“Orwell's goal was not good writing, Orwell's goal was to prevent people from lying.”

In an essay in 1945, George Orwell discussed the relationship between military innovation and the world order. The democratisation of small arms, he argued, gave a chance to anti-colonial independence movements. But the atom bomb, available only to powerful states, would make those states “unconquerable” and lock in totalitarianism. As other major powers acquired the bomb, a world order would emerge composed of rival unconquerable states. For this scenario he coined the term “cold war”, which he labelled a “peace that is no peace”.

An alternative dystopia, Orwell acknowledged, would be the fragmentation and “barbarism” of a world in which a weapon like the atom bomb were cheaply and easily replicated. But non-state terrorists have shown a relative lack of creative innovation, the 9/11 operation notwithstanding. Orwell’s prediction of a cold war was right, and inspired the hellscape of competing superstates – Eurasia, Oceania, and Eastasia – that is the backdrop to 1984.

Decades before improvement in AI leads to an anticipated “intelligence explosion”, we will likely see a kind of “unintelligence explosion” – a proliferation of AI-generated disinformation.

If we are now sliding into a second Cold War, as some have argued, the analogue to nuclear energy is artificial intelligence, or AI. This time, the most important technology race is not in the realm of atoms, but in the world of bits.

China leads the race in some AI sectors (facial recognition), and the US in many others, including top-tier research. One particular area of US advantage appears to be natural language processing (NLP), which resides at the intersection of AI-based machine learning and human speech.

The state of the art can be seen in the beta release of a text generator called GPT-3, developed by the non-profit research organisation OpenAI. It can code basic software, draft technical essays and, when primed with simple instructions, produce creative literature.

In fact, GPT-3 wrote the epigraph to this article, via the Thoughts interface built by Sushant Kumar. It created an original sentence about the philosophical aim of George Orwell generated by tagging one word to the end of the URL: “Orwell”.

Mind-blowing AI-generated tweets

— Sushant Kumar (@sushant_kumar) July 15, 2020

With @OpenAI's GPT-3 model (thanks to @gdb), I built an app that generates its own tweet given any word.

Also, these AI tweets are indistinguishable from human tweets.

Try for yourself (replace 'word' below with yours):https://t.co/LZN7RkTbE1

The model was trained on text from across the internet prior to October 2019 – pre–coronavirus pandemic – but its powers of extrapolation are such that it can create meaningful novel sentences such as this: “Don’t be ignorant about coronavirus. It’s easy to suppress, but hard to eradicate without knowing when you don’t have it.”

GPT-3 has many limitations. One leading AI researcher describes it as a “very intelligent idiot”. It has no understanding of what it is saying and no theory of the physical world. But the reactions of a number of programmers on Twitter who have access to the GPT-3 API suggest it has the power to elicit the slight shock of recognition that foreshadows our species’ encounter with an alien general intelligence.

We assume that most things we read are written by humans – for now. But GPT-3 changes the way you read. Midway through any article, I can now find myself wondering how to prove that the text is by a human. What are the signs of synthetic language? Is the grammar too perfect or the expression too lucid? Are there telltale phrases – call them “colourless green ideas” – that are highly original but somehow lack semantic depth?

We need to mitigate not just the long-term risk of superintelligent machines, but also the near-term risk of conflict between nuclear powers inflamed by AI-generated disinformation.

Decades before recursive self-improvement in AI leads to an anticipated “intelligence explosion”, we will likely see a kind of “unintelligence explosion” – a proliferation of AI-generated disinformation. Deployed by a state, AI tools have the potential to produce disinformation on a scale to overwhelm communication networks. In effect, AI-driven disinformation would be a denial-of-service (DoS) attack against our ability to make sense of the world. Colourless green content could become endemic in the information environment.

To ensure AI develops safely, we need to mitigate not just the long-term risk of superintelligent machines, but also the near-term risk of conflict between nuclear powers inflamed by AI-generated disinformation. Natural language processing is just one of an array of rapidly advancing technologies – from deepfake imagery to automated bots – that are changing the disinformation game. Government-run Twitter bot networks and cliques of fake journalists with AI-generated profile photographs are foretastes of this future.

Ironically, in a moment of geopolitical crisis, the internet, which originated out of a US defence program to deter nuclear war, might be turned against us.

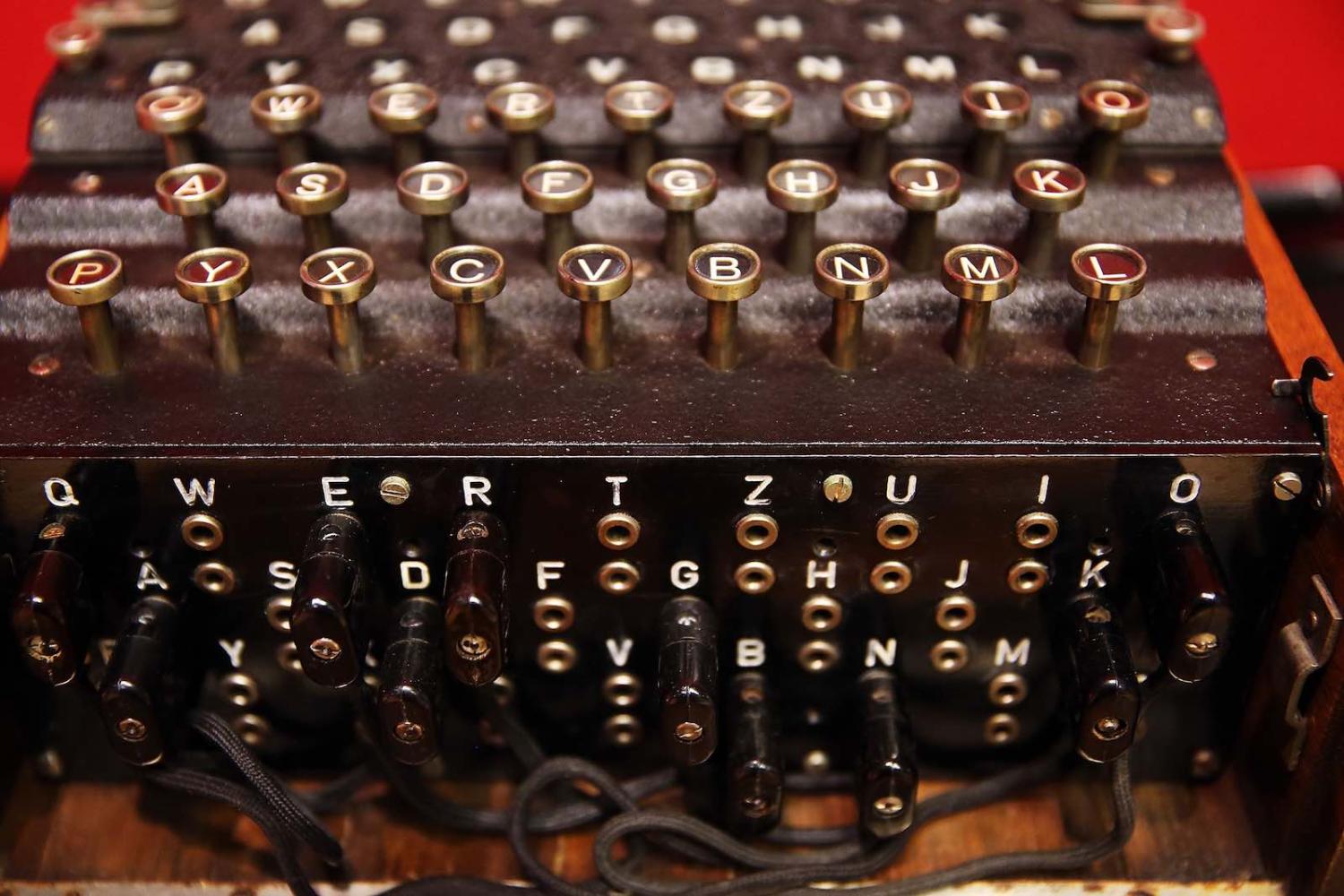

Alan Turing’s famous “imitation game” to answer the question “Can machines think?” continues to be an influential model for how to measure artificial intelligence. But the Turing test, by requiring a machine to successfully impersonate a human, is also a test of AI disinformation. When it comes to AI safety and existential risk, policymakers should prioritise not just the core problems of machine “control” and decision “explainability”, but also the urgent human problems of identification and verification.

Humans may sometimes have good reasons to be pseudonymous online. As an international norm, however, intelligent agents should be required to self-identify.