Our end-of-year series as the Lowy Institute staff offer their favourite books, articles, films or TV programs for 2021. More recommendations and reflections. –Eds

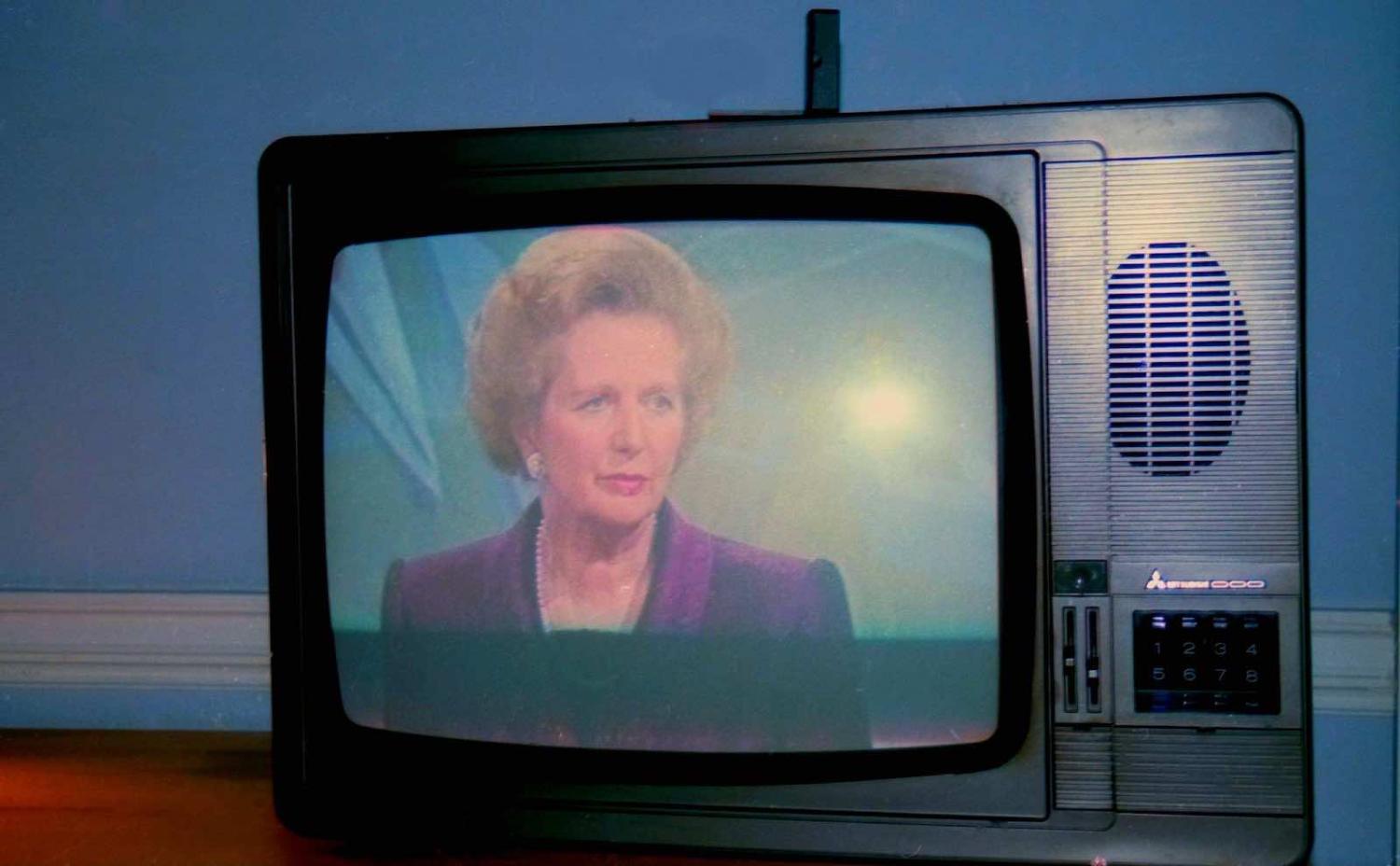

A reader got in touch this year to recommend Christian Caryl’s Strange Rebels. The book charts the remarkable convergence of leaders and events in 1979, which generated a profound legacy reaching to the present. Deng’s reforms in China, Khomeini’s revolution in Iran, Thatcher’s market upheaval in Britain, Pope John Paul II’s challenge to Communism from the Vatican, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan – all major developments from the year, all setting the shape of the decades to follow.

A reader got in touch this year to recommend Christian Caryl’s Strange Rebels. The book charts the remarkable convergence of leaders and events in 1979, which generated a profound legacy reaching to the present. Deng’s reforms in China, Khomeini’s revolution in Iran, Thatcher’s market upheaval in Britain, Pope John Paul II’s challenge to Communism from the Vatican, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan – all major developments from the year, all setting the shape of the decades to follow.

The reader was responding to my article on the importance of personality in world politics, asking whether the world would be quite the same without a Trump or a Xi? My reader took the question further in recommending Caryl’s book and wondered: would the Quad have happened without Abe or Modi?

The book was published in 2013 so doesn’t address such questions directly. But the message is clear about the need to account for the critical and enduring influence of individual personalities in world affairs.

The shape of the economy got me thinking about media coverage of the business community, where the influence of charismatic leaders is well understood.

Caryl was most instructive about the papal influence, a point I’d been sceptical about in the past. It was also a reminder of Britain’s tumultuous ride from a basket case economy in the early 1970s to the self-defeating obsession with Brexit.

But not to give away the ending, this factoid from Caryl struck me most. “The year 1979 marked the moment when income inequality in the United States began to increase for the first time since 1945 – the beginning of a trend that has continued to the present day.”

This point about the shape of the economy got me thinking about the media coverage of the business community, where the influence of charismatic leaders is well understood. It seems the rich personalities of an Elon Musk or Jeff Bezos can thank the 1970s for more than the establishment of technology such as email, bar codes and personal computers.

Main image via Flickr user R Barraez D´Lucca