Once upon a time in a United Nations press office, in a country where the routine threat of violence made armchair pursuits something of a sport, a group of colleagues started a collection of all the bureaucratic jargon and mumbo-jumbo we encountered in our daily dealings with official information.

We called it “Words we hate”, and soon a formerly neglected whiteboard hanging on the wall became the locus of some of our most treasured work: skewering the airbags of meaningless pomposity and lifeless drivel we were professionally obliged to indulge.

Capacity building. Stakeholder engagement. Beneficiaries. “Much has been done, but much remains to be done” – when was that ever not true?

The list went on. Perhaps my favourite was, “The conditions were not right for conditionality” – just the sort of concoction that overflows with meaning to the initiated, while meaning precisely nothing to the rest of the world. A shibboleth for the technocratic in-crowd. The man who said those words is today the president of his country.

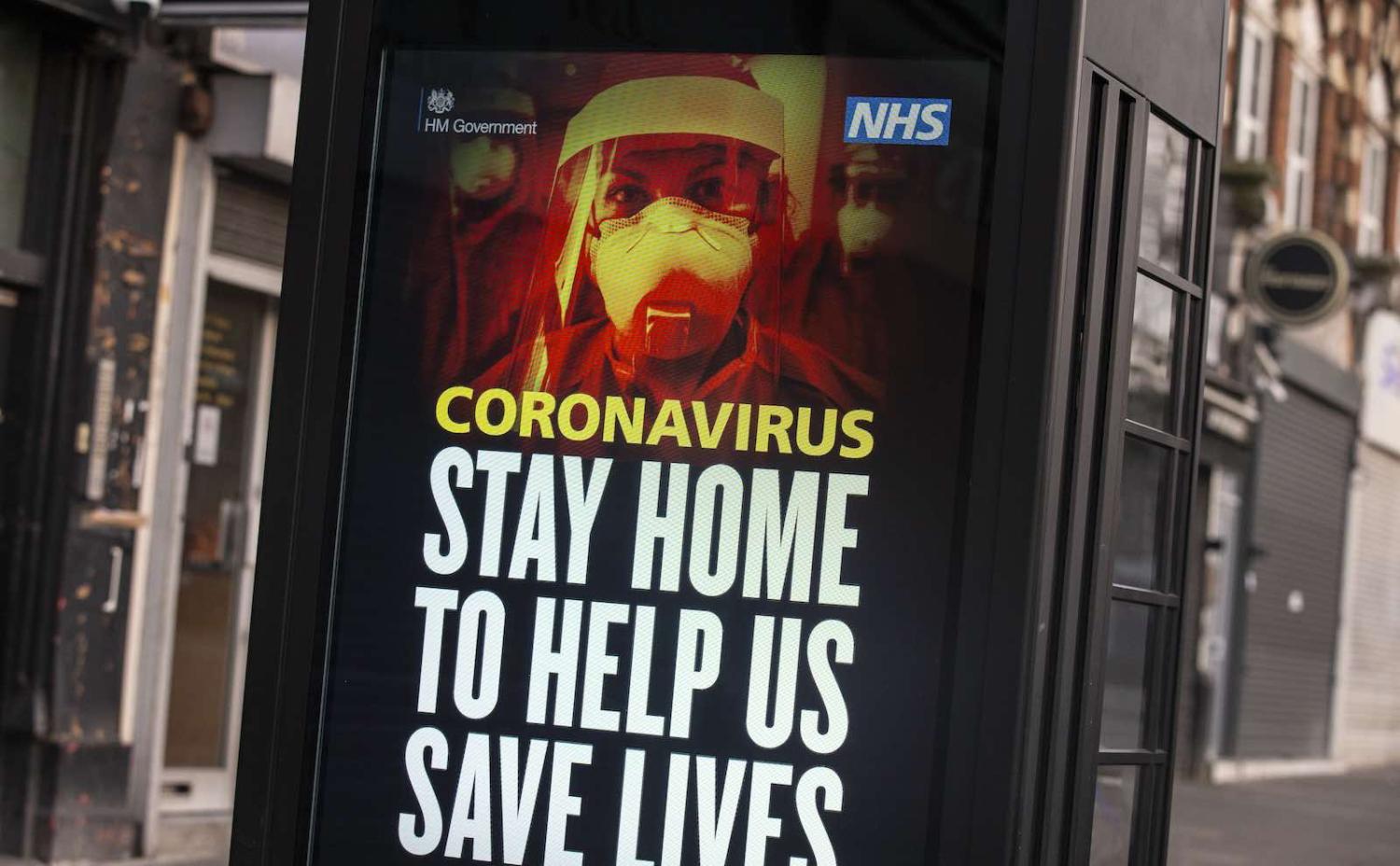

Despite the lies, the obfuscation, the blame-shifting, and the denial that have run rampant since Covid-19 came onto the radar, the only weapon of any use in this war is brutal honesty.

Now political leaders everywhere, at least those not selling miracles and macho fantasies, have no choice but to cut to the chase. The urgency and scale of the coronavirus pandemic make it murderous to condition public-health measures on political calculations and the conjuring of bureaucratic flimflam.

Bureaucratic machinery, of course, is adept at producing vocabulary that at first (and, for some, always) appears impressively profound and precise, but on close inspection reveals itself as bloated and evasive, sleight of hand to mask flesh and blood with tepid euphemism or academic chill – whether to spare the audience or the perpetrators themselves.

Inevitably at some point, a few of these laboratory-bred creatures make it into the wild, released in a controlled fashion through a carefully pitched statement, or escaping like prisoners from the mouth of an intemperate political functionary. The greatest hits become markers of an age, after the moment is gone and the argument has moved elsewhere.

The “known unknowns” of US Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld unveiled a square Pentagon thought matrix that would help catapult the US into the 2003 Iraq invasion with dubious claims of terrorist connections and weapons of mass destruction (WMDs, in the lingo of the day, naturally).

The “unknown unknowns” of that scenario turned out to be more than most of the cheerleaders apparently reckoned with. Who knew that an Iraqi journalist was going to risk his life to throw his shoes at the President of the United States? Or that suicide rates among US veterans would skyrocket, exceeding the number of American lives lost on the battlefields of Iraq and Afghanistan. Unknown unknowns, indeed.

PTSD became a household acronym in the US sometime in the 2000s, a clinical description of emotional pain and disconnect rendered in four letters of the alphabet. Suddenly everyone had this handy lingo in their kit, a way to make sense of the people who couldn’t make sense of their own experience, cast into the reality of war in a strange land and coming home to what used to be normal.

In a sense, it was progress. As a kid, I lived next door to a house that was mostly dark day and night, while the family inside cared for their grown son who had served in the Vietnam War. He had “shell shock”, which was all we were supposed to know. There is no cure for shell shock. PTSD is a step forward. There’s treatment.

Now, it seems, we are at war again. To go along with it, we’ve got a whole new vocabulary that would have made no sense to anyone just a few months ago. Except something is different. There are no bureaucratic euphemisms to soften the blow of death and destruction, no clever constructs to scrub the agency from acts of violence.

The Vietnam War gave use “collateral damage” and “hearts and minds”, neither of which described what they really meant. By the time of the 1991 Gulf War, the engineers had come up with “smart bombs”, which presumably only blew up the right people, so there was no more collateral damage. Now it’s known as “civilian casualties”, a good deal more honest, although surely there is nothing casual about getting killed in somebody else’s battle.

The so-called Global War on Terror that the US launched after 9/11 again gave people a new lexicon of insider expertise, even if going to war against a tactic seemed a bit confused. Asymmetrical warfare jumped out of the situation room and into bars and living rooms across America. There were “enemy combatants” subject to “enhanced interrogation”, bureaucratic terms of art meant not just to disguise the fact that prisoners of war were being tortured, but to declare, with a few imaginative strokes of legalese, that the Geneva Conventions – the laws of war devised to guard against such crimes – did not apply in this case, because everything was different. The rule of law, that thing that binds together the “international community” by shared agreement to a raft of conventions, has never quite recovered from the abuse.

Now everything really is different. The enemy is an unseeable organism which has found our greatest weakness in the need for human contact. The usual weapons of war are of no use in this one. The implements of the battlefield are face masks and test kits and ventilators. No one is going off to fight except for doctors and nurses and ambulance drivers, and the millions of workers whose everyday jobs now put them on the front lines. The rest of us can only jump into the foxholes of our own homes, if we’re lucky enough to have one, while peering out at the rest of the world through the periscope of the television, the radio, an internet connection. For the countless many who have no such privileges, the daily struggle to survive is now amplified by the fear that there is nowhere to hide.

No fancy terminology can shield us from this reality. Despite the lies, the obfuscation, the blame-shifting, and the denial that have run rampant since Covid-19 came onto the radar, the only weapon of any use in this war is brutal honesty. Wash your hands, self-isolate, flatten the curve. Testing, contact-tracing, quarantine. Those are the terms by which this time will be remembered. The difference is that they give people agency, rather than pulling the wool over their eyes. And they put science above sentiment. Bureaucratic BS is dead – collateral damage in the war against the coronavirus.

That might be something to celebrate, except by the time this war is over, we might all have PTSD from being locked down for so long.