Following the deadliest terror attack in New Zealand’s history, a flood of articles have been devoted to “understanding” the accused shooter, Brenton Tarrant, decoding his manifesto, and finding reason in his actions. Yet such assessments overlook a deeper, more chilling reality: Tarrant’s alleged attack was never so much about the violence itself as it was about entertaining his online community of fellow “trolls” with the spectacle of death.

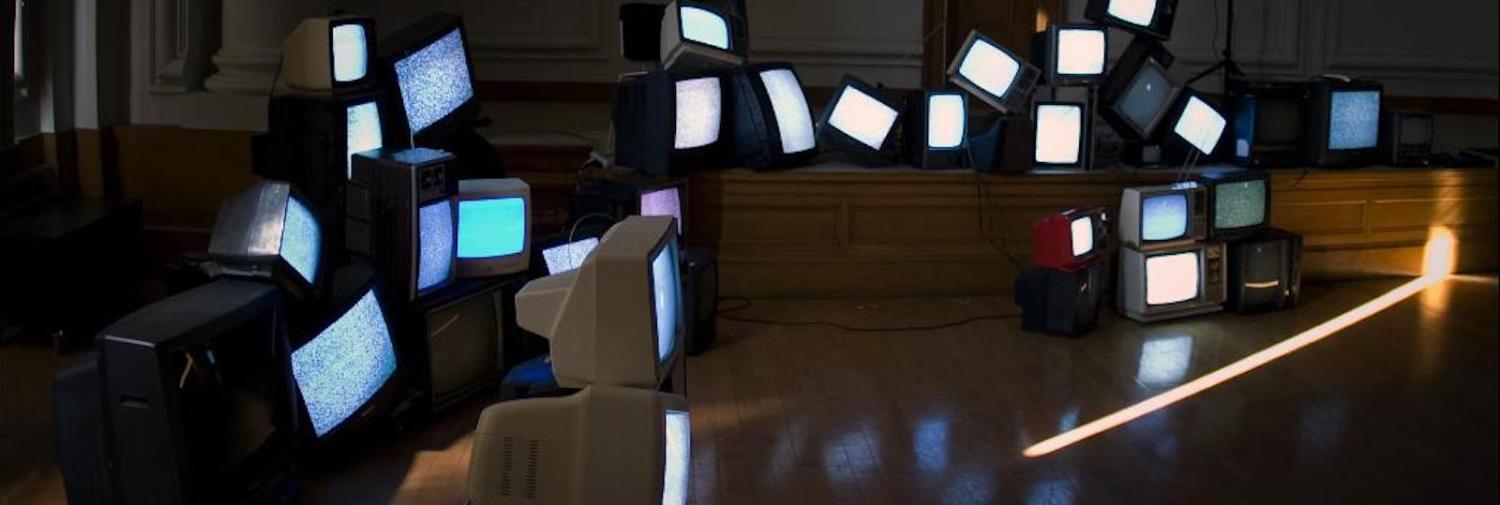

Indeed, I would argue that the Christchurch attack – staged, commentated, and live-streamed to the internet – marks the point at which terrorism has crossed into live performance.

Tarrant’s theatrics cannot simply be consigned to the depths of the internet. Doing so will allow them to become a subject of morbid exoticism and, to some, fascination.

As police were quick to advise in the aftermath, Tarrant’s broadcast and manifesto should not be circulated or shared. However, Tarrant’s theatrics cannot simply be consigned to the depths of the internet. Doing so will allow them to become a subject of morbid exoticism and, to some, fascination. The best way to counter the dark appeal of Tarrant’s actions, obscene as they were, is to understand and contextualise them within a broader analytical framework.

Tarrant’s broadcast and manifesto were littered with online in-jokes and references to fringe internet culture. These included allusions to YouTube figure PewDiePie, listening to Serbia Strong and Initial D in his car, and claiming that Candace Owens is the primary figure responsible for his radicalisation, while with apparent sarcasm claiming he does not agree with her more “extremist positions”.

Seen together, these aspects all hint at a word otherwise unfamiliar in the realm of terrorism: irony.

Rather than defining the cause and motivation for the attack, these references were intended as “easter eggs” to maximise its “entertainment value” of the attack for those familiar with their meaning. The media’s difficulty in coming to terms with them simply prolongs this entertainment value to the target audience.

While the specific motives and intentions will likely be determined over the course of a criminal investigation, the attack warrants particular attention for quite pointedly seeking to marry mass killing with fringe internet humour.

While ISIS can be credited with popularising the concept of “terrorism as entertainment” and the livestreaming of small-scale attacks (“dying live”), Tarrant’s broadcast differs from their model in a number of ways. Most importantly, while the broadcasts from ISIS sought to glorify the “lions of Islam” fighting for the Caliphate and inspire others to follow their example, Tarrant seems to have intended to thrill and amuse his audience by interspersing references to fringe internet culture amid scenes of mass killing.

Having apparently flagged his intention beforehand with an anonymous posting to 8chan, a site renowned for extremist views, Tarrant’s broadcast was intended as a quasi-comedic performance for his target audience. Complete with blithe monologue, entirely incongruent with the severity of its context, Tarrant’s first-person broadcast was intended to entertain his audience by immersing them in the obscenity of violence.

During the massacre, other anonymous posters cheered Tarrant on, hailing him for translating their online hatred into real-world action, and urged more to follow the example.

The various names, dates, and historical events daubed on Tarrant’s multiple guns and magazines, ranging from historical battles between Christian and Muslim armies to modern white nationalist killers such as Alexandre Bissonette and Luca Traini, as well as recent victims of Islamist terror attacks such as Ebba Åkerlund, make clear that Tarrant wanted to locate his actions as a continuation of what he saw as a clash of civilisations. It was also a stylised attempt to offer ritual significance to his violence.

The particularities of Tarrant’s attack are by no means insignificant. In this form of terrorism, radicalisation takes place under a veneer of entertainment and humour plays an important role in desensitising the viewer to the horror of what is being portrayed. The fact that real human beings are being killed is concealed by euphemistic memes and grand narratives of cultural conflict.

It is difficult to know where Tarrant’s model of terrorism will lead. At worst, it will open the door to a competition of one-upmanship between online figures seeking to “outperform” their fellows in terms of the gore, dark humour, and obscenity of the content they produce.

The fact that Tarrant was speaking to a crowd that not only found entertainment in his actions but cheered him on and called for more suggests that violence, for these figures, is already inconsequential. Whether their perceived enemies live or die makes no difference so long as they can share the thrill of killing with their fellows.

For the moment, these figures seem comfortable venting their frustrations to a like-minded community online. However, it’s not impossible that Tarrant has set an example that others will seek to follow.