Book Review: Homelands: A Personal History of Europe by Timothy Garton Ash (Bodley Head, 2023)

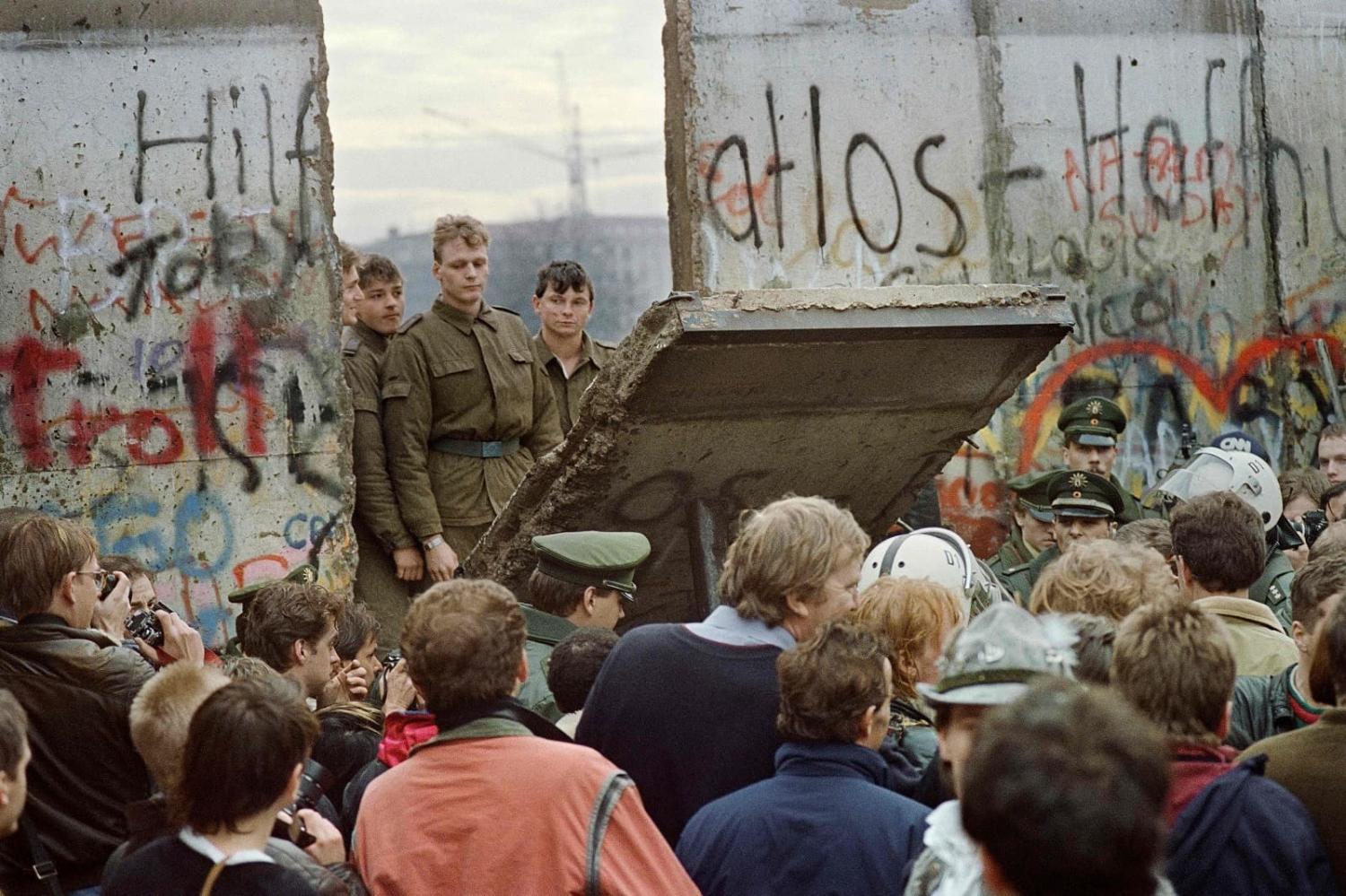

A decade or so ago, Timothy Garton Ash might well have envisaged a memoir-cum-analysis of modern Europe as a celebration. After all, the Berlin Wall had fallen, the Balkan wars had ended, the Soviet Union had collapsed, NATO and the EU were expanding, and the engine of capitalism was producing increased prosperity. Now, instead of a love letter, Garton Ash has penned an elegy.

A decade or so ago, Timothy Garton Ash might well have envisaged a memoir-cum-analysis of modern Europe as a celebration. After all, the Berlin Wall had fallen, the Balkan wars had ended, the Soviet Union had collapsed, NATO and the EU were expanding, and the engine of capitalism was producing increased prosperity. Now, instead of a love letter, Garton Ash has penned an elegy.

Written after Brexit, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the rise of hard-edged populism, an immigration crisis, fumbled handling of Covid, mediocre leadership and scepticism throughout Europe about the European institutions, Homelands is tinged with rueful, sometimes bitter judgments.

Garton Ash is a sophisticated and intelligent observer, working for more than a generation now “with pen and voice” to make sense of Europe’s “kaleidotapestry”. That term is Garton Ash’s coinage, one he preferred to millefeuille or patchwork quilt. Insisting that he makes “no claims to be comprehensive, impartial or objective”, Garton Ash seasons his “history illuminated by memoir” with rich personal experience as well as a beguilingly eclectic cast of fellow Europeans. The book serves as a tribute to “freedom and Europe – the two political causes closest to my heart”.

Other analysts might argue that, for Europe, the rot set in decades ago. As Garton Ash suggests, the fall of the Berlin Wall might have comprised “an exceptional, once-in-a-million piece of historical luck”. Europe’s ebullient optimism around 1989 needed, however, to be tempered by memories of the mechanistic over-reach in the EU’s Maastricht Treaty, Europeans’ callous decision not to stop the three-year siege of Sarajevo, French and Dutch rejection of the European constitution or emerging indifference to growing inequality. I recall a senior French official describing admission of Greece to the EU as “a generous mistake”. As for Bulgaria and Romania …?

While Garton Ash certainly addresses those early symptoms of decay, he is more concerned about the recent downwards slide. That seems right. Europe’s once prodigious assets seem to be waning, while its problems seem both systemic and intractable. A leader able to address economic inequality, political populism, social discontent, uncontrolled immigration, an ageing population, energy transition, welfare entitlements and the war in Ukraine would be a remarkable, welcome novelty.

In the meantime, readers may rely on Garton Ash for judiciously civil, liberal commentary, often embellished with wry wit. Garton Ash, for instance, describes the early tactics of socialist group Solidarity as “the political equivalent of a judo throw”. He notes whimsically that “Canada would be a perfect EU member”. Europe’s neighbours now possess “the weapon of mass migration”. Garton Ash also scrapes away the “posthumous beatification” of former Czech Republic president Václav Havel to provide a more subtle, nuanced portrait of a friend.

Few possible conjunctures could force a return to the bad old days, “when Siberia began at Checkpoint Charlie”. Nonetheless, the clout of Europeans believing in Churchill’s “bright, sunlit uplands” has slumped, perhaps beyond repair. Europe whole and free, wider and deeper, might just be a mirage.