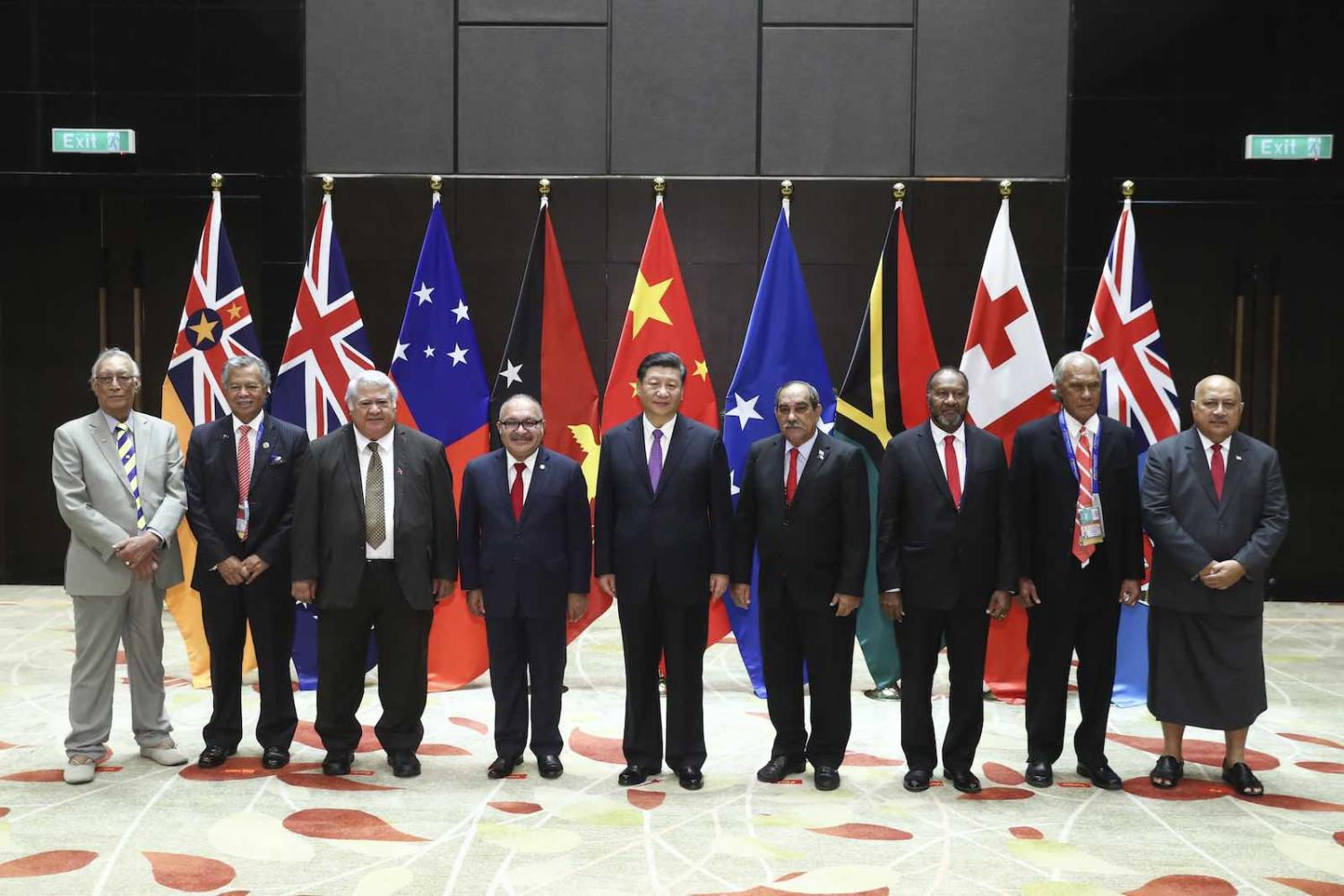

The Pacific is a central part of the global story surrounding China’s BRI. Our research shows that the small and fragile economies of the Pacific are among the most vulnerable to potential debt problems, while several Pacific countries already appear to be among those most heavily indebted to China anywhere in the world.

Nonetheless, our analysis suggests that China’s lending practices in the Pacific have not be so problematic as to justify accusations of debt trap diplomacy – at least not yet.

According to the regular assessments by the International Monetary Fund, debt sustainability risks are indeed rising in the Pacific, but this reflects a confluence of factors and is more closely linked to the region’s high exposure to disasters, rather than excessive Chinese lending.

Nor has China suddenly become the dominant financier in the region and therefore able to exercise significant leverage over Pacific nations. Traditional creditors (i.e., major domestic banks, Japan, the Asian Development Bank, the World Bank) still play a more significant role, especially if much larger amounts of grant aid are also considered. The exception is in Tonga, where China holds over half of public debt. But this has not exactly been an advantageous position – China has twice agreed to deferring repayments, while getting little in return.

China’s lending terms are also hardly predatory. Whereas its overseas lending in many other parts of the world often comes at market rates, China appears to have been much more careful in the Pacific, with the vast majority of its loans having been concessional enough to qualify as aid, according to the standard of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Perhaps the most important question is whether China has been lending to countries already facing elevated debt risks. Our research found that in 90% of cases, Chinese loans were made in situations where there appeared at the time to be scope to absorb such debt sustainably. That leaves 10% of cases where Chinese loans looked problematic, but in comparison to other official lenders in the region, this figure would not make China a huge outlier.

The problem is not that China’s lending is overly skewed towards countries already at risk of debt problems. Rather, it is the sheer scale of lending, combined with inadequate controls to avoid potentially unsustainable loans.

Hence, looking ahead, we see clear risks. In particular, our analysis shows that, under a business-as-usual scenario, several Pacific countries (most notably Vanuatu, Samoa, and Tonga) would quickly enter risky territory in terms of their overall burden of debt.

Pacific nations are clearly in the driver’s seat in setting their own borrowing policies. Most have frameworks intended to protect overall debt sustainability, operating with varying degrees of effectiveness.

China also has a role to play. Ultimately, China cannot remain a major player in the region through its current model of cheap loans without eventually fulfilling the debt trap accusations of its critics.

To avoid this, China will need to substantially restructure its approach – in particular by adopting clear sustainable lending rules and, ultimately, focusing far more on grant aid rather than loans.

Positively, China has begun taking debt sustainability more seriously, in particular by signing up to G20 principles and guidelines, which include commitments to key global standards for sustainable lending.

But China is still moving in baby steps. For instance, a new debt sustainability framework released earlier this year by China’s finance ministry remains a “non-mandatory policy tool”. It needs to become a mandatory one for China’s Export Import Bank – which leads China’s overseas lending in less developed countries – and linked to clear lending rules aimed at protecting the debt sustainability of borrowing countries.

Adopting such rules is exactly what the Australian government has done with its own new bilateral infrastructure lending facility for the Pacific, giving more confidence that its activities will remain sustainable.

Clear, sustainable lending rules would bring China up to speed with other official sector lenders. It would also give China far more international credibility that it is indeed acting as a responsible global power.