While the West tends to dismiss North Korea as a rogue state or hermit kingdom, the reality is that North Korea is a nuclear power. That automatically boosts its position on the international stage. The Lowy Institute’s 2024 Asia Power Index (API), released this week, makes several mentions of North Korea, perhaps the most noteworthy of which is its classification of the country as a “middle power” alongside 15 others including South Korea, Russia and Japan.

The country poses a major security threat not just in the Asia-Pacific region, but globally, given its possession of missiles capable of reaching the continental United States.

Its formidable military capabilities are more than enough to warrant this status. Specifically, the API defines North Korea as “a misfit middle power” that “derives its power principally from its military resources and nuclear weapons capability”. While Pyongyang’s weak performance on the Index in terms of economic relationships, diplomatic and cultural influence, and other measures of power means it ranked towards the bottom of the middle power list, its place in this category is nonetheless warranted. The country poses a major security threat not just in the Asia-Pacific region, but globally, given its possession of missiles capable of reaching the continental United States.

Another notable finding from the Index relates to North Korea’s relationship with Russia. The API highlights Vladimir Putin’s 2024 visit to Pyongyang, describing it as “an effort to shore up Russian influence [rather] than an indicator of continued relevance”, arguing that Moscow’s resources remain focused on Europe, not Asia.

While the latter is true, Russia’s relationship with North Korea is increasingly affecting the war in Ukraine. North Korean weapons are reportedly being used by Russia in at least six regions of Ukraine, and Pyongyang continues to provide Moscow with artillery and weapons – some even manufactured this year – for use in the conflict.

Although the API report points out Russia’s loss of diplomatic influence over the past year, Russian diplomats remain in close contact with their North Korean counterparts. Multiple Russian delegations have visited North Korea in 2024, including military, law enforcement, and intelligence delegations, as well as youth groups and diplomats. Most recently, senior Russian security official Sergei Shoigu visited Pyongyang and met with Kim Jong-un on 13 September. So, while Russia may have alienated a great number of former partners, it is investing its diplomatic resources strategically, where it knows it can get beneficial returns.

China’s (ongoing) lack of regular political exchanges with long-time ally North Korea stands out, especially this year, which marks 75 years since the establishment of diplomatic ties.

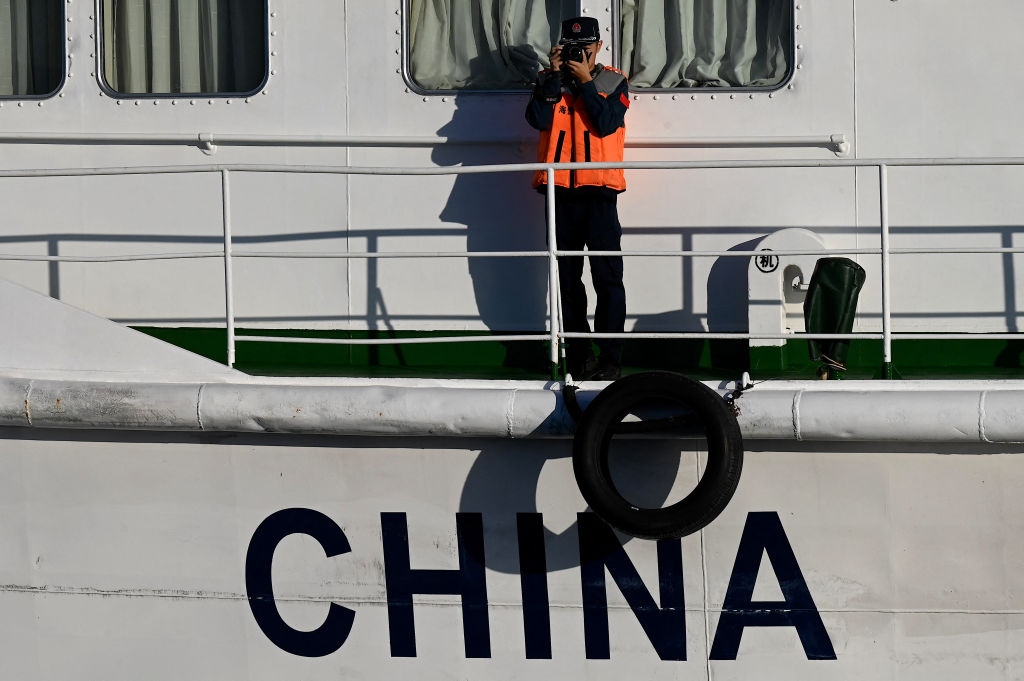

When it comes to China, the report points out the lack of high-level meetings between Beijing and Pyongyang, stating that in 2023, China “held a bilateral diplomatic dialogue at leader or foreign minister level with every other Asia Power Index participant except North Korea and Taiwan”. While the absence of diplomatic meetings with Taiwan is understandable, China’s (ongoing) lack of regular political exchanges with long-time ally North Korea stands out, especially this year, which marks 75 years since the establishment of diplomatic ties.

While the two governments agreed to celebrate the occasion through various exchanges and deepened cooperation, very little has come of it so far. Instead, President Xi has chosen to keep his distance, while Putin and Kim grow ever closer. Both Pyongyang and Beijing are likely making strategic decisions, with North Korea wanting more independence from China and the Chinese side not wanting to be paired with the likes of Russia and North Korea on the world stage.

Given China’s diplomatic and economic interests, Beijing is unlikely to join a military trilateral pact involving North Korea and Russia – at least for now. Nevertheless, Beijing will continue supporting Pyongyang to prevent a crisis along its border and to maintain stability, even as North Korea and Russia expand ties into potentially dangerous areas.