While nuclear-powered submarines steal much of the media limelight, the AUKUS security partnership between Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States is about much more than the submersible warships. And it is headed for a critical phase.

The partnership will include additional cooperation in defence-related science and technology, industrial production and supply chains, and cyber and AI capability. This will involve significant contributions from the private sector of each partner economy and require ongoing intellectual property (IP) transfers between partners. Such transfers and storage of highly sensitive data will require information security and network resilience. In the contemporary era of strategic competition between economically interdependent nations, IP theft poses unique challenges that AUKUS partners must overcome.

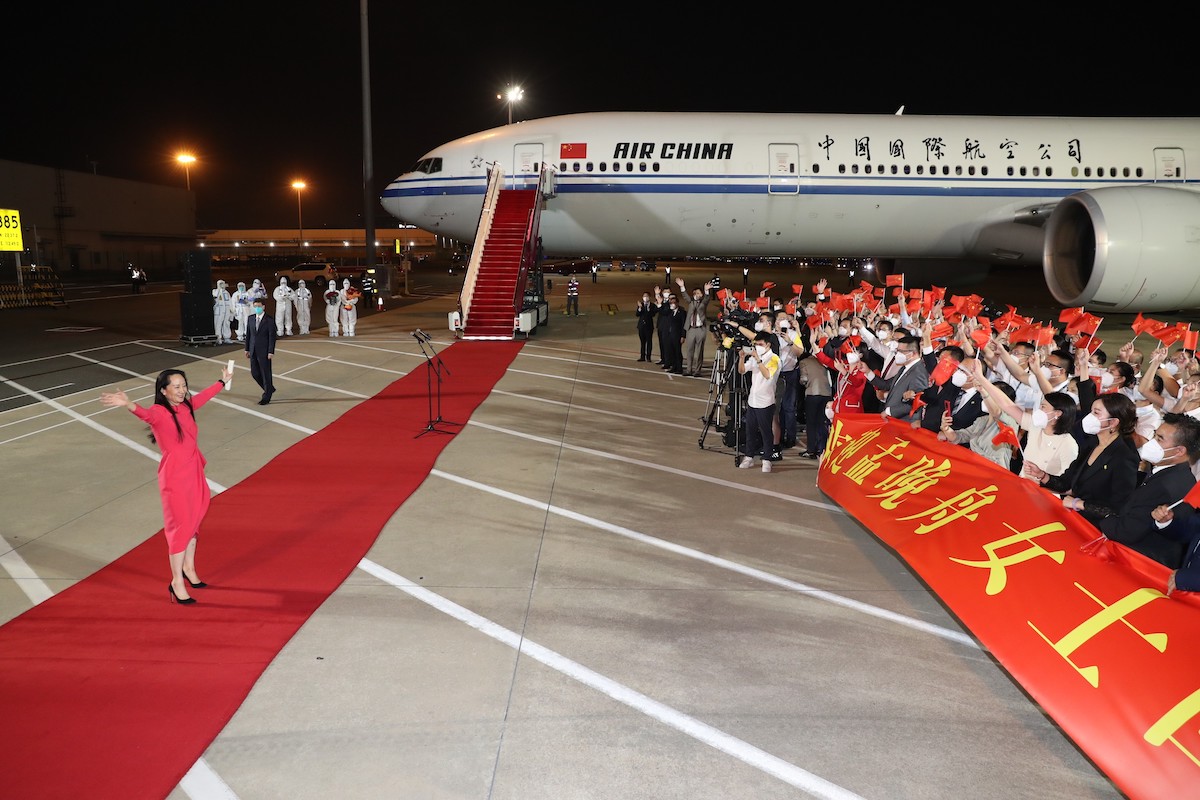

The economic cost of IP theft is difficult to calculate, with official US economic losses due to Chinese actions estimated at between US$225 billion and US$600 billion. Even the lower end of this estimate is vast. While there seems to be no comparable official estimate for Australia, there are high-profile examples of IP theft (here, here and here), as well as Australia serving as legal jurisdiction for the adjudication of an IP theft case involving Motorola and Chinese firm Hytera. The Chinese state is recognised by AUKUS governments as the single most active global actor in conducting and/or sponsoring malicious cyber operations with the aim of transforming stolen IP into defence capabilities and private sector products. It is well documented that China’s legal system actively enables IP theft, which is made possible by a politically dependent judicial system subject to Chinese Communist Party (CCP) directives.

Yet it may surprise some that another significant contributing factor to Chinese economic espionage is the unwillingness of victimised private businesses to take legal action against Chinese firms or the state. A recent investigation of IP theft in the world’s most targeted economy, the United States, found that it was “allowed to quietly continue because US companies had too much money at stake to make waves”. For example, in 2010, when Google revealed a major China hack, 33 other American businesses that were also hacked refused to make public statements.

One reason for their silence relates to the CCP’s willingness to use its vast domestic market access as both carrot and stick, punishing firms that make statements on issues the Party views as politically sensitive. Private businesses operating in China are therefore right to fear they will suffer potentially serious financial costs if they displease Beijing. Their ultimate concern is making profits for owners and shareholders, resulting in micro-motives that have the unintended effect of undermining national security imperatives around safeguarding IP. Wendy Cutler, an experienced negotiator at the Office of the US Trade Representative notes, “We are not as effective [combating IP theft] if we don't have the US business community supporting us”.

The issue of private firms wishing to remain anonymous when targeted by Chinese IP theft will become increasingly important for AUKUS members operating within the context of economically entangled strategic competition. At present, a key issue is the lack of a universal mandatory duty of corporations to report cyberattacks. A duty to report, enforced by financial penalties, would be a good initial step to improve corporate cyber governance. At present, only firms listed on the Australian stock exchange (ASX) are obliged to report a cyberattack.

Breach of disclosure obligations can lead to large financial penalties if discovered by the Australian Securities and Investment Commission (ASIC). The rationale is that such information could be crucial for assessing the market value of the targeted company. However, given that Australia’s defence economy relies mostly on small businesses across the country, notwithstanding a few large defence contractors, the limitation of relying on ASX disclosure rules becomes clear.

From an Australian perspective, Canberra should engage in policy-learning from Washington’s recent initiatives by following suit on two fronts. The first involves an Australian version of the US Commission on the Theft of American Intellectual Property. Others have already made convincing arguments for that institutional development, to which the authors of this article add their support. Such a commission is a much-needed step to fully understand the threat posed by IP theft to Australia. A second proposal is to create a parliamentary committee with a mandate similar to the recently established Select Committee on the Strategic Competition Between the United States and the Chinese Communist Party. The remit of this committee includes a focus on US corporate relationships with China, and how these impact issues of national security.

While the US example is mostly bi-partisan in nature and calls for the private sector to play its part in terms of awareness and alertness, one of Australia’s challenges is to establish a whole-of-government approach that allows for engagement between the business community, national security community and academia by way of co-opted membership of respective organisational bodies. This would allow better cross-understanding of each group’s risks and goals, as well as how these intersect dynamically.

“Australia is facing an unprecedented challenge from espionage and foreign interference”, the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation’s Director-General pointed out during last week’s presentation of ASIO’s fourth Annual Threat Assessment. And China is central to those challenges. As a result, the valuable economic gains Australia and China both harvest from their bilateral trade relationship should not be used to justify a policy of “softened” vigilance concerning China’s clear and present danger to the nation’s democracy and economy. AUKUS supply chains and private defence contractors across the partner economies are clearly in the firing line. It is the government’s job to reduce their exposure.