It is near impossible to find any mention of the Chinese chip hacking story in Bloomberg Businessweek that does not use the words “bombshell” or “explosive” to describe the piece. These descriptions have become cliché. But the cliché is fitting because even if the story unravels amid vehement denials, its impact will be far-reaching, no matter what we learn about what actually occurred.

Immediately after the story broke, debate erupted in the US information security community over what exactly happened. Some argued that Bloomberg’s story appeared deeply sourced, and that the companies implicated have every incentive to stridently deny allegations that could cripple their reputation and upend their supply chains.

It does not even matter whether the story is accurate or not because the damage has already been done.

Yet, the denials of the companies did not appear written by lawyers or public relations professionals, but contained comprehensive, detailed counter arguments. As David Vladeck, Georgetown professor and former head of the US Federal Trade Commission’s (FTC’s) Bureau of Consumer Protection, told Axios, “the companies [would] risk enforcement by the FTC for engaging in a deceptive act that is likely to harm consumers”.

The Department of Homeland Security and the British National Cybersecurity Centre both issued statements of support backing the companies’ position.

The problem is that the material needed for information security professionals to verify the Bloomberg story is not likely to be issued to the public any time soon. It would be helpful, for example, to know the results of a third-party security firm or an investigation by the US Computer Emergency Readiness Team (US-CERT). Have incident response and forensics been completed? Perhaps there will be a congressional hearing at some point, but until then data needed for the public to understand the full picture will remain classified.

But it does not even matter whether the story is accurate or not (the answer is probably somewhere in between) because the damage has already been done.

The story broke the same day as Vice President Pence’s “bombshell” speech at the Hudson Institute in Washington DC, in which he made clear that the Trump administration plans to sever economic and industrial ties with China. Conspiracy theorists will argue that the Bloomberg reporters got played by operatives in the Trump administration looking to accelerate this so-called “de-coupling” or “de-linking” with China. Yet, pulling off that kind of stunt would be exceedingly difficult given the reality of the lumbering size of the US bureaucracy.

Even if the timing was just a lucky coincidence for the Trump administration, Bloomberg’s story accelerated a longstanding push to cut out China from US supply chains. It fits into a narrative building for a long time about the existential threat to US national security posed by Chinese telecom companies like Huawei and ZTE.

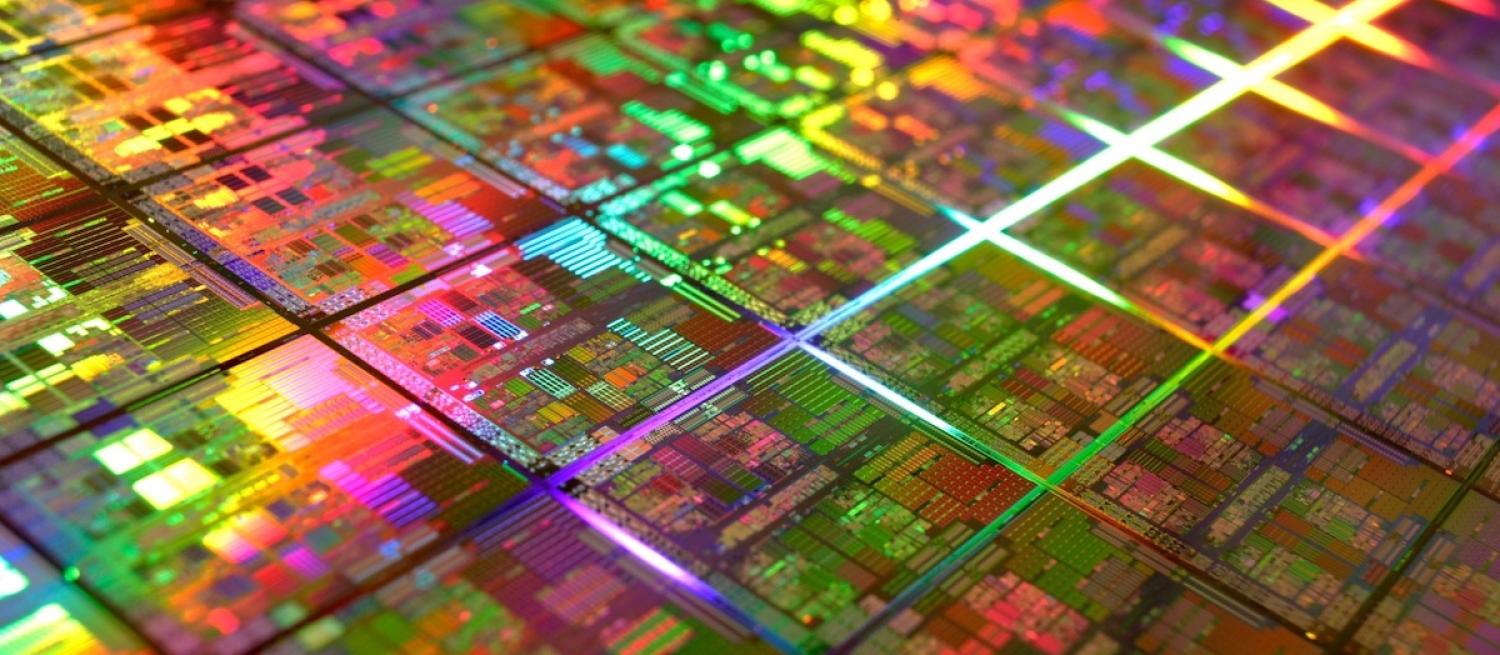

As Jorge Guajardo (former ambassador from Mexico to China) explained in a series of tweets, “it puts a nail in the coffin of China’s aspirations to develop a microchip industry. There will be no market for them, and China’s is not big enough”. He went on to explain how “it gives the United States the upper hand in convincing allies and non-allies around the world to be weary of Huawei and ZTE. It comes at a key moment when countries are deciding how to upgrade to 5G. This may be a lethal blow for Huawei. No one will trust them.” Huawei has already been banned from participating in Australia’s 5G network.

For US businesses, the story leads to a fundamental shift in thinking about the trade-offs of global supply chains. There will be less tolerance for the risks that come with efficiency and cost savings, and more need for transparency and control in sourcing decisions. Industry and national security experts have been concerned for years about the risks of information and communications technology (ICT) manufactured in China, but now there is a case study (even a flawed one). Moreover, even if the Bloomberg story falls apart, the approach it describes is consistent with public statements made by the Chinese military for a long time.

The question then becomes what is even possible when it comes to so-called “de-coupling” with China. Paul Mozur of the New York Times points out, “It won’t be easy. They are working against 40 years of economic integration and a tremendously complex web of big and small companies.” China is a massive market and production site for US companies, making packing up and leaving a complex and costly undertaking, if even an option at all.

In just one week following Pence’s speech and the Bloomberg story, we saw an almost daily barrage of negative China news. A White House report cited Chinese theft of dual-use technology as a top threat facing the US defence industry. The Department of Justice announced the arrest of a Chinese intelligence officer for espionage targeting US aviation technology.

What is clear is that the US and China are engaged in what is shaping up to be a deepening conflict over technology and cyberspace. The contours of this conflict extend well beyond this one story. There are no offramps in sight.