It is tempting to see doping controversies at the Olympics as a challenge unique to sports governance. After all, few workplaces or life moments require performance enhancing drug testing.

Yet the failures of the Olympics – opaqueness, the inability to adapt to new powerful biological technologies, mistrust between China and the United States, and a lack of resources in the developing world – are repeated across most elements of global biological technology governance (bio governance for short).

Right now, global bio governance has the worst of both worlds. Risk is not being effectively managed. And the benefits of new biological technologies are being held back.

For example, much of the human DNA collected, which could contribute to significant medical breakthroughs, remains siloed away from major databases. Even population-wide genetic variance data (not individual level genomes) is often inaccessible to global researchers. Much of the available data is for people of white-European ancestry, meaning that common disease-causing genetic variations are more likely to be found and treated in white people.

We are not doing better on the risks.

If a pathogen with Covid’s risk profile emerged in China tomorrow, the world would unlikely have a better response.

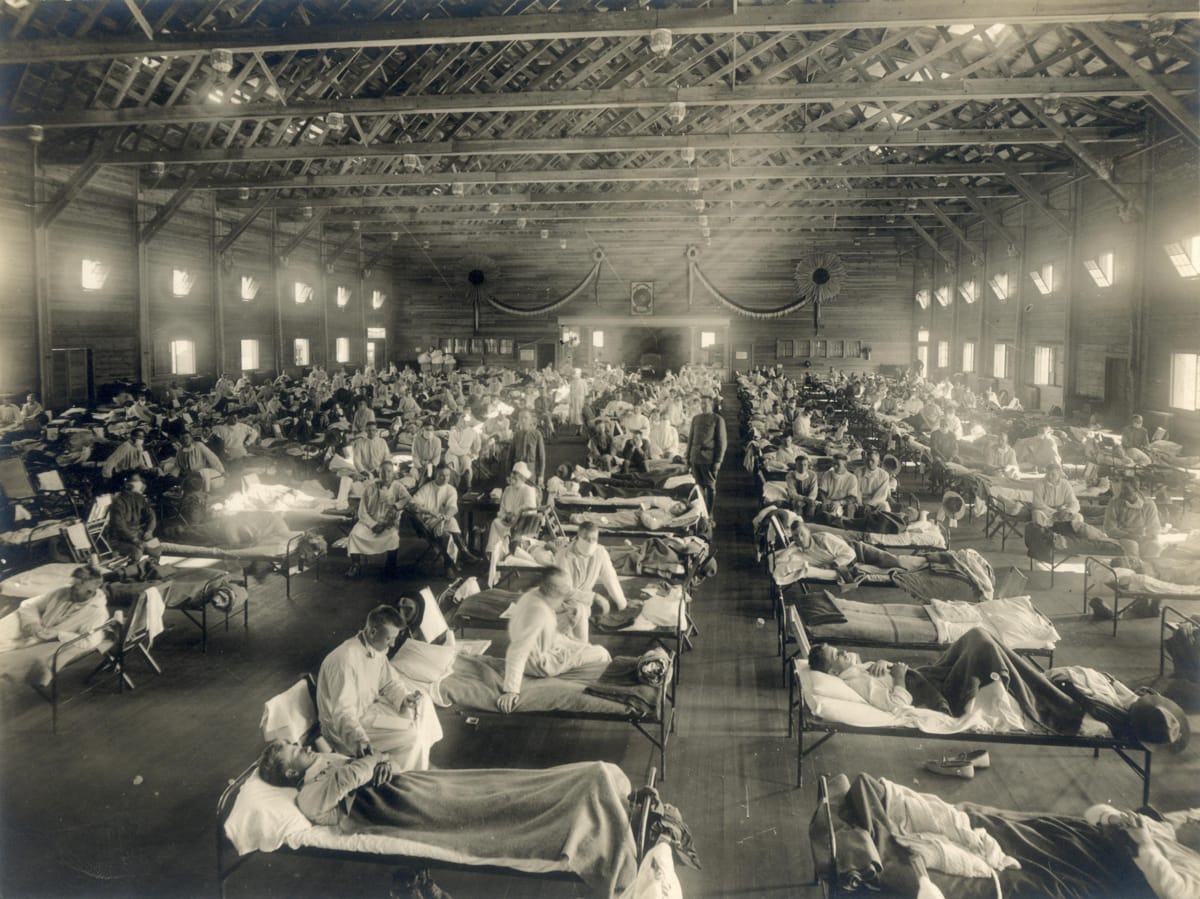

If we take public health, for example, the world (and the world’s leading virologists) still do not know if Covid-19 leaked from the lab or jumped species in nature. We do not know because of Chinese government secrecy which, at times, was aided by the World Health Organisation. Excess deaths since the beginning of the pandemic are 27 million. Covid continues to kill millions of people a year.

Many steps of the Covid response have been stalked by governance failures. The US government ran disinformation campaigns against effective Chinese vaccines often when there was no alterative due to shortages. The Chinese government lied about Western-developed vaccines to its own people. In the early days of the pandemic, the Chinese government hid data, genome sequences and medical outcomes of the virus that, if transmitted to other governments, would have saved lives.

These are not well-meaning missteps in the face of pandemic uncertainty. They are lies for geopolitical goals. If a pathogen with Covid’s risk profile emerged in China tomorrow, the world would unlikely have a better response.

Global biosecurity governance is also woefully underprepared for new DNA synthesis capabilities. Both the genome sequences of pandemic viruses and step-by-step protocols to make infectious samples from synthetic DNA are freely available online.

In May, an MIT team, posing as non-scientists (because MIT is a trusted purchaser and it would skew results), ordered fragments of the Spanish flu from 38 DNA suppliers; 36 out of 38 providers sent them the fragments. There are multilateral and unilateral governance mechanisms to stop this from happening. They do not work.

Environmental bio governance has not fared much better. The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) is meant to preserve species diversity. Since its inception in 1992, species loss has continued unabated. Research by our team at the Australian National University and InKlude Labs in India shows developing countries do not have the resources to deliver CBD requirements. The United States has not ratified the CBD.

There is no global plant and microbial gene-editing governance mechanism. It is left to individual countries. Many governments restrict the planting of genetically modified (GM) crops. But enforcement remains patchy. Indian and Chinese farmers illegally planted GM crops because of higher yields and greater pest resistance. So, with climate change bearing down on farmers and consumers, countries are approving more and more GM crops.

While these examples cover a wide range of bio applications (and even that is far from complete), it is a handful of underlying technologies that are driving the biggest changes. This includes cheap collection, storage and manipulation of genetic data (particularly using AI), the ability to synthesise large volumes of DNA, and the ability to edit the DNA of most types of organisms.

So, we need to find a way to better govern these technologies and their applications.

Despite the long list of global agreements, meaningful government cooperation involving the United States and China will likely remain out of reach. So, other countries in the region need to find a way forward to share benefits and manage the risk. And do so in a way that is actually feasible for resource-restrained countries.

Our ANU-InKlude Labs team has made a first step in this direction. We have published the new Ethical Frameworks for Deployment of Synthetic Biology in the Indo-Pacific. It offers risk-tiered approaches to data sharing and gene editing. It also explores how poorer countries can disproportionality benefit from the deployment of this technology.

We will be pursuing workshops over the next few months to build regional linkages on this technology.

Reactions to biological technologies, such as gene editing, will be deeply personal and countries may not agree on approaches. But we need to open these dialogues now, so that we understand each other’s risk appetite, and to respond when geopolitics gets in the way and threatens the lives of people in our region.

At the next Olympics, drug testing will remain a source of controversy, but hopefully then we can say that it is unique to sport and that our global bio governance structures are in better order.