Whatever else the rapidly evolving and increasingly global health crisis may or may not do, it’s shining an unforgiving light on the relative capacities of national health systems. Even more importantly in the longer-term, perhaps, it’s providing a searching examination of political leaders, and the ability of very different political systems to deal with unexpected crises.

When the novel coronavirus Covid-19 first appeared in Wuhan there was a rather predictable pile on, as commentators from the US in particular pointed to the possible failings of the Chinese system. Too much secrecy, self-protection, and poor regulation of dodgy cultural practices were held up as examples of all that could go wrong in non-transparent authoritarian regimes governed by strongman leaders.

There was initially something to such criticisms, no doubt, as protecting the reputation and authority of Xi Jinping and the Chinese Communist Party seemed to take precedence over protecting the people. But once the scale of the problem became clear, China’s leaders moved rapidly to assert control and imposed draconian controls over the movement and behaviour of the population.

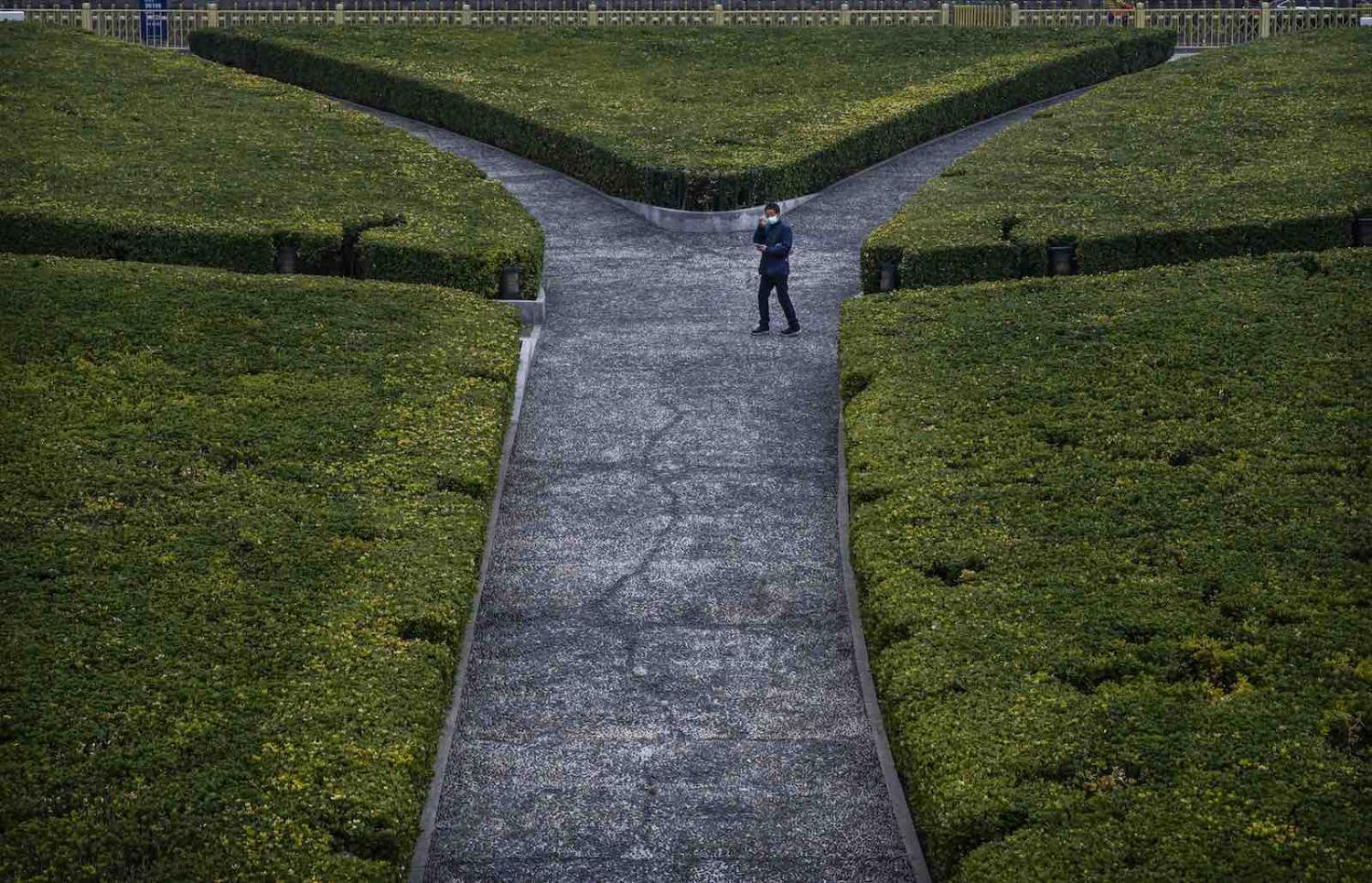

Whatever you may think of the CCP and the way it runs the country, it knows how to do social control. China’s population may not like it much – unless it’s happening in Xinxiang, of course – but they are used to living with authoritarianism, and are seemingly more willing to make the implicit trade-off between social order and social control.

Even those people who consider that an unacceptable bargain would have to concede that – when it comes to controlling pandemics, at least – it seems to be working. From being the epicentre of the global crisis, China has now become something of a role model for effective policy implementation, something confirmed by its rapidly falling infection rate. Certainly China also appears determined to shift the narrative in its favour.

In the United States, on the other hand, an altogether more chaotic story is emerging. Not only has Donald Trump admitted that he didn’t realise that flu of any sort actually killed people, but he has appointed his deputy, Mike Pence, to oversee America’s response. Pence has no medical qualifications, and his handling of a 2015 HIV outbreak in Indiana while he was governor of the state has come under renewed scrutiny. A former US Centers for Control director reportedly said of Pence that his inaction as governor gave Austin, Indiana, with a population of around 4200, a higher HIV prevalence than “any country in sub-Saharan Africa”. Yet Pence has now been put in charge of overseeing response to a public health crisis in a country of 327 million people.

Trump announced on Thursday a ban for non-essential travel to the US from Europe – exempting the United Kingdom.

Ironically, many of the working poor who propelled Trump into office do not have healthcare cover, have poorly paid jobs, and simply cannot afford to take time off work to “self-isolate”. The idea that a nation of supposedly rugged individualists would actually embrace such an infringement on their liberties is another question, of course.

More than half the American population is incapable of dealing with an unexpected $500 financial emergency. Health and human services secretary, Alex Azar told Congress that the government couldn’t control the price of test kits for Covid-19, something that may explain the fact that the US has performed five coronavirus tests per million people, compared with South Korea’s 3,692 tests per million.

It is not unreasonable to infer that true infection rates may be much higher than reported in the US, and that treatment will not be easy to access for the swelling ranks of impoverished Americans.

Crises proved an especially searching test for strongmen leaders who like to project an aura of competence if not invincibility. At least the infrastructure and capacity for such a response may be available in the US, if it can be mobilised and made available to those that need. The challenge is even more daunting in India.

India’s national health minister has announced a suite of measures to deal with the outbreak, including a ban on the export of pharmaceutical drugs and ingredients, screening international passengers, the formation of rapid response health teams, public awareness campaigns, the precautionary shutting of schools, and collaboration with private hospitals and laboratories. The government has also suspended most visas and visa-free travel until 15 April, and the national carrier Air India has cancelled flights to Korea and Italy.

However, health experts have raised concerns about the India’s ability to deal with a spreading epidemic, given the extremely uneven nature of its public healthcare system, its generally poor record of dealing with communicable diseases.

The first cases of Covid-19 in India were detected in the state of Kerala, where a well-functioning health system and responsive government has so far been able to detect, treat, and contain the virus. Other more populous states with dysfunctional healthcare systems, such as Uttar Pradesh, are unlikely to fare so well.

The Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh, Adityanath, a Hindu monk, claimed that overcoming mental stress by practicing yoga could prevent people contracting coronavirus. Adding to the growing sense of alarm is the spread of rumours and misinformation via social media, particularly Whatsapp and YouTube which are widely used in India.

Even in Australia, where expectations about competent and timely leadership are currently much lower, the corona crisis will provide yet another test for a government with a reputation for bungling and obfuscation. This really is an issue where the safety of the nation is at stake. One more stuff up could prove terminal, and not just for the government.