China’s President Xi Jinping’s concept of “common prosperity” is slowly being internationalised. The most obvious manifestation of this came last month when Xi framed the Belt and Road (BRI) as a vehicle for achieving global common prosperity.

While it is far from clear at this stage how common prosperity will impact China – yet alone its overseas investments – it is nonetheless possible to make a few tentative predictions.

First, a (rough) working definition. In October, the Chinese Communist Party’s theoretical journal, Qiushi, featured an article written by Xi outlining his common prosperity vision. Adam Ni, who translated the Qiushi article, describes common prosperity as “an overarching program that aims to promote socioeconomic equality while reinforcing party legitimacy and control”. Some of the key elements of this all-encompassing reform program include: reducing income inequality and boosting household consumption, improving “human capital”, promoting “tertiary distribution” and growing the “real economy”.

Chinese firms have long sought to portray all sorts of projects – some of which are actually almost entirely domestically focused – as being part of the BRI. This has been both to win subsidies and to curry favour with provincial governments and Beijing.

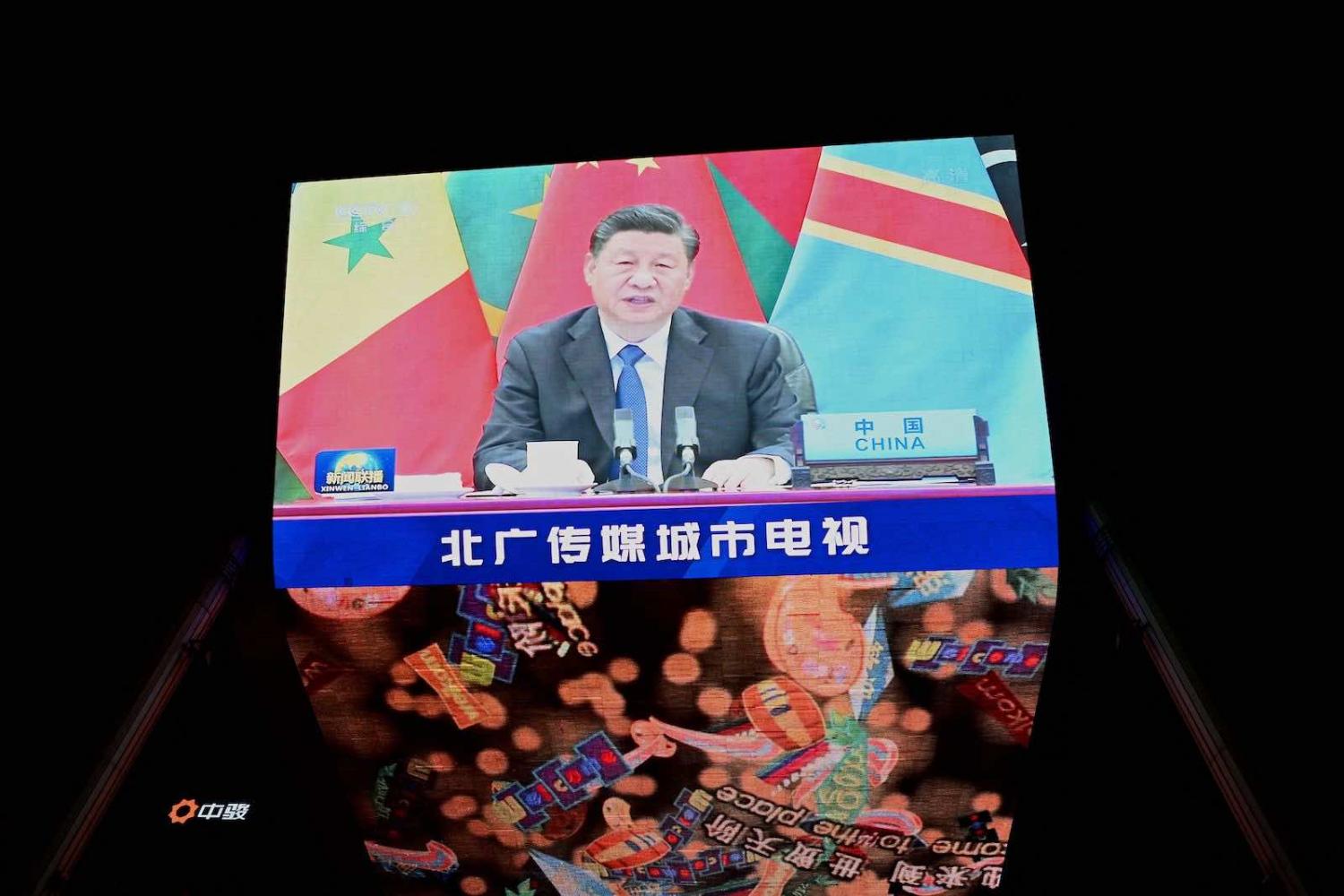

In a similar vein, Chinese firms operating abroad may seek to fuse – both rhetorically and in practice – BRI projects with common prosperity goals such as poverty reduction and human capital development. Neither would be a complete stretch. Speaking via video-link at the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation on 29 November, for example, Xi pledged to “undertake 10 poverty reduction and agricultural projects” throughout Africa.

The BRI’s main economic divers have been to provide outlets for domestic overcapacity and to facilitate market access for Chinese goods.

Although the BRI has been criticised for prioritising Chinese labour at the expense of locals, the picture is not uniform. In Central Asia for example, as Chinese firms have turned away from infrastructure and hydrocarbons towards manufacturing, there has been a notable increase in Chinese firms training local workers. Beijing and the Tianjin local government are also in the early stages of rolling out an overseas network of vocational colleges or “Luban Workshops”.

Xi’s emphasis on the “real-economy” could also engender a qualitative shift in the types of investments made along the BRI. Rather than technology platforms (think online gaming) and debt-fuelled property and infrastructure investment, in official parlance, the real economy refers to sectors such as consumer services, green development and higher value-added manufacturing.

Xi’s pledge in September to ban new coal-fired plants overseas could be a sign of an emerging trend. Energy is the largest sectoral segment of the BRI and China is well positioned to help fund the global energy transition. Unsurprisingly, English-language CCP literature has already linked renewables projects and “common prosperity”.

To the extent that these qualitative changes – which imply a more environmental, social and corporate governance friendly focus – do indeed materialise, they could provide a soft power boost for Beijing. A range of politicians and diplomats from countries including Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia, Pakistan and Malaysia have been quick to extol the virtues of common prosperity. Whatever the individual political motives of these officials, it is easy to see how common prosperity, at least theoretically, is a far more relatable concept for overseas audiences than Xi’s arcane “community of common destiny”.

All this being said, the BRI’s main economic divers have been to provide outlets for domestic overcapacity and to facilitate market access for Chinese goods, as well as to secure energy, raw materials and foodstuffs that cannot be procured in China. Common prosperity will interact dynamically with these driving forces (i.e., securing access to steel inputs and coal will gradually become less important), but is unlikely to override them.

In fact, with property and associated industries amounting to up to 30 per cent of China’s GDP, in the short-term, the BRI may provide an escape hatch for significant overcapacity in a sector that is struggling due to reforms made in the name of common prosperity. Nor is common prosperity likely to prevent “underhanded dealings between power and money” (which Xi railed against in his mid-August speech) that have sometimes characterised Chinese business practices along the BRI.

In a quantitative sense, that such high-level emphasis is being placed on what at its heart will likely be a domestic agenda may serve to constrain China’s overall stock of outbound investment. Instead of being encouraged to “go out”, Beijing’s corporate expectations appear to be shifting inwards.

This will manifest in several ways. Through so-called “tertiary distribution”, Beijing expects that companies will help develop human capital and reduce inequality within China. So far, this has taken the form of large donations – at least US$15 billion each in the case of Tencent and Alibaba.

Vast sums will be required to achieve other “real economy” objectives such as the energy transition and Beijing’s highly ambitious advanced manufacturing and innovation goals. All of this will give would-be Chinese overseas investors an additional reason to think twice at a time when geopolitical headwinds, capital controls and concerns about debt (both within China and overseas) are already making for a leaner BRI.

Over the longer term, whether these mostly incremental changes will become more apparent will ultimately depend on how successful China is in transforming its industrial base and shifting wealth towards households. Truly executing this vision will require radical reforms with no shortage of politically-powerful losers.