This post is part of a debate on Australia’s foreign policy White paper 2017. Click here for other debate posts.

The debate on Section 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act is of limited interest to most people, but nonetheless reflects a divide on values in Australia. This divide has profile, given the wash from Donald Trump’s accession to the presidency in America and a shift in political attitudes in Europe.

At one end of the values spectrum sit those for whom multiculturalism is not a descriptor, but an ethos. They are progressives on gender and sexual identity and are intolerant of those who are not. They can be too ready to regard other Australians as stupid.

At the other end are those who like flags. They prefer to keep foreigners out of Australia rather than to let them in. They are most comfortable with members of the so-called Anglosphere. The wealthy in this group want to stay that way. The poorer in the group believe that others are responsible for their poverty or dispossession.

These sets of values separate those who prefer the familiar to the foreign, the realistic to the idealistic, and beliefs based on history to outlooks premised on geography. Australians are not extremists. The values of most lie somewhere between the two poles.

Of one thing be sure, as Australia this year re-examines the shape of its foreign policy in a White Paper, there will be calls for it to reflect Australian values.

And so it should. The preservation of a nation’s values is a core interest for a democracy, along with security and prosperity. It has to be. Values derive from history, beliefs and systems of governance. They define and reflect the sort of people we are and what we want of our society.

That said, given different community perspectives, in a democracy values have to be mainstream to make sense as a basis for foreign policy. The perspectives of the poles are not mainstream. Mainstream values derive from a mix of generosity, fairness and tolerance on the one hand and competitiveness and self-interest on the other.

Values play a proportionately larger part in the conceptualisation and practice of Australian foreign policy than is the case in most other Western democracies. This is because our immediate neighbours, other than New Zealand, have different traditions and hence value structures. This puts us in a different position to, say, Canada or the Netherlands, whose primary relationships tend to be with countries whose values are not too different from their own.

How then do values work in foreign policy?

Over the longer term a democracy cannot conduct itself in a manner that is inconsistent with mainstream national values without suffering popular opprobrium. For example, when it engages militarily, a liberal democracy will be obliged to minimise harm to civilians. It will be under pressure to prevent its businesses from engaging in corrupt practices abroad.

A second concept, particularly for a middle power, is that adherence to international norms helps engender and preserve an environment in which raw power is regulated.

These norms are based on value structures to which we subscribe. If we don’t adhere to these rules, why should others? We bent the rules when we intervened in Iraq. And our unhappy management of the refugee issue has called into question our adherence to the spirit of the Refugee Convention. These actions were not unambiguous breaches of international law, but they impinge on our capacity to argue from the high ground when we criticise, for example, Chinese actions in the South China Sea.

A third issue is the degree to which we seek to impose our values on others. The history of Australia’s relations with Asian nations is replete with examples of our value- based actions impinging on our other dealings with those countries: human rights with Indonesia and China; governance with Thailand; media freedoms with Singapore and so on. Animal rights issues have been prominent in our dealings with both Japan (whales) and Indonesia (cattle). Alleged racism has also featured in our discourse with Asia (for example, with India).

Our approach on such questions is shaped by the principle noted above that a democracy has to reflect mainstream values. But there is in practice some room for flexibility on how we comment on the domestic policies of others. In the real world, our neighbours are not perfect. Nor are we. In the end this issue is one for careful judgment rather than a practitioner’s handbook.

The fourth question is how Australia should regard the juxtaposition of the United States and China in the region in a values context.

A foreign policy dichotomy is frequently presented for Australia between according overall priority to dealings with the United States on one hand and with Asia on the other. Of the Asian powers, Japan, South Korea, India and most in ASEAN want the US presence in the region to continue, not only to countervail China strategically but because they are more comfortable with US values (for all their imperfections). Hence ANZUS is a plus from their perspective.

The exception is of course China itself. China would prefer that we (as well as Japan and South Korea) had a different relationship with the United States. We have to deal with that. Some problems don’t go away.

But differences in values are an argument for improved dialogue with China, not against it. Nor should common values with the United States be used to support the case for unalloyed support for the US policies, where these policies are not in Australia’s overall interest. Political courage will be important here. That, too, is a value with which mainstream Australians like to identify.

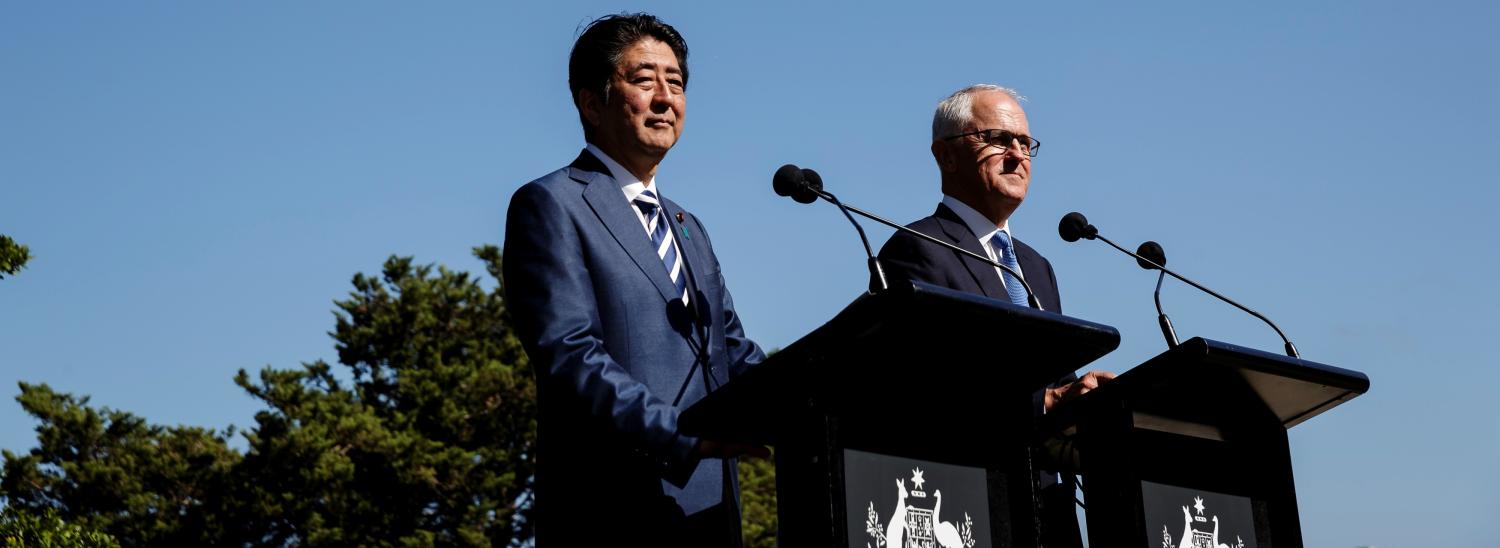

Photo: Flickr/jennofarc