Last month, a draft European Union Artificial Intelligence Act was agreed in the European Parliament. Arguably, the draft Act represents the most comprehensive and radical step towards regulating AI in the world. The final Act is expected to be passed later this year, with far-reaching consequences for international regulatory standards.

The Act comes at a time when key technological leaders in the development of AI are increasingly voicing their concerns about the dangers of AI for humanity. Indeed, there are many. After resigning from Google earlier this year, the “Godfather of AI”, Geoffrey Hinton, warned of the serious harms posed by the technology, and argued “I don’t think they should scale [AI] up more until they have understood whether they can control it”. OpenAI, the creator of ChatGPT, now markets its generative AI as “creating safe [Artificial General Intelligence] that benefits all of humanity”. Nevertheless, the company’s CEO, Sam Altman, recently called for greater government regulation of AI. In May, Altman warned a US Senate Committee that “if this technology goes wrong, it can go quite wrong...we want to be vocal about that”.

Certainly, there are enormous potential and realised benefits in using AI, especially in fields such as healthcare. Yet mathematicians, computer scientists and global tech giants who had previously been focused on those benefits – including mathematician Terence Tao, winner of the 2006 Fields Medal – are increasingly breaking the “taboo” and speaking out about their concerns for the technology’s harmful effects on humanity.

As Australia and other states consider closing the regulatory gap on AI and attempt to create the preconditions for safe, accountable and responsible AI, what can they learn from the draft EU AI Act?

Despite boasting the third-largest economy in the world, the European Union has placed human rights ahead of technological advantage. Among other measures, the draft EU AI Act aims to introduce three risk categories. First, where AI models are viewed as an unacceptable risk, they are banned. An example of this would be an AI-enabled system that the government of China has introduced to perform a type of social-credit or social-scoring regime. The EU AI Act seeks to prohibit authorities across the EU from introducing such social-scoring systems, as well as “real time” biometric identification systems in public spaces for the purposes of law enforcement.

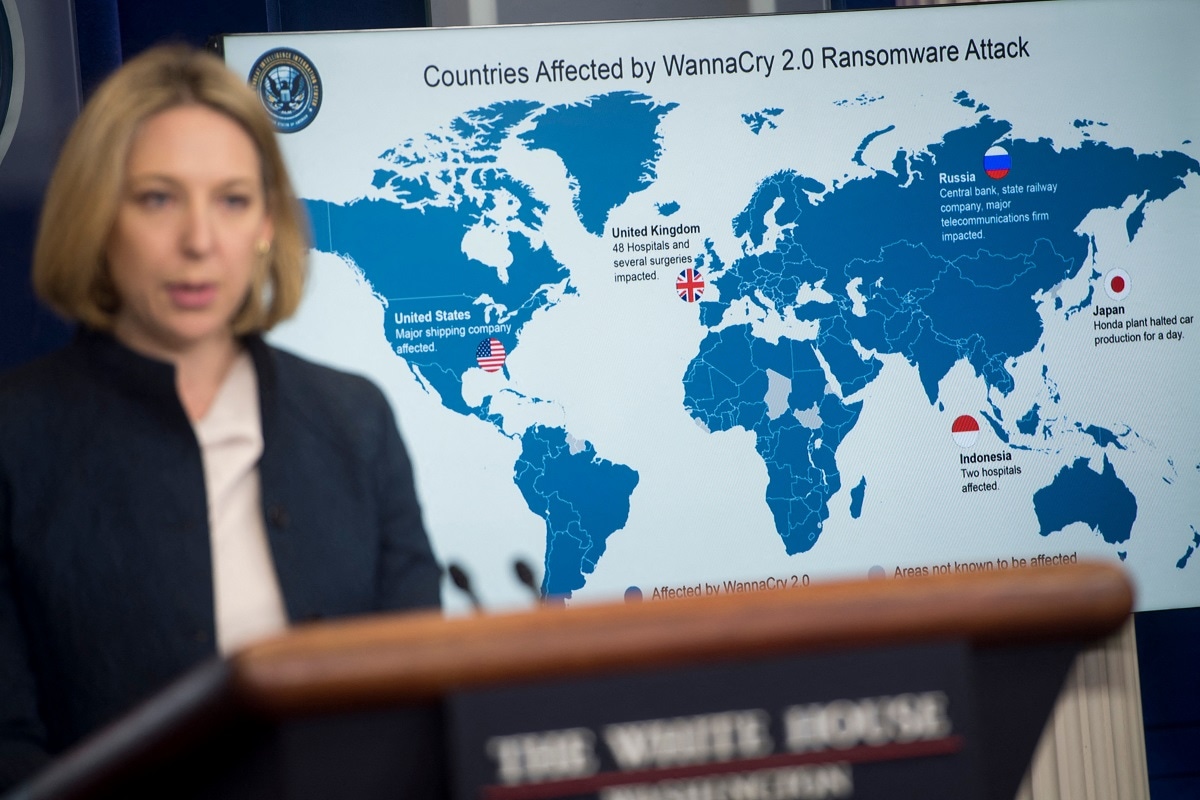

Australia and others could consider adopting a similar approach. This would not only ensure AI is aligned with Australia’s democratic and social values, but also establish that AI systems that perform social crediting are prohibited under Australian laws. It could also deter the malign use of AI, such as that described by legal academic Simon Chesterman as the “weaponisation of AI – understood narrowly as the development of lethal autonomous weapon systems lacking ‘meaningful human control’ and more broadly as the development of AI systems posing a real risk of being uncontrollable or uncontainable”.

Second, the draft Act would mean AI systems considered high risk applications would need to adhere to particular legal obligations. This necessarily requires that an AI model be developed in such a way that it can be explained, is transparent, fair and unbiased, and demonstrates standards of accountability in terms of training and operationalisation.

Third, those models considered not a risk or of minimal risk, which is the vast majority of AI systems, would remain without restriction. This category would include AI models used in computer games, for example.

Rather than limit innovation, this process of categorising the risk of AI systems through a legal standard would provide businesses and consumers with clear rules around what is considered trusted, accountable and responsible AI – particularly in a world that is becoming less trustful of the technology. A recent survey by the University of Queensland, entitled Trust in Artificial Intelligence: A Global Study 2023, found that 61 per cent of respondents were wary of AI, and 71 per cent believed AI regulation was required.

By no means is the draft EU AI Act a silver bullet. Yet it is a vital and significant first step to preventing the worst effects of AI on humanity and starts a necessary debate on how we would like to control its future.