In Vladimir Putin’s Russia it is usually political moderates who are afflicted by sudden and extravagant illnesses, “accidents”, and assassinations. Whether the killing of dissidents such as human rights activist Anna Politkovskaya in 2006, the opposition politician Boris Nemtsov in 2015, or the poisoning of the anti-corruption figure Alexei Navalny with a fourth-generation chemical weapon, a steady parade of dead and incapacitated Russian liberals has usually signalled more of the same: tighter state controls, less tolerance of dissent, and more political repression.

What should we make, then, of the spectacularly violent car-bomb that killed Darya Dugina, daughter of the neofascist philosopher Aleksandr Dugin, and a budding ultranationalist in her own right? And was Dugin himself the real target, given that it was reported he changed cars at the last minute?

Was it a pretext for Putin to ramp up his war in Ukraine? His security services have blamed the hit on an alleged member of Ukraine’s infamous Azov Regiment. Within 36 hours Russia’s security services the FSB had concocted a fantastical tale involving a long stakeout, an ID card that was almost certainly faked, and a cunning escape by the alleged killer to Estonia – with her young daughter (and, apparently, her cat) in tow.

Or was the FSB itself behind the killing? If so, which FSB was responsible? Could it have been a rogue anti-Putin faction trying to stir up trouble for him? Or a pro-Putin faction seeking to give the Russian President a way to keep ultranationalists in line, or boost support for his undeclared wars against Ukraine and the West?

Was the killing linked to organised crime? Alternatively, did the fact that a previously unknown terrorist organisation (the National Republican Army) claimed responsibility signal a new internal struggle against Russia’s leader himself?

The truth is that we are unlikely to definitively discover who really killed Darya Dugina. The FSB’s allegations have been widely rejected, including by the Estonian Foreign Minister Urmas Reinsalu, who dismissed claims his nation was involved as a Russian “provocation”. Few experts believe that the “National Republican Army” was to blame, or that it would have much ability to enact terror campaigns linked to its apparently anti-Putin agenda.

And the FSB is, naturally, sticking to its story.

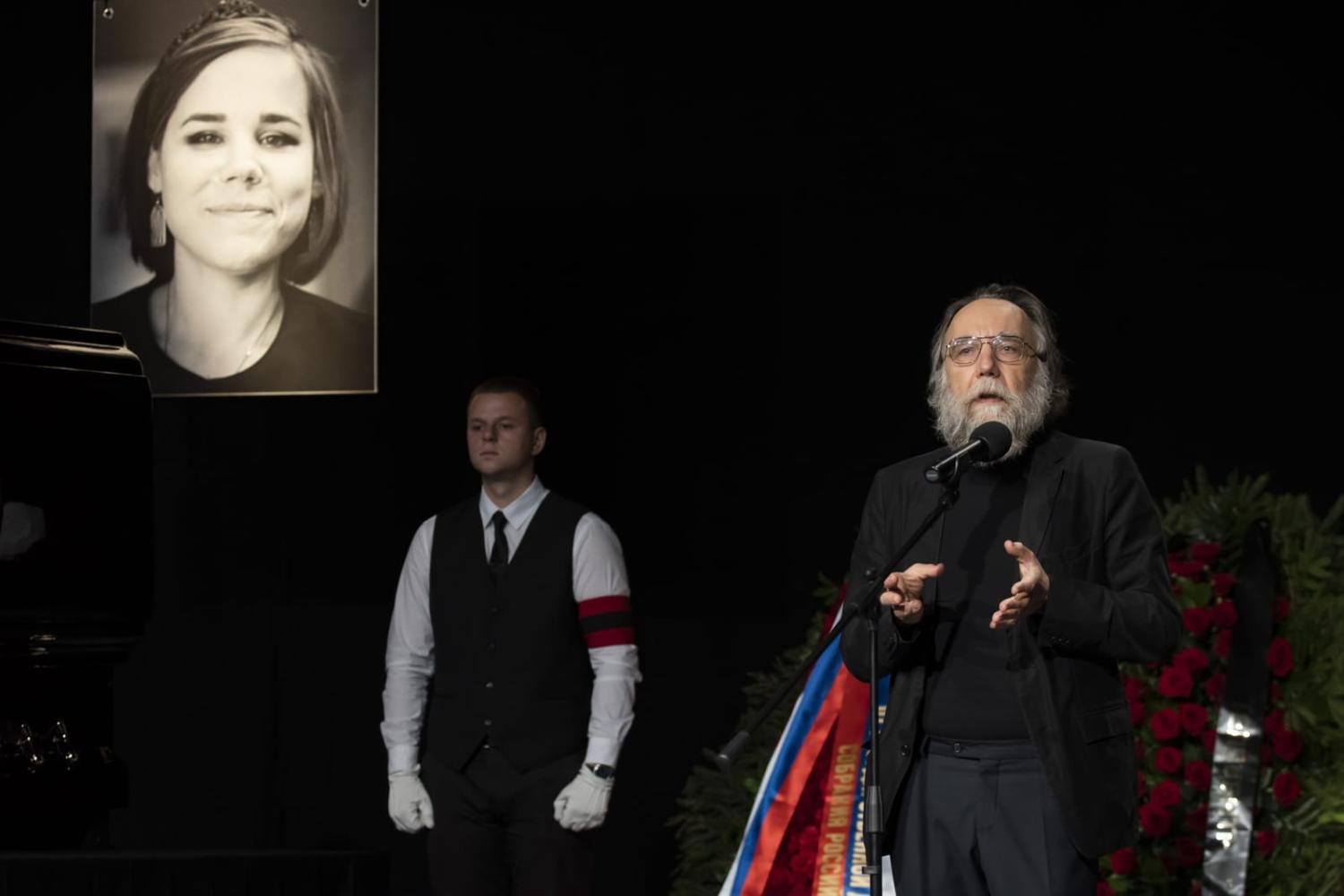

For his part, Dugina’s father Aleksandr claimed following her death that the “front line” had moved to Russia proper. A familiar line-up of Russian nationalists attended her funeral: from Konstantin Malofeev, the founder of the pro-monarchist Tsargrad TV channel where both Dugins worked; to Leonid Slutsky, the leader of the ultraconservative Liberal Democratic Party of Russia; and “Putin’s chef” Yevgenyi Prigozhin, the founder of the Wagner PMC group and head of Russia’s “Project Lakhta”, for whom Darya Dugina served as chief editor of the propaganda channel United World International.

And although Putin himself did not comment publicly on the killing, the Kremlin released a statement of condolences, and posthumously awarded Dugina the Order of Courage.

Dugina’s killing has certainly whipped Russia’s ultraconservatives into a frenzy. On Russian social media channels Dugina is labelled a martyr, amid calls for Russian “professionals who want to admire the spires in the vicinity of Tallinn” – a thinly-veiled reference to the 2018 poisoning of Sergei and Yulia Skripal with the chemical weapon Novichok in Salisbury, likely by the Russian GRU’s Unit 29155. Denis Pushilin, the Moscow-backed separatist leader, branded the Ukrainian government “terrorists” that had “tried to liquidate Aleksandr Dugin but blew up his daughter”. Sergei Mironov, leader of the Just Russia party, demanded Volodymyr Zelenskyy be deposed, a call repeated by Russia Today’s editor-in-chief Margarita Simonyan, who advocated strikes against Ukraine’s “decision-making centres”.

That said, it would be a mistake to argue that Dugin or his daughter are prominent members of the Kremlin elite close to Putin. Neither are household names in Russia, no matter how much Dugin liked to promote himself as “Putin’s Brain”, or his muse.

In reality, he and his daughter are probably better known in highly conservative Western online circles than in their homeland. As Gideon Rachman has pointed out, Dugin has ties to France’s National Rally, the Austrian Freedom Party and the Italian League. The US far-right figure Richard Spencer is also linked to Dugin: Spencer’s wife has translated Dugin’s works into English. When Dugin was interviewed by Alex Jones, he called for supporters of Donald Trump and Putin to unite against the “globalists”, itself a code word for New World Order conspiracy theorists, and often used to denote Jewish elites seeking to dismantle traditional Western societies.

While Putin briefly found Dugin useful, using him to stir up nationalistic fervour in his calls to “kill, kill, kill” Ukrainians in 2014, there is no evidence the two men have ever met. Indeed, Dugin has remained a largely marginal player from his early origins.

Following his expulsion in 1989 from Pamiat’ (Memory), an extremist organisation dedicated to the preservation of Russian culture, Dugin co-founded the neofascist Russian National Bolshevik Party alongside the avant-garde poet and author Eduard Limonov. Using Arktogaia, his own publishing house, Dugin launched his 1997 book Foundations of Geopolitics, which became especially influential in the Russian military. In it, he called for the unification of the Eurasian landmass under Russian leadership, which he saw as locked in a perennial struggle with the maritime United States and “its island ally, England”, requiring the creation of a friendly and stable Moscow-Berlin axis to combat it.

After briefly acting as an advisor to Gennady Seleznev, the Speaker of the Russian Parliament, Dugin founded “Eurasia” in 2001, a political movement that incorporated former military officers and members of Vympel, the special operations unit of the KGB. After being fired in 2014 for his views on Ukraine from the Faculty of Sociology at Moscow State University, Dugin became chief editor of Tsargrad TV. With Malofeev’s backing he also set up the think-tank Katehon, and the website geopolitika.ru: the former is an organisation promoting Dugin’s political philosophy and inspired by the writings of Carl Schmitt, while the latter advances his neo-Eurasian ideology and acts as a distribution channel for Russia’s information war against the West.

Dugin and his daughter are therefore best seen as amplifiers of Russian policy rather than direct influencers of it. But questions about their importance in Russian politics, whether the assassination of Darya Dugina was in fact intended to kill her father, or even who was responsible are ultimately less important than the effects of Dugina’s death.

And whereas the killing of a Russian ultranationalist potentially spells trouble for Putin, hinting at an increasingly complicated and fragmented struggle for influence in wartime Russia, the initial result has been to bolster the regime’s internal messaging that there should be no mercy for Russia’s enemies, either within or without. The LDPR’s Slutsky summed this up at Dugina’s funeral, with his post-eulogy cry of “One country! One President! One victory!” in a none-to-subtle echo of Nazi Germany’s “Ein Volk, Ein Reich, Ein Furhrer”.