An ill-fated business deal, a major corruption case, and protestations from Beijing about the visit of a dissident made the year 2009 something of an annus horribilis for Australia’s relations with the People’s Republic of China. It also marked the collapse of the Labor–Liberal Coalition policy bipartisanship that had, for the most part, ensured stability and continuity in this country’s relationship with a nettlesome trading partner and burgeoning regional power.

For me, however, the latest wave of bilateral disquiet really started on the eve of 24 April 2008, the day China’s Olympic Torch relay reached Canberra.

Beijing was to host the summer Olympics that August and, in the lead-up to what many hailed as China’s global “coming-out Party”, the Olympic Torch was making a 129-day, 137,000-kilometre trek during which numerous torchbearers would carry what the Chinese dubbed the “sacred flame” through countries on all continents and through every province and region.

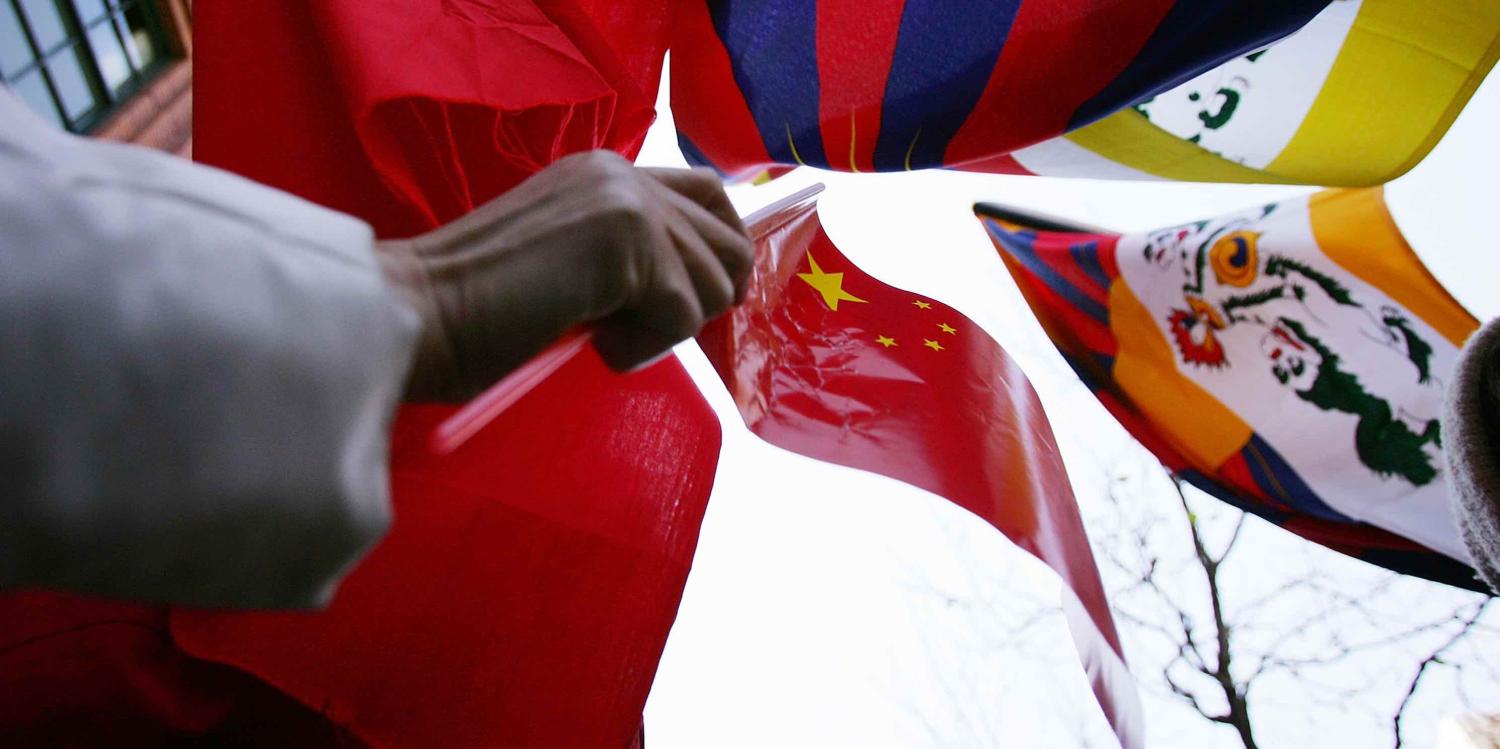

Violent state repression of a bloody uprising in Tibetan China shortly before the relay started had turned the progress of this symbol of international unity into a source of contestation and protest.

When torchbearers were harassed on the Paris leg of the relay, Xi Jinping, a member of the Chinese ruling Communist Party’s Politburo in charge of Olympic security, gave a secret speech warning about international plots against China and the need for vigilant patriots to protect the torch, the symbolic embodiment of China itself.

A friend leaked a copy of Xi’s speech to me. It was redolent of Chinese Cold War rhetoric, common since the repression of mass protests against party autocracy in June 1989. Now, however, this was a struggle without borders.

In the preface to Silent Invasion: China’s Influence in Australia, a controversial jeremiad on Australia–China relations, author Clive Hamilton says he was affronted by the vociferous demonstration of Chinese patriotism in Canberra:

How dare they arrive, on the doorstep of our parliament, the symbol of our democracy, and shut down a legitimate protest, leaving me and a few hundred others feeling intimated for expressing our opinion?

I shared Hamilton’s sense of NIMBY umbrage. Indeed, in the lead-up to 24 April, I did what I could to prepare authorities in Canberra for the onslaught of Chinese patriots. Along with the Xi Jinping speech, I had also been given a copy of the secret document issued by the Chinese authorities to organise a supposedly spontaneous demonstration of patriotic solidarity in Canberra. I passed on a translation of the document with my own notes on the event to government contacts. I also expressed a view that similar patriotic activities would be launched on Australian soil in the future.

I had been aware of Chinese “united front” efforts involving patriotic young Chinese-Australians from when I was a student in the 1970s; I had also written about the rise of virulent state-sponsored nationalism in China from the 1990s.

A book like Silent Invasion has been a long time coming; unfortunately, it happens to be this book. Given the prominence of the People’s Republic of China in Australian public and economic life, it is indeed important that concerned citizens acquaint themselves with the underpinnings of China’s one-party state and its international behaviour.

Useful scholarship is available on how the Communists see the world and, in recent years, are pursuing a well-articulated strategy of global prominence. In the media and popular literature, however, just what that means for Australia is a subject that urgently requires articulate, well-reasoned, and balanced discussion.

Hamilton brings to the task a burning sense of urgency and a commendable passion; however, these same qualities too often occlude the very message that he is hoping to convey.

In the early 1940s, during China’s war with Japan, the Communist Party joined a coalition of forces opposed to the invaders. In tandem with the war effort led by the Nationalist government in Chongqing, the Communists pursued a clandestine strategy to build support for their long-term goal of ruling China. Their broad-based “united front” embraced anyone who might prove useful in achieving dominance, Chinese or foreign.

Silent Invasion attempts to identify the strategy and tactics of China’s long-standing united front work in Australia today. In so doing, Hamilton offers many details and insights of pressing relevance to the national debate.

Unfortunately, the books reads like a hurried draft report from the front line of opposition. In pressing home the point about clandestine Chinese activities, however, Silent Invasion too often makes its case by disparaging the majority of people who have dealings with China.

As a result, instead of alerting readers to the increasing challenges of dealing with Xi Jinping’s one-leader, one-party state, and in the process generating a sense of common concern, the author may instead too readily spark discord, sow the seeds of suspicion, and feed ingrained paranoia.

If there is to be an intelligent engagement with the issues raised in this book, I would suggest that a united front of a different kind is required: a broad-based and free association of lawmakers and members of the judiciary, public servants, journalists, public intellectuals, academics, business people, and concerned citizens.

Warnings about what is dubbed China’s “sharp power” – that is, an evolving global influence supported by invasive tactics – are being sounded elsewhere, and in more measured terms.

I would suggest that the heady message of Silent Invasion can be ameliorated by reading two key works that proceeded it: Anne-Marie Brady’s Magic Weapons: China’s Political Influence Activities under Xi Jinping, published in 2017, and Authoritarian Advance: Responding to China’s Growing Political Influence in Europe, by Thorsten Benner, Jan Gaspers, Mareike Ohlberg, Lucrezia Poggetti, and Kristin Shi-Kupfer, published in February.