A remote sandbank in the middle of the Indian Ocean, known as Blenheim Reef, is hitting the international news. The Mauritian government has sponsored an expedition to the reef to embarrass Britain in their long-running dispute over ownership of the Chagos Archipelago – which is home to the US military base at Diego Garcia.

But there’s a lot more to Blenheim Reef than meets the eye.

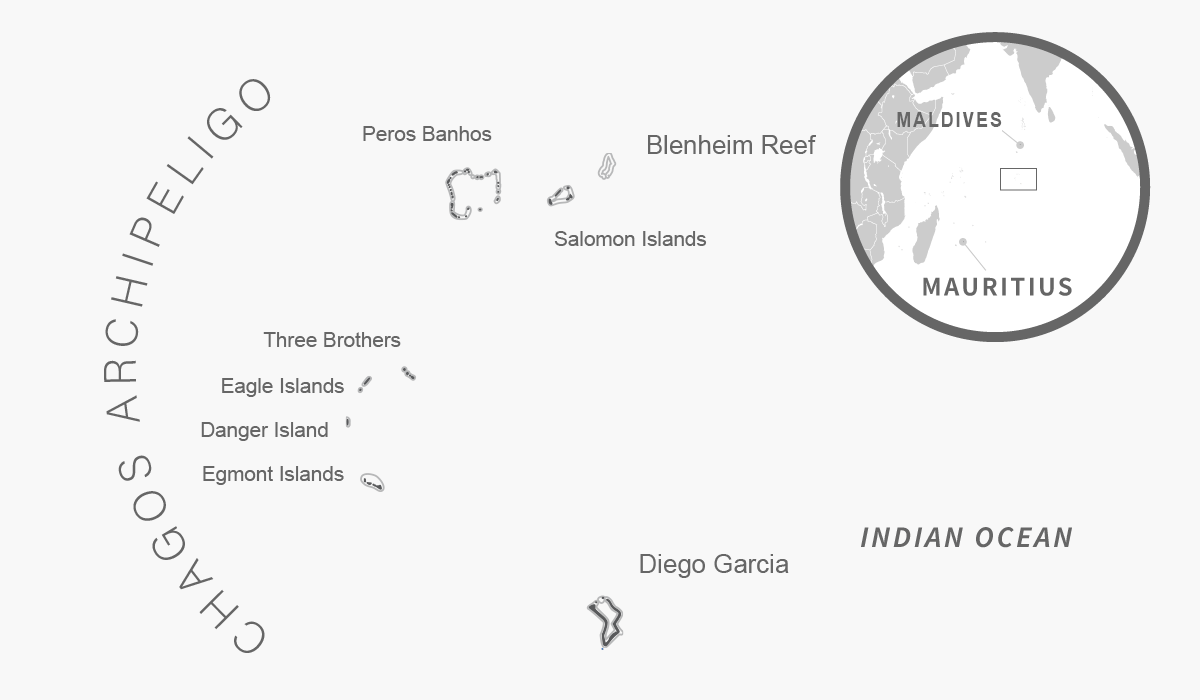

Blenheim Reef is a coral atoll located in one of the remotest places in the Indian Ocean, between the Chagos islands to the south and Maldives to the north. Although the ring-shaped atoll is almost 10 kilometres north to south and nearly five kilometres across, the sand and coral is only exposed at low tide and is covered in water at high tide.

As part of its ongoing attempts to regain administration of the Chagos Islands from Britain, the Mauritius government chartered a ship to visit Blenheim Reef after informing the British government (but not seeking their permission).

Although the expedition is officially conducting a “survey” of the reef, it is clear from the composition of expedition members (officials, lawyers, exiled Chagossians and journalists) that an underlying political purpose is to embarrass Britain.

What can the British government do in the glare of international media? Will this visit create a precedent for future unauthorised visits? The expedition seems to be a deft political move by Mauritius in further pressuring London over Chagos.

But the story is actually a lot more complicated than it initially appears.

In fact, it seems that Blenheim Reef may be terra nullius. Decades ago, the British government secretly concluded that the reef was not British territory and was owned by no-one, but declined to do anything about it.

The reef “is outside my jurisdiction”

According to now declassified Foreign Office files, the British government began puzzling over ownership of Blenheim as far back as 1975. Prompted by enquiries from an American visitor about ownership of the reef, Collin Allan, the Commissioner of British Indian Ocean Territory (effectively the civilian governor of the territory) concluded in a telegram to London that “the Reef is outside my jurisdiction.”

It seems that Blenheim Reef was not included in the 1814 Treaty of Paris that transferred Mauritius, Seychelles and their island dependencies (including Chagos islands) from France to Britain. Nor was it part of the 1965 Order in Council that detached the Chagos islands from Mauritius and established BIOT. It had been forgotten about.

The potential for another country to claim it – and, say, build an artificial island upon it – could have a major impact on the US base at Diego Garcia.

Allan proposed claiming the reef as British territory. He was concerned that someone might, in his words, “do a ‘Minerva’ on us” and declare the reef to be an independent country (as had been attempted at Minerva reef near Tonga in the early 1970s).

But as subsequent analysis by Foreign Office officials made clear, it’s not as simple as that.

The trouble is that, based on limited observations, the reef seems to be completely under water at high tide. This would make it a “low tide elevation” which as opposed to “rocks” and “islands” can’t generally be “appropriated” as national territory. Nor under United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea can low-tide elevations be used to generate territorial sea or an exclusive economic zone (as China has found out to its chagrin in the South China Sea).

Britain plants the flag

The Foreign Office decided to do nothing about these revelations.

But in 1982, officials were shocked to receive an overnight telegram from Navy Commander GN Wells, the senior British military representative in Diego Garcia. Wells told London that on 15 March 1982 he had landed on Blenheim Reef with a naval party “dressed in full white Naval Uniform” and planted a British flag on the sand (cemented into a 50 gallon oil drum so it wouldn’t float away).

According to the Wells telegram: “The British flag was raised over Blenheim Reef … and the territory formally claimed as part of the British Indian Ocean Territory.”

The Foreign Office was horrified – one official wrote the words “Good Grief” on the file. British Foreign Secretary, Lord Carrington, responded within hours with a cable stating that this action was not authorised, not to take any further action and to “suppress any publicity generated”.

In considering what to do about the situation, the Foreign Office bureaucrats were, in their own words, “nonplussed.” Wells’ action may have been unauthorised, but it was done with the best of intentions, and he was a senior British official in BIOT. Did it have any legal effect? According to their best advice, the reef wasn’t British territory and probably could never be, but they certainly didn’t want that publicised. On the other hand, taking the flag down would lose considerable face with the Americans.

One official concluded in an internal memorandum that it was best to do nothing, commenting that:

the flag be allowed to wither gently on its flagpole which it will no doubt do sooner rather than later, given the fact that it may well be under water some of the time.

“Terra nullius”?

But there were continuing fears that the Soviets or others may grab the reef. Indeed, during this time, there was a Soviet spy ship anchored at nearby Speakers Bank and there was concern that they may seek to establish a permanent presence. According to a memorandum from the Foreign Office legal advisor in April 1982:

Until sovereignty over it is asserted, it is terra nullius. In the absence of a claim to sovereignty by us it would be open to any other State to claim sovereignty over it.

Control over Blenheim Reef may matter even more today, for a lot of reasons.

Ongoing controversy over these and future visits to BIOT could be a major embarrassment for London, even if it is not technically claimed as British territory.

The potential for another country to claim it – and, say, build an artificial island upon it – could have a major impact on the US base at Diego Garcia.

Mauritius also wants to use Blenheim Reef as part of their assertions of a much extended exclusive economic zone in their maritime boundary dispute with neighbouring Maldives.

A lot depends on whether any features of Blenheim Reef (coral or sand) remain above water at high tide. Even if they did not several decades ago, they may now, as over time, coral atolls tend to grow into islands.

In coming days or weeks we may well see a Mauritian flag planted on Blenheim Reef, proclaiming it as Mauritius territory. How that would play out is anyone’s guess.

This article was produced as part of a multi-year project being undertaken on the Indian Ocean by the National Security College, Australian National University, with the support of the Department of Defence.