Coronavirus-related cyberattacks have proliferated since the first Covid-19 cases emerged in Wuhan, China. According to a recent Microsoft analysis, every country in the world has now experienced at least one such cyberattack, with the number of successful intrusions increasing daily. In a heightened state of confusion and stress, security gaps stemming from human vulnerabilities, such as email scams and unmonitored malware intrusions, have inevitably escalated.

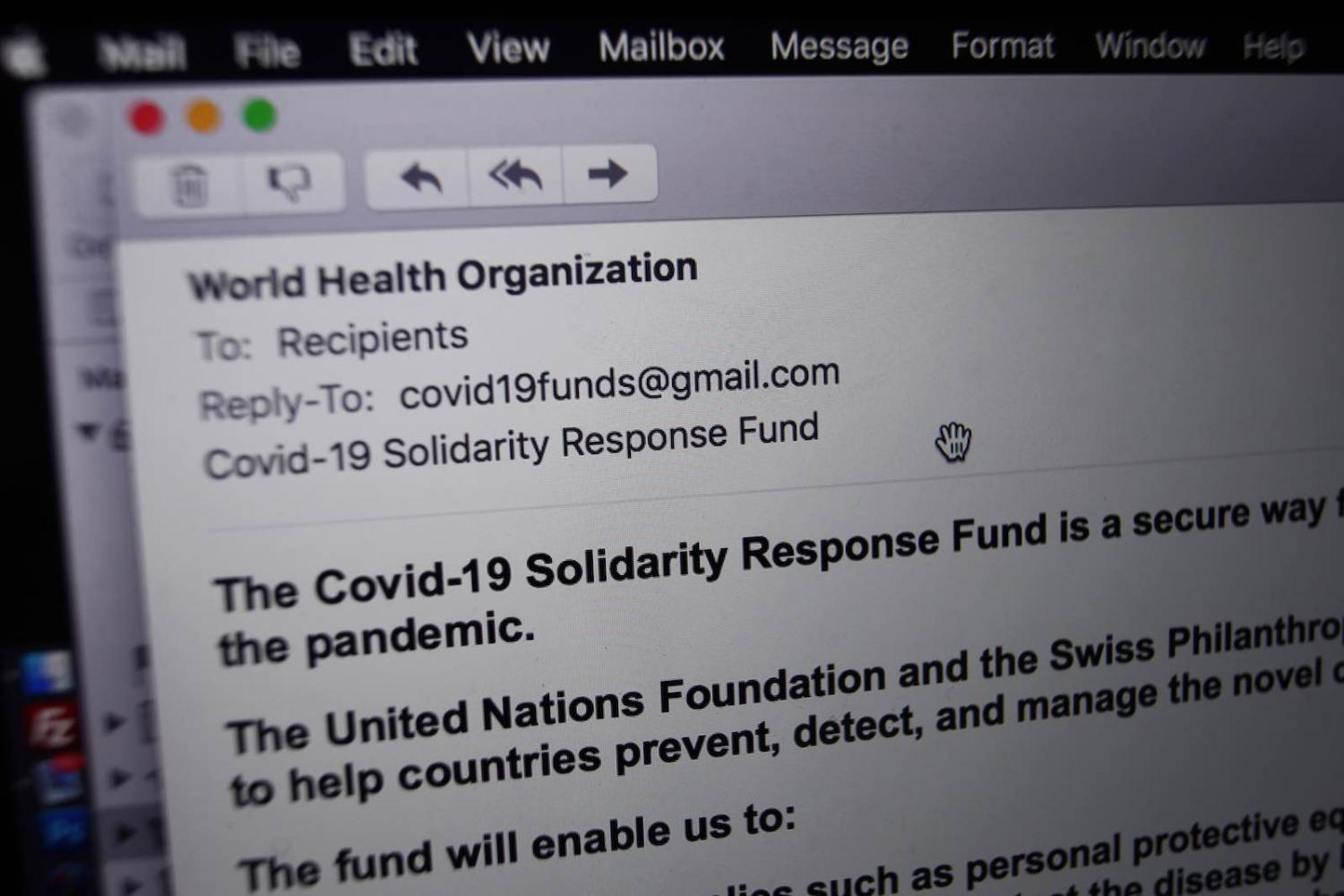

A variety of tactics and techniques have been observed. Attacks have ranged from unsolicited bulk spam emails aiming to spread disinformation or instigate scams, malicious domain names resembling legitimate sources, mobile apps that can be used for eavesdropping, or phishing attempts to steal private information. Sometimes, these techniques are used in conjunction with malware embedded within interactive Covid-19 maps, or ransomware that encrypts and prevents the use of a system until a payment is received.

While most coronavirus-related cyberattacks amount to mere annoyances, others have had serious consequences.

Such cyberattacks are not unique to this pandemic – capitalising on human vulnerabilities, particularly during major events, is a fundamental aspect of cyber threats. Malicious actors commonly use social engineering techniques to manipulate individuals to do something against their best interests. For example, phishing attacks have sought to take advantage of job duties (“Please read attached COVID-19 guidelines”), or even financial needs (“Click this link to view our FREE financial support guide”). Such vulnerabilities can also be exacerbated by a lack of adequate guidance from employers, especially at a time when oversight may be reduced due to staff and operational reductions, or during a rapid transition to remote working.

While most coronavirus-related cyberattacks amount to mere annoyances, others have had serious consequences. Essential services, including the healthcare sector, have become prime targets. The Brno University Hospital, a Covid-19 testing laboratory in the Czech Republic, was a victim of ransomware cyberattacks. In the US, multiple cyberattacks on pharmaceutical and medical research organisations compromised corporate networks through their supply chains.

Hackers have also quickly followed the shift towards remote technology, with multiple security flaws being exploited within remote-work application Zoom, creating surveillance and data privacy concerns. Amid the growing economic fallout from coronavirus, social security services have also been successfully hacked, such as those in Italy, illustrating the ability of malicous actors to rapidly adapt to the changing landscape.

While the motiviation is often criminal, sometimes, it can reflect geopolitical intent. Various state-sponsored “Advanced Persistent Threat” (APT) groups have been observed in attempts to exploit the pandemic to disrupt operations, steal intellectual property, and gather intelligence. Multiple phishing and spam cyberattacks against organisations in Ukraine, South Korea, and Vietnam were shown to have traces of state-sponsored APT groups from Russia, North Korea, and China respectively. Some APT groups have also sought to specifically target government services. For example, Vicious Panda, an allegedly Chinese-affiliated cyberespionage campaign by the Calypso Group, sent documents containing the RoyalRoad malware to individuals in the Mongolian public sector, masquarading as the Mongolian Ministry of Foreign Affairs disseminating information about Covid-19. Such malware would have allowed them to take screen shots, execute new processes, and collect system information as part of a suspected broader intelligence operation against a variety of other governments and organisations.

Several implications can be drawn from patterns in such cyberattacks. State-sponsored APT groups have predominantly focused on targeting organisations and governments in their regional spheres of influence, despite some having an international portfolio of operations. Essential services should expect to continue to be a target of coronavirus-related cyberattacks. Along with the healthcare scctor, financial services and industries that provide manufacturing, logistics, and cloud integration platforms could face an intensification of attacks on related supply chains as they become increasingly vital in a pandemic environment. This is especially worrisome considering cyberthreat reports before the pandemic had already pointed to the likely escalation of cyberattacks on similar sectors.

Furthermore, irrespective of any ethical boundaries which might be expected during a pandemic, hackers have had no compunction in flouting international cyber regulations, subsequently overwhelming enforcement capabilities. This amounts to a further warning with elections forthcoming in the US, Singapore, Hong Kong, and elsewhere of the lengths to which state-sponsored APT groups might use cyberattacks during major political events to influence and/or infiltrate foreign societies and governments.

It can also be expected that disinformation campaigns will intensify amid the current coronavirus-related “infodemic”. A recent Fireeye report found that many Covid-19–related themes aimed at Russian or Ukrainian audiences were in fact part of “Sekondary Infection,” a Russia-based disinformation operation. In some cases, efforts in manipulating social narratives are supported by cyberattacks, to reinforce political positions domestically and abroad – while others could also simply result from questionable decision-making, elevating unconfirmed rumours and circulating inaccurate information. Concurrently, by fostering chaos in social discourse, malicious actors capitalise on the environment of confusion, indirectly enhancing the effectiveness of cyberattacks while damaging mitigation efforts.

Effectively countering cyberattacks that leverage off similar major events requires preparedness and adaptability from the targeted organisation. It is crucial to understand that the primary vulnerability is people themselves, as gatekeepers to the security of any systems. The imperative for key decision makers is therefore to integrate the human aspect of cybersecurity into risk management frameworks, for the time of Covid-19, and beyond.