China is sparing no efforts in promoting the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which, as Beijing claims, aims to enhance regional connectivity between China and countries in Asia, Africa, Europe, South America and even the Pacific.

The role for SOEs is a two-way process. SEOs could affect China’s policy making on the BRI while receiving policy guidance from the state.

Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) are the main participants in this ambitious program and are playing a leading role in implementation. As of October last year, Chinese SOEs contracted about half of BRI projects by number and more than 70% by project value. So understanding the BRI from the perspective of SEOs is useful.

The BRI has a combination of strategic and economic considerations. Both are highly relevant to Chinese SOEs. The strategic objective of the BRI is to secure a favourable international environment to facilitate China’s economic development. Back in November 2002, the 12th National Congress of Chinese Communist Party declared that the first two decades is “a period of strategic opportunity” (zhanlue jiyuqi) of which China must make full use to further increase its economic strength.

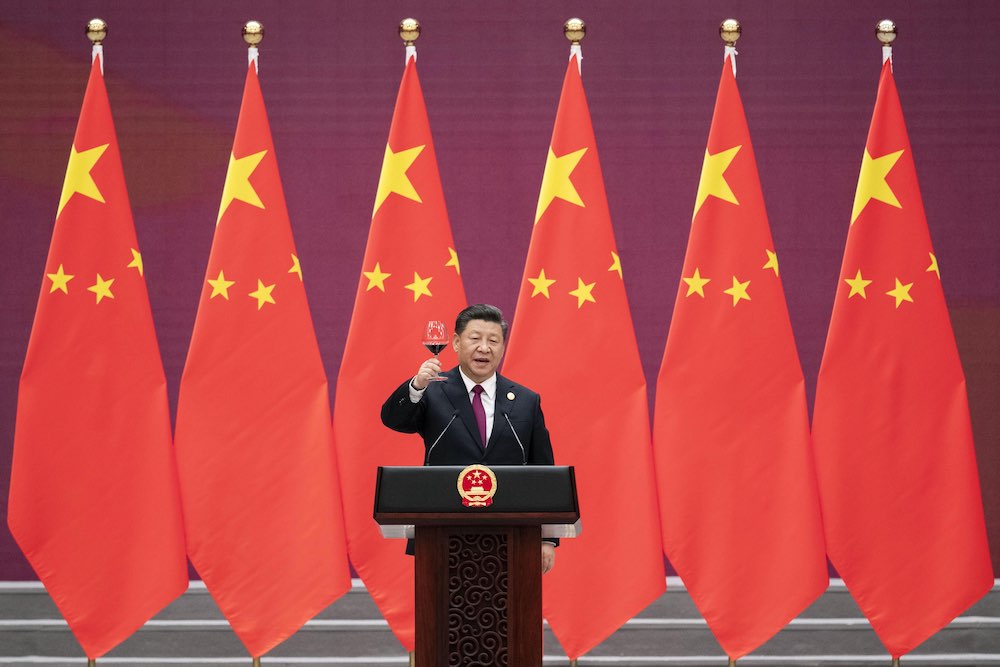

Fast forward to 2017, and Chinese President Xi Jinping’s speech at the 19th Party Congress, he remarked that “China is still in an important period of strategic opportunity for development”. In this context, BRI was designed by the Xi Jinping administration to maintain a favourable external environment by promoting economic integration between China and partner countries. As Chinese official media Xinhua reported, the BRI is to support the building of “a community of shared interest, shared responsibility and common destiny”.

Linking the BRI to the concept of community of common destiny, which is Xi’s major diplomatic concept, clearly demonstrates that the BRI is part of China’s grand diplomatic strategy. A Leading Group for Promoting BRI headed by Vice Premier Han Zheng and consisting of senior officials oversees BRI implementation, with the support of a subsidiary office located within China’s National Reform and Development Commission.

Chinese SOEs are given the job of supporting the state to achieve the strategic objective of the BRI. They are the main representatives of the state in China’s economic diplomacy which aims to “yijing cuzheng” (use economics to promote politics) and “zhengjing jiehe” (combine politics and economics), and have gained rich experience in conducting economic activities overseas, especially in developing countries in Africa, Asia, Latin America and even island countries from the Caribbean and the Pacific.

Economic interest is another main consideration for the Chinese government and SOEs in promoting the BRI. This could be seen as a continuation of China’s “going out” (zou chu qu) strategy. Introduced in the late 1990s, this strategy was designed to support Chinese enterprises especially SOEs in expanding overseas markets and obtaining access to resources and raw materials to fuel China’s fast-growing economy. Clearly, the BRI will provide more opportunities for Chinese SOEs in this regard.

Another widely acknowledged motive of China is to send the excess industrial capacity of SEOs offshore. SOEs will benefit from the BRI to sharpen their competitive edge in the global market. As Xiao Yaqing, then Director of State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission, the overseer of Chinese SOEs, said in May 2017, the Chinese government has pledged full support to SOEs in implementing the BRI, ranging from policy to performance evaluation, risk management and analysis. The state’s emphasis on SOEs is also revealed in China’s official policy for BRI implementation, that is “government-led, enterprise [mainly SOEs]-oriented and market-based”.

A major area of opportunity for Chinese SOEs is infrastructure, which was highlighted at the second BRI Forum held in April in Beijing. The BRI is currently framing China’s relations with partner countries, which are likely to receive more aid and non-aid financial support from China. For example, BRI was a central theme of the meetings between Xi and his counterparts from all the eight Pacific island countries that recognise Beijing on the margins of APEC summit held in Port Moresby in November 2018, and Xi pledged to further support the island states. All these countries signed up to the BRI by November 2018. Tonga was even granted another five-year extension for due debts to China after the Pacific state joined the BRI.

The role for SOEs is a two-way process. SEOs could affect China’s policy making on the BRI while receiving policy guidance from the state. The ways for SOEs to wield influence include voicing views at state-organised BRI forums, providing advice when groups from government agencies visit SOEs for BRI research, writing internal references for the government, and publishing policy reports on BRI. Sometimes, the personal links between SOE directors and government officials could be important in influencing government policies.

In the implementation of BRI, the “principal-agent dilemma” could occur and has been observed in Chinese SOEs’ previous operations overseas. This means while the state as the principal favours China’s overall national interest, the enterprises as BRI implementation agent tend to prioritise their own economic interest. This may override the state’s considerations, such as diplomatic interest and image building during times of conflict. This could be more evident in the future if China pushes for “the separation of government administration and enterprise management” to increase SOEs’ competitiveness.

BRI also faces other constraints such as the differences in political and economic systems between China and many partner countries, risks of political disturbance in countries such as Venezuela and Ethiopia, concerns of debt issues and the lack of high-quality professionals. In all, the future of BRI is uncertain, but the state-owned enterprises are actors best considered.