Stephen Blank's very generous comments on A Wary Embrace arrived too late to cover in my response to the original contributions in The Interpreter debate. But he brings up a number of additional points that deserve a reply.

The nature of the China-Russia relationship

Blank somewhat mischaracterises my summation of the Sino-Russian partnership as 'a tactical rather than principled relationship'. In my earlier book, Axis of Convenience: Moscow, Beijing, and the New Geopolitics, I wrote (p.54) of an interaction that combined 'tactical expediency with strategic calculus and long views' – a judgement I reaffirm in A Wary Embrace (p.108). The point is that this is a complex relationship that cannot be encapsulated by standard formulations such as 'strategic partnership' and 'authoritarian entente'. Instead, it is a 'relationship of strategic convenience' that has major achievements to its credit, but also labors against significant constraints (p.139).

The durability of the partnership

Blank poses the critical question of how the Sino-Russian partnership has survived the growing asymmetry of capabilities between the two sides. A Wary Embrace directly addresses this issue. It notes that 'both sides understand that they are better off emphasising the positives and … underplaying their differences' (p.109). Despite overblown claims of strategic and normative convergence, and the limitations of the relationship, 'the balance sheet is largely positive, and Beijing and Moscow are committed to making things last' (p.130).

Moscow's concerns about the strategic challenge posed by China are real, but also long-term and often nebulous. As such, they have been pushed into the background by more urgent priorities. By contrast, the Kremlin sees the US as the 'first enemy' – a perception that has barely changed with Donald Trump in the White House.

For its part, Beijing is committed to nursing a relationship that favours it in key respects. It understands there is far more to gain by accommodating Russian sensitivities than by adopting an overtly competitive approach. The painful experience of Western policy-makers with Moscow has shown that 'even a "weak" Russia has the capacity to cause plenty of trouble' (p.137).

The Sino-Russian partnership works as well as it does because both sides see it as beneficial. They also recognise that the alternative to cooperation is fraught with risk and anxiety. However, Beijing and Moscow have few illusions about each other, for all their flowery rhetoric. This is a partnership driven not by normative convergence – the 'authoritarian international' that Blank and others speak of – but by cold-blooded strategic calculus and concrete interests.

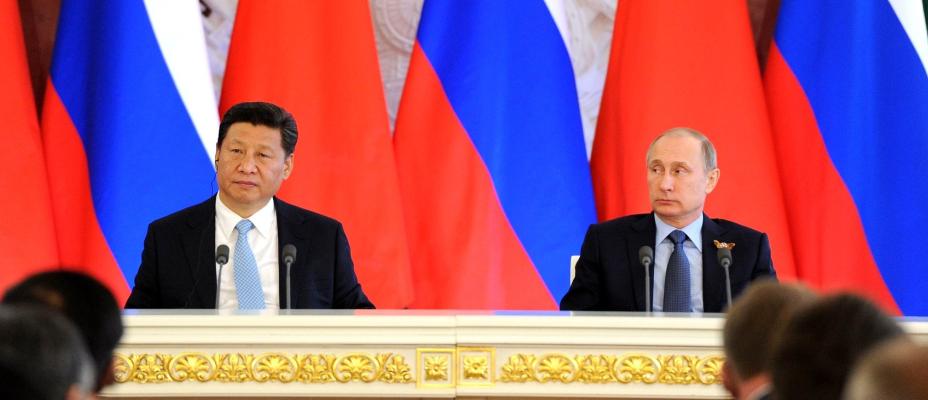

The Xi-Putin dynamic

It has become de rigueur to highlight the special relationship between Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin. This is closer and warmer than most interactions between world leaders, although Chinese scholars tend to underplay this aspect compared to their Russian and Western counterparts. We should not, however, overestimate the personal factor. Sino-Russian partnership was already on a steady upward trajectory during the era of Xi's predecessor, Hu Jintao (2004-12), with whom Putin had no particular rapport. Conversely, the cordial dynamic between George W Bush (2001-09) and Putin was unable to check the sharp deterioration of US-Russia relations.

A good rapport at the highest level may facilitate a relationship, but only very rarely (if at all) does it alter the fundamentals. The China-Russia relationship works not so much because Xi and Putin like each other, although that clearly helps, but because cooperation is seen to serve the interests of both parties.

Blank reiterates the popular, but implausible, claim that Xi has been 'influenced by Putin's example to establish himself as the strongest ruler in China since Mao'. In fact, there are far more compelling reasons why Xi has systematically consolidated his personal power since becoming President in 2012: a strong individual sense of mission; a long-standing commitment to national 'greatness' (exemplified by the slogan 'China Dream'); a reformist zeal notably absent in Putin's Russia; and several thousand years of Chinese authoritarian tradition.

The US factor

Blank suggests that I have given too much emphasis to the role of the US in influencing the course of the Sino-Russian relationship. Yet he also argues that their 'ideological, political and institutional partnership' is a defensive response not only to US power, but also to 'any form of liberalism'. It is hard to see this comment as anything other than de facto acknowledgment that US soft and hard power has been the main driver of Sino-Russian partnership. While some observers might be inclined to raise a shout for European liberalism, the reality is that Kremlin narratives on the conflict in Ukraine, NATO enlargement, and Euro-Atlantic security have consistently portrayed the Europeans as being in thrall to Washington, with little independent voice of their own.

Domestic influences

Some Western commentators assume that one big authoritarian regime thinks and behaves much like another. Blank largely avoids this trap, highlighting a crucial distinction between Chinese and Russian governance – 'whereas Chinese politicians may be corrupt, in Russia corruption is the system'. He also suggests that the leadership in Beijing is more committed to privileging the national interest over private interests. It is difficult, however, to square such views with his claim that Beijing and Moscow have achieved an 'ideological consensus of the "authoritarian international"'. For while they agree on the primacy of sovereignty and national prerogatives, so too do Washington and London – as we have seen very clearly in recent months.

More generally, Blank believes that I neglect the domestic dimension of the relationship. But is that really so? I note Moscow's historical anxiety about the vulnerability of the Russian Far East (p.25), and the catalytic effect on cooperation of the anti-Putin protests of 2011-12 and the accession of Xi (pp.13-14). I refer to the potentially game-changing consequences of rising nationalism, regime instability, and economic conditions (pp.131-32). And I conclude that the future of the relationship 'may depend less on the international context … than on what happens inside China and Russia' (p.139).

A compliant Russia

Blank asserts that Russia has made major concessions to China in several areas – the Arctic, weapons sales, relations with other East Asian countries, and in Southeast Asia. In my view, he overestimates the significance of these concessions. For example, Russia may have allowed China to acquire observer status in the Arctic Council, but this is hardly a game-changer. As a mere observer, China has no voting rights, and was only admitted as part of a larger intake of observer states, along with Japan, South Korea, India, Singapore, and Italy. There has been zero movement in the core Russian position that only Arctic littoral states may decide the future of the region.

In A Wary Embrace, I acknowledge that the 'idea that Russia would sell its most advanced weaponry to China was almost inconceivable only a few years ago' (p.35). But it is a stretch to claim, as Blank does, that this shift is due to the narrowing of Russia's options. One of the features of recent Russian arms sales to Asia is their growing diversification. Moscow not only continues to sell large quantities of weapons to traditional customers, such as India and Vietnam, but it is also expanding into new markets in Southeast Asia. In this area at least it is operating from a position of strength, not weakness.

Blank rightly notes the growing Sinocentrism of Russian policy toward Asia. Yet it is questionable whether this has much, if anything, to do with Chinese pressure. True, on the Korean peninsula 'Moscow is virtually out of the running as a serious interlocutor in the current crisis'. But then again was it ever in the running? Certainly not for some decades. Similarly, Putin's refusal to make serious concessions to Japan is born not of a feeling of strategic dependence on China, but the conviction that ceding territory to Japan is incompatible with Russia's self-image as a global great power.

Outlook

In considering the longer-term future of the relationship, it would be wise to keep an open mind, especially given the ongoing chaos in US decision-making and a volatile international environment. We should be wary of assuming either that China and Russia are growing seamlessly into an authoritarian alliance or, on the contrary, are destined for confrontation. Nothing is inevitable, and there is considerable scope for strategic shocks to alter the 'normal' course of events (p.118). Amidst all this uncertainty, however, one thing is clear. China and Russia still have much to do if they are to change the basis of their 'strategic partnership' from today's pragmatic self-interest to a deeper and more lasting convergence.