Two weeks of negotiations in Glasgow meant that COP26 resulted in a resolution – of sorts. Nations agreed to resume next year with stronger 2030 emissions reduction targets in a global bid to try to alleviate the worst consequences of the climate disaster. It wasn’t the achievement that was hoped for, but it was better than nothing, was the reasoned conclusion by many observers.

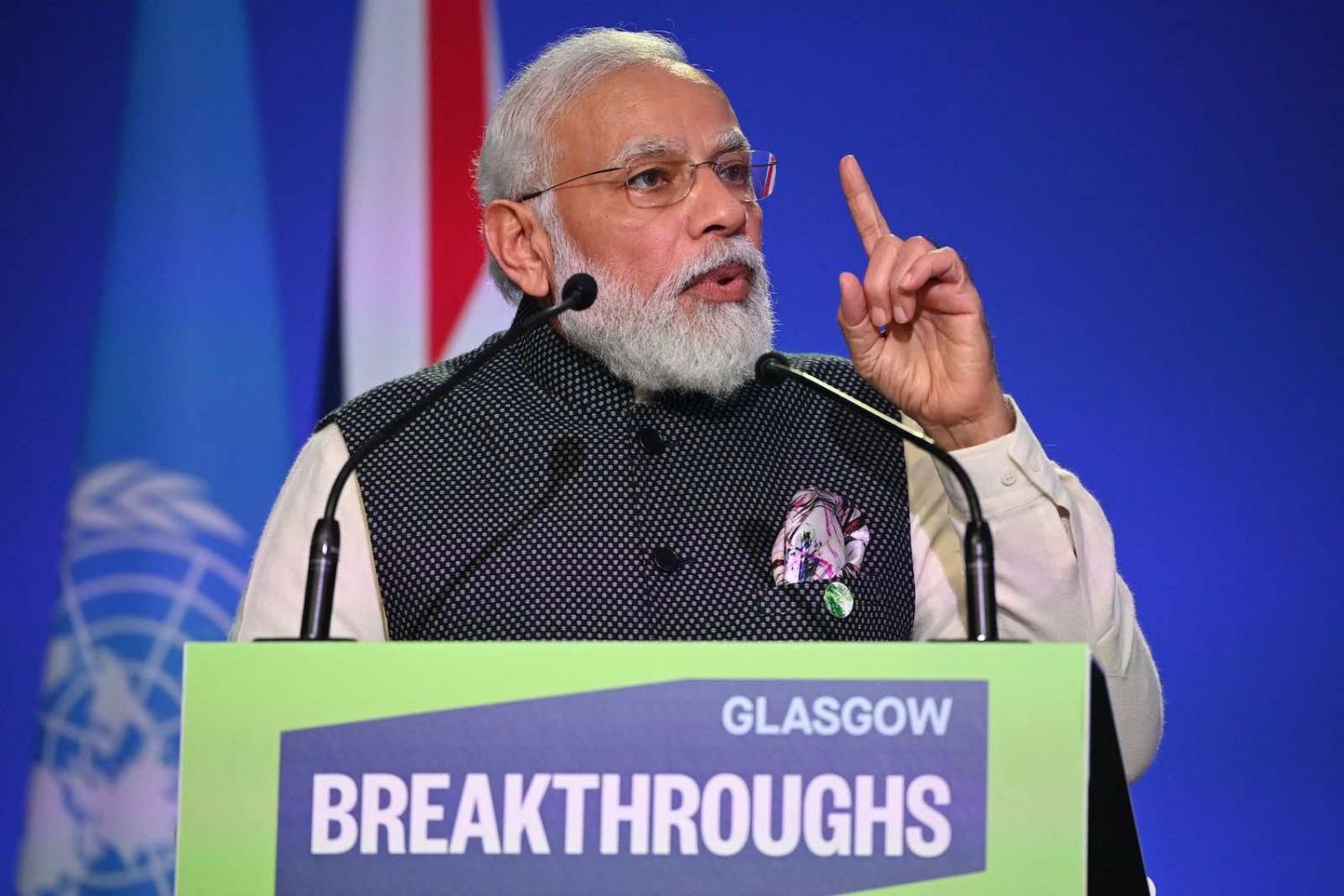

But one of the lasting impressions from the talks was to underscore the ongoing tensions of climate politics: a tug-of-war between the developed and developing worlds, with the latter helmed by China and India. The two Asian giants presented an eleventh-hour challenge by insisting that the language around coal power be watered down from “phase out” to “phase down”.

Many pointed out that India and other developing nations cannot be held to account when they contribute far less to global emissions.

In his closing remarks, COP26 President Alok Sharma voiced his disappointment and apologised to delegates “for the way this process has unfolded”. Britain’s Prime Minister Boris Johnson also weighed in, saying his delight at the summit’s progress was tinged with disappointment.

While many of us were willing to go there, that wasn’t true of everybody. Sadly that’s the nature of diplomacy … we cannot force sovereign nations to do what they do not wish to do.

So after two weeks of wrangling to little effect, ultimately the final analyses painted India and China, as the tacit leaders of the developing world, as those stymying efforts to help countries at far more risk avoid the lasting effects of climate change. Sharma later said India and China would have to “explain to climate-vulnerable countries why they did what they did”.

It’s pretty damning stuff, particularly when you add in headlines such as “Did India betray vulnerable nations?” (BBC) and “COP26 agrees new climate rules but India and China weaken coal pledge” (Financial Times). The optics have India and China painted as climate villains, intent on preserving their own economic growth at the throwaway expense of their more vulnerable neighbours.

But that’s the problem with the Google algorithm: it favours certain sources and media, so you’re not necessarily getting a well-rounded perspective of how the COP26 outcome was painted in other places.

In India, as in some corners of the Western media, there was disagreement with this view, with many pointing out that it and other developing nations cannot be held to account when they contribute far less to global emissions.

In particular, Indians are angry over the lack of the promised funding towards the developing world to help those countries adapt. One TV channel went so far as to label the summit a failure. “Why COP is a flop” said the newsreader. “After two weeks of hard-fought negotiations, the conference managed to achieve nothing of substance. The main point was to limit global temperatures,” she continued, leaning on the word “global”. “Which is why you need a fall guy. Fingers were pointed at India.”

On one hand, there are the usual Indian TV news histrionics at play, but the sentiment is not unreasonable. Why does the developed world continue to insist that India and China cycle harder towards achieving the goal of net zero when, per capita, developing countries use far less fossil fuel-based energy sources?

It’s a continuation of an argument that has plagued climate negotiations for years, even decades, pitting the developed world against the developing world. Wealthy countries want poorer countries to do more to curb emissions, while at the same time reneging on commitments to provide financial assistance as promised at a previous COP, 12 years ago, that they would contribute $100 billion per year to developing countries to help them become more ecologically sound – whether it be by redesigning cities or transitioning to cleaner energy sources.

But the amount donated has been far less than what was promised. The United States, which was expected to contribute almost half of that annual $100 billion, contributed somewhere between $6.6 billion and $11 billion per year. (Australia contributed less than $1 billion, while France was the largest donor.)

There was a new urgency surrounding Glasgow, but ultimately it was a continuation of the climate politics that have been ongoing for a couple of decades.

So what Indians are pointing out is that rich countries, which emit far greater emissions (such as Australia, which has the highest per capita coal emissions in the world, with each Australian emitting five times more carbon dioxide from coal than any other person in the world), seemingly want to force unrealistic goals on developing countries, and then fail to provide them with the resources they need to transition. And then point fingers at India and China for refusing to commit to end the use of coal.

Climate politics are nothing new. With the events of recent years – more frequent and more devastating natural disasters being experienced around the world, from bushfires to landslides to cyclones – there was a new urgency surrounding Glasgow, but ultimately it was a continuation of the climate politics that have been ongoing for a couple of decades.

For what it’s worth, the China and India effort to tweak “phase out” to “phase down” might have appeared as a power play and pure semantics, but there is more to it. China and India are already scaling up their use of renewables – for example, enormous solar parks in desert areas of Rajasthan – but recognise that it will take longer to shrink their dependence on coal, as well as oil and gas (the fossil fuels that aren’t mentioned as often as coal).

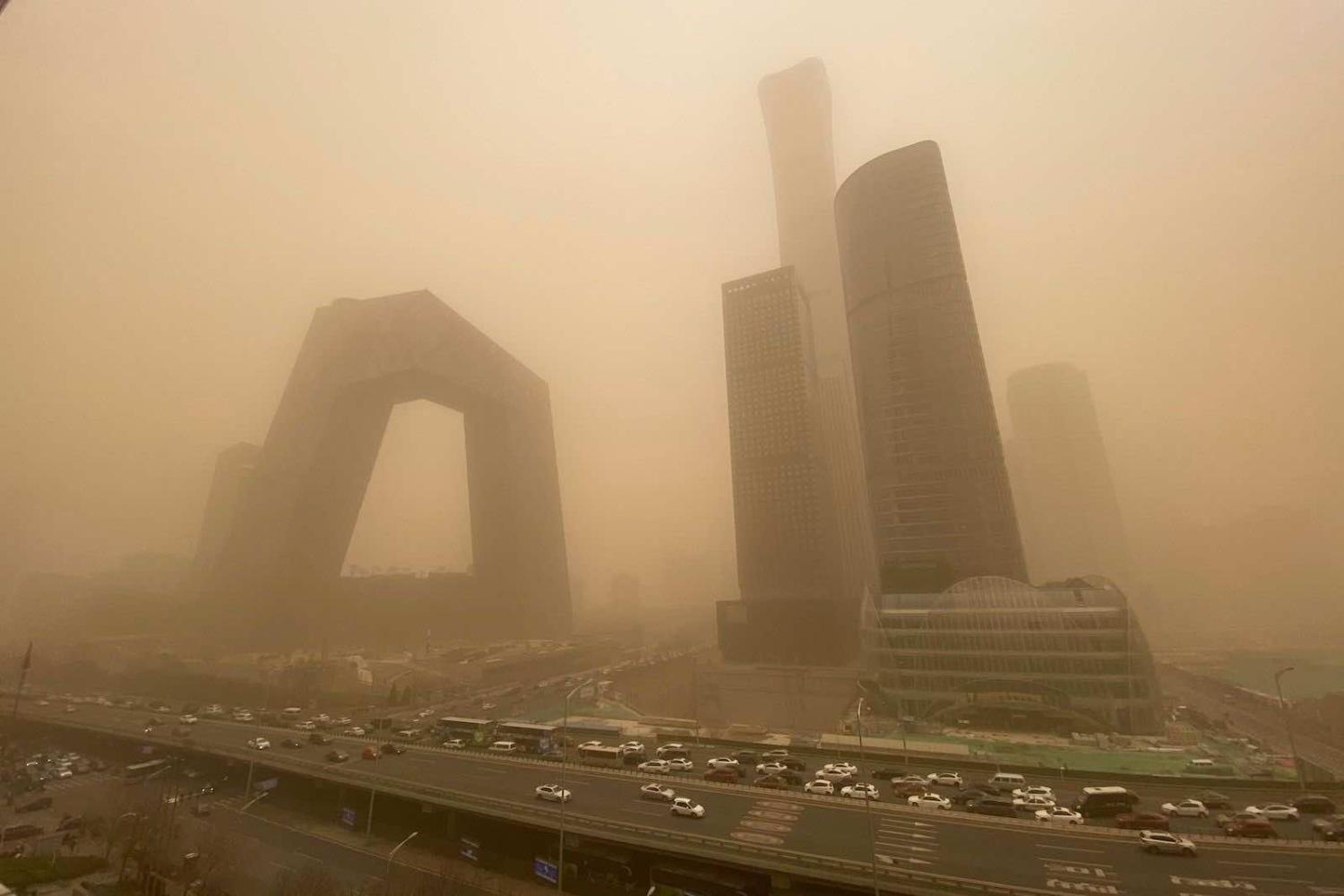

In an ironic coda to the end of the negotiations, India’s capital New Delhi went into a lockdown due to the city’s ongoing and worsening air pollution levels. Schools and colleges are shut indefinitely, and construction work has also been halted for at least the next few days. The smog is the result of a cocktail of factors: stubble burning in nearby Punjab and Haryana, the residue of Diwali firecrackers, and compounded by economic development, with extra cars, trucks, construction and factories. At the same time, winter is approaching, with the cold air sinking and trapping the pollution.

So, paradoxically, as India agitated for greater leniency on net zero, its own citizens were choking on smog. It’s a reminder of how diplomatic self-interest isn’t always in the best interest.