The ongoing debate about whether ASEAN (still) matters, and how important it is for Australia, could not be more ASEAN in style.

Euan Graham and John Blaxland represent the two major camps: ASEAN-enthusiasts and ASEAN-sceptics. The truth is that they both are right.

ASEAN means different things to different stakeholders. It is an institution composed of very diverse members and has taken up a very wide-ranging agenda. The strategic value of the organisation for its individual members varies based on their differing geopolitical situations and political leadership at any given time.

For older and newer ASEAN members, another factor is their varying levels of socialisation within the institution. And with such an enormous agenda, it is little wonder that where one member sees relative successes, another sees inefficiencies.

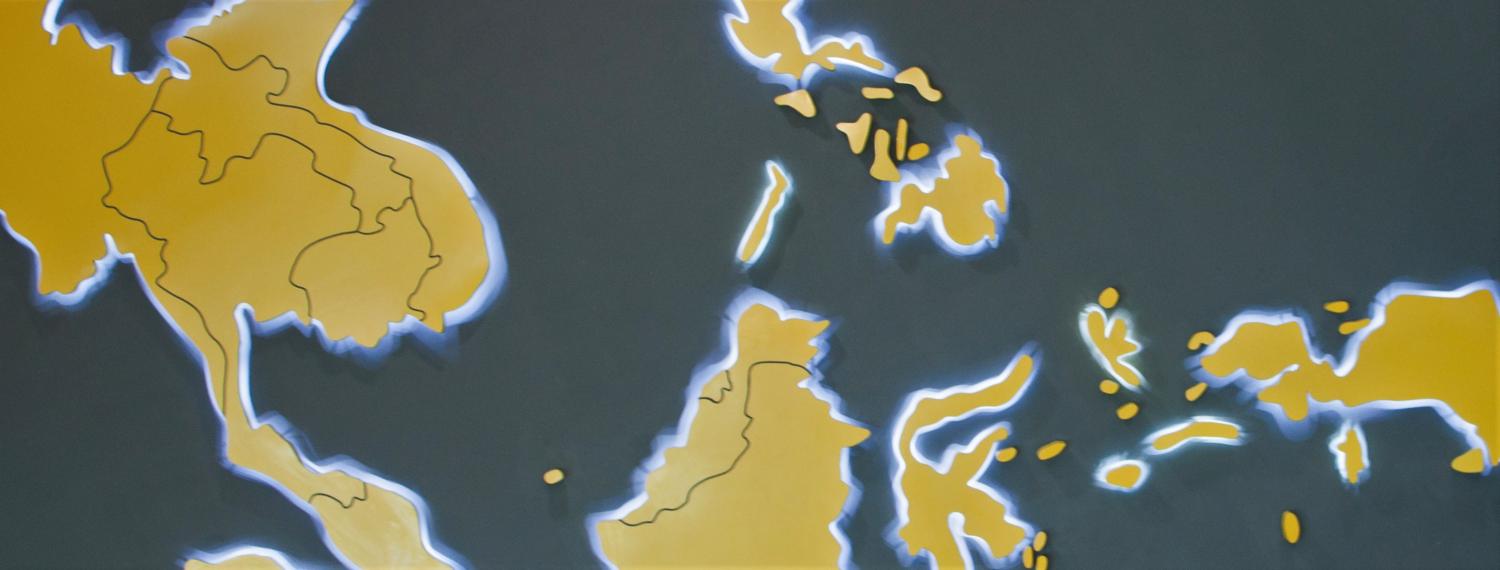

Regional disputes have been a high-profile litmus test for ASEAN’s effectiveness. The most prominent of these is the South China Sea, in which a number of ASEAN members, along with China and Taiwan, have overlapping claims. On this issue, ASEAN’s political efforts have been imperfect. Numerous regional forums have ended without reaching the (in)famous ASEAN consensus. It has been more than 25 years since the regional body began attempting to address the South China Sea issue; today, it may be getting closer to a joint agreement on only a Code of Conduct framework.

But the South China Sea is by no means the only dispute on ASEAN’s agenda. Transboundary haze or Rohingya refugees add to perceptions of a toothless ASEAN. Notions of reinventing the ASEAN Way, such as ideas for “ASEAN Minus”, are a sign of frustration over institutional imperfections.

On a number of other issues, however, there is more room for successful multilateral cooperation, with increasing consensus on matters such as counterterrorism and transnational crime.

Expectation versus projection

The question of expectation persists: should ASEAN address such major issues, and if so which ones? In 2015 Singaporean Ambassador-at-Large Bilahari Kausikan famously coined the metaphor of ASEAN as a cow, not a horse:

ASEAN is far from perfect. It certainly needs improvement and there are many areas where its workings can be improved. But a cow will never become a horse … we should consider how we can improve the bovine breed; how we can make a better cow, rather than scolding it for not being able to run as fast as a horse.

This boils down to the exact issue the body is facing, of expectations versus projection. But there is an inconsistency: while some want ASEAN to be assessed as an imperfect cow that does not aspire to be a horse, others desire glory and credit for the organisation. Communicating contradictory images and aspirations does not help create a consistent perception of ASEAN among its external partners. It is also not helpful for the following generations of ASEAN leaders, who will grow increasingly distant from its founding principles.

While debating ASEAN, it is important not to conflate it with South East Asia. John Blaxland is right to appreciate the importance of South East Asia not only as a region of high potential and growing importance, but also one susceptible to volatile changes.

While ASEAN is shaped by regional states, and vice versa, it does not equal South East Asia. ASEAN is an institution, and an institution is only as strong as its weakest link. It is assessed on its performance, not on how important its members are. Even with the ablest members, no organisation can excel without leadership and vision.

No doubt ASEAN matters – the EU aside, it is among the world’s most successful and long-lasting examples of regionalism. Yet complacency based on past glory is dangerous. What matters is how to keep ASEAN relevant 50 years on, and how to manage differences in perspective between its members.

What’s in it for Australia?

Amid geopolitical challenges to stability and some questioning of multilateralism’s virtues, collective efforts can be easy to dismiss. External influence can also diminish South East Asia’s regionalism.

But South East Asia is a region Canberra cannot afford to overlook. Australia has consistently supported South East Asian regional institutionalism, and should continue leveraging both bilateral engagements and multilateral frameworks. Canberra became ASEAN’s first dialogue partner in 1967, and has a longer institutional memory of the organisation than half of its members.

As a strong and consistent supporter of multilateralism, the rules-based order, and liberal institutions, Australia plays an important role in sustaining ASEAN’s institutional confidence and consolidating its sense of collectiveness. Such a role is particularly important in the wake of a power shift that has brought the role of international law in the global order into question. The Australia-ASEAN Special Summit serves as an excellent opportunity to reinforce that.