The End of the Vasco da Gama Era is vintage Coral Bell: bold and trenchant, with plenty on which both academics and policymakers might chew. Criticising it – especially with the benefit of hindsight – seems churlish. But it is necessary, I think, because it promotes a deeply problematic idea that still lurks in Australian strategic thought: the notion that a ‘concert of powers’ is the best way to manage contemporary international relations.

In the essay, Bell argued that the relative decline of American power, Islamist jihadism, climate change, nuclear proliferation, the growing prosperity of the non-Western world, and the uncertainties inherent in the transition to a complex, multipolar society of states were together likely to undermine international order. Managing these challenges, she thought, was beyond the capabilities of the US alone and existing institutions of global governance. Instead, she suggested an updated version of the 19th century European Concert.

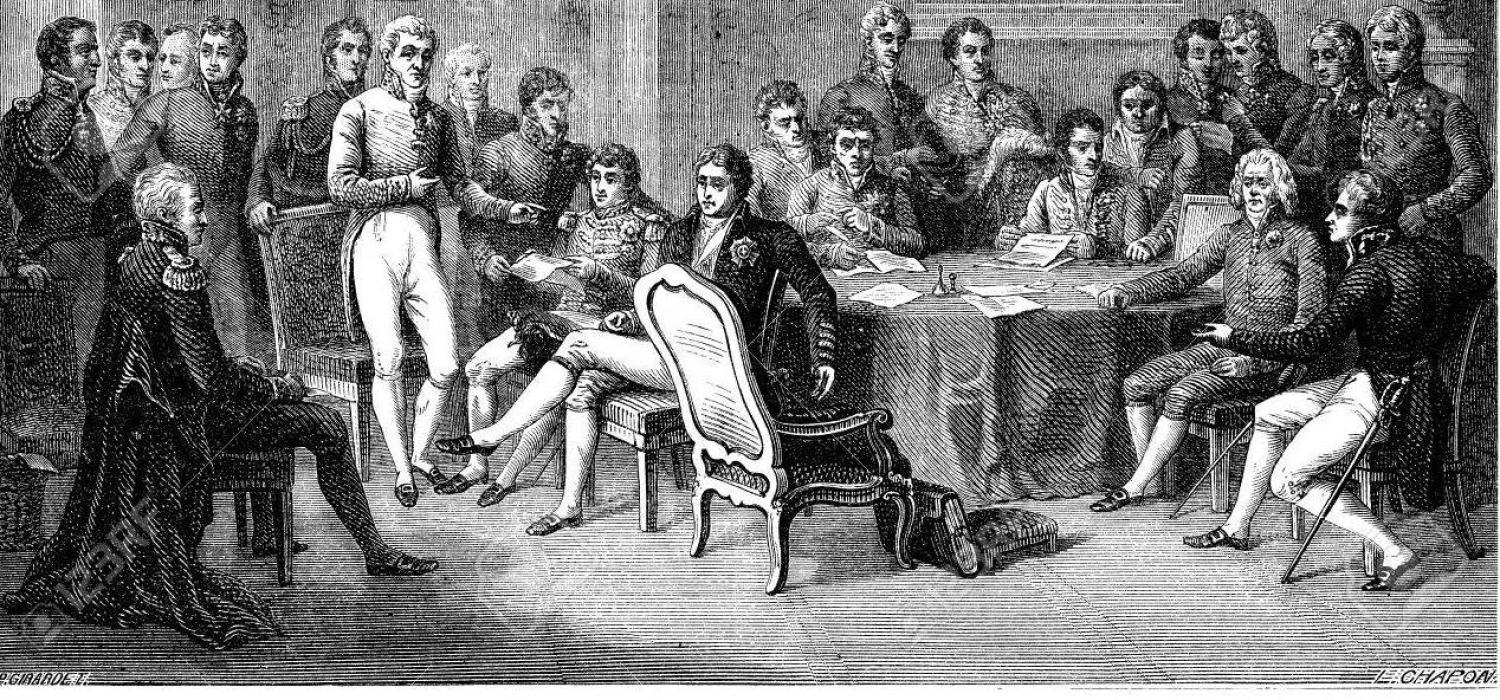

This idea had surfaced before in Bell’s work, in A World Out of Balance (2003), for example. Her interest in it was long-standing, a by-product of her fascination with Henry Kissinger, the subject of her The Diplomacy of Détente (1977). Bell’s concert of powers is very much Kissinger’s version, outlined in A World Restored (1957), his tale of how an enlightened few conjured continental peace and stability at a series of grand conferences held in the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars, balancing great-power interests with the needs of systemic stability.

In the 1950s, the concert appealed to Kissinger because it seemed to offer a way of managing the escalating tensions of the early Cold War preferable to those pursued by the Eisenhower Administration, but also because it affirmed his belief in the pivotal role of elite ‘statesmen’ in creating order out of chaos. Fifty years later, in different but no less challenging circumstances, it appealed to Bell for similar reasons, for she too was a ‘strategic elitist’, to use Robert Ayson’s apt term, convinced that great powers and great men make or break world politics.

Bell spent very little time in The End of the Vasco da Gama Era exploring the history of the European Concert. This, I think, was a mistake, because had she done so, she might have been less keen on the idea and what it might imply for a state such as Australia.

As Kissinger tacitly acknowledged by ending the story of A World Restored in 1822, the formal Concert of Europe was short-lived and its record more than mixed. It broke down as great-power perceptions diverged about which challenges to international order mattered most. Russia and Austria-Hungary, fearing their regimes might be overthrown, saw the rising tide of liberalism as the greatest threat; liberal Britain, wisely, demurred and withdrew into ‘splendid isolation’.

What was left of the concert system after 1822 did not prevent great-power wars, such as those fought by Russia and the Ottoman Empire (1828-29), Russia and a coalition of Britain, France, and the Ottomans (1853-56), Austria and Prussia (1866), France and Prussia (1870-71), Russia and the Ottomans (1877-78), and so on. To be sure, none of these conflicts escalated into general wars, but the great powers were busy using military force elsewhere – in expansionist frontier wars or in subjugating swathes of Africa and Asia, to devastating effect. The remnants of the Concert facilitated rather than curbed these bloody projects, with conference diplomacy used to divide the spoils, most notoriously in Berlin in 1885-86. And as Europe’s strategic elite enriched itself with extractive colonialism, other pressures grew unchecked by the Concert: nationalism and communism became more radical and militant, foreshadowing their roles in the disastrous wars of the twentieth century.

It is possible that a latter-day version, along the lines Bell suggested, would be an improvement on its precursor. But it is more likely that it would operate in similar ways, for similar reasons.

First, today’s great powers do not share perceptions of the gravity of the challenges of jihadism, climate change, and nuclear proliferation, still less how they might be managed. Great-power cooperation on these issues, whether bilateral or within the G7/8 and G20, has been patchy at best, suggesting that a modern concert could fall apart as quickly as its 19th century cousin.

Second, it is likely that the costs of concert bargaining would, as in the 19th century, fall on weaker states whose independence, territory, and resources would be traded away, ostensibly to keep the peace, but actually to satisfy the interests of the great powers and – importantly – their political elites. Such arrangements would not benefit relatively open, resource-rich, tricky-to-defend states such as Australia.

Third, a contemporary concert of powers would not address underlying issues that threaten medium- to long-term stability, not least populist discontent and the growing crisis of political legitimacy faced by domestic and international elites, be they democratic, authoritarian, or kleptocratic.